A history of council homes in Oxford

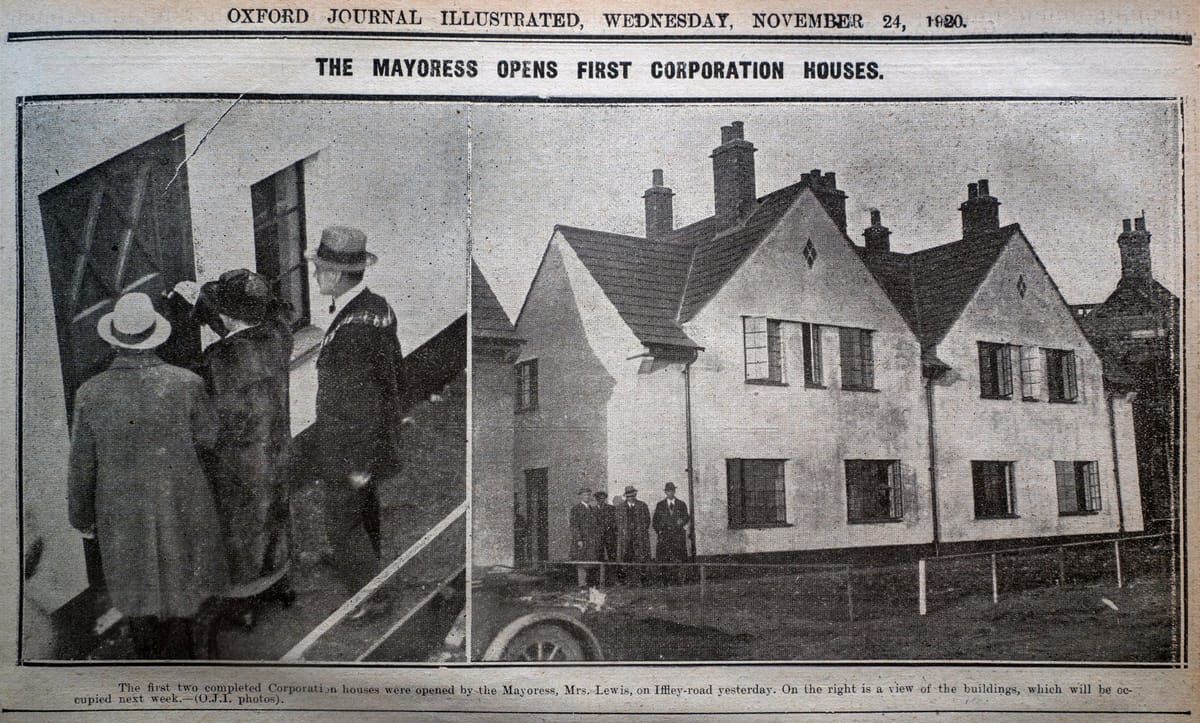

This Saturday, 23 November, marks the anniversary of the first completed council houses in Oxford. They were opened in 1920 by mayoress Florence Lewis, wife of mayor Edmund Lewis.

The two houses still stand on the corner of Iffley Road and Addison Crescent. To mark the date, we take a look at the history of council housing in Oxford – from the very first two right up to the present day, with the twists and turns of legislation that accompany this city's long fight to house its workers.

Homes fit for heroes

The opening of these first ‘corporation houses’ in Oxford was a milestone. Addison Crescent was named after Liberal, later Labour, housing minister Viscount Dr Christopher Addison – architect of the Housing, Town Planning Act 1919. The Act, passed to fulfil Lloyd George’s pledge of “homes fit for heroes”, marked the beginning of council housing nationally.

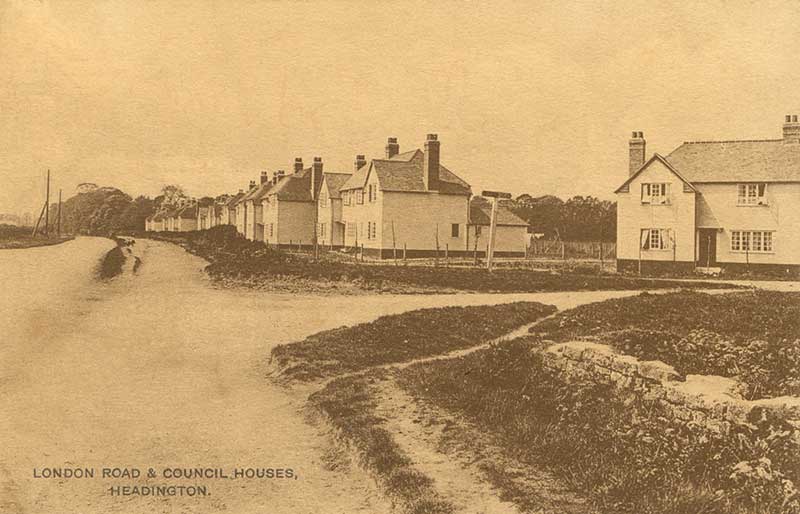

While the Addison Crescent homes were lauded as the first in Oxford, they were not in fact the first council houses in what is now the city of Oxford. In July 1920, Headington Rural District Council beat Oxford to the line by four months and completed its first 24 council houses. However, Headington did not formally become part of Oxford until the area east of Gipsy Lane was incorporated into the city in 1928, with the rest of Headington joining a year later.

A total of 215 ‘Addison Act’ council homes were built by what was then the county borough of Oxford. These first estates were on Cowley Road and Iffley Road, then on the outskirts of the city. They featured homes with steeply gabled roofs and Arts & Crafts detailing.

A city built on wheels

Between the wars, Oxford was one of the fastest growing industrial cities in Britain. In 1921, the city’s population was around 57,000. By 1941 it had almost doubled to 107,000. This was the result of a rapid expansion in the motor industry and associated trades, with Morris Motors and Pressed Steel alone employing around 10,000 workers.

To help meet the needs of a growing city, the building of council homes accelerated through the 1920s. Between 1923 and 1930, 1,647 new council homes were built. These included homes in Cowley, Headington, Morrell Avenue, Freelands and Gipsy Lane.

Over the following decade, hundreds more were built on new estates fringing the city, such as Cutteslowe, New Marston, Wolvercote, Risinghurst and Sandhills. They provided new homes for people rehoused from city centre slums, who now had their own gardens and an indoor bathroom for the first time. These also included the first 449 council homes on Rose Hill, built in two phases between 1933 and 1939.

Cutteslowe Walls (Oxford History Centre)

Building new council homes was not without controversy, most notably in the shape of the infamous two-metre high Cutteslowe Walls – built in 1934 by a private developer to separate their houses from the adjoining council estate. A potent symbol of class division, the walls forced council tenants into a 600-metre detour to reach Banbury Road and sparked widespread uproar.

Although Oxford City Council unilaterally bulldozed the walls in June 1938, the High Court ordered their reinstatement. The Cutteslowe Walls were not finally demolished until March 1959, after the council paid £1,000 to buy the land they were built on. As our long read explains, you can still spot the dividing line today.

At the end of the Second World War, the housing waiting list stood at 5,000. The continued expansion of Morris Motors and a post-war baby boom made the need for new council homes more urgent. A shortage of available land – worsened by the adoption of the first green belt outside London in 1956 – meant post-war council housing was concentrated on new estates south and south-east of the city.

From farms and army camps to new communities

In 1937, there were just 54 council homes in the former hamlet of Barton – once the home of a Roman villa, and on the course of a Roman road between Dorchester on Thames and Alchester.

In the 1930s the council purchased land from Magdalen College. Building resumed in 1946 both here and in Rose Hill, earmarked for 690 council homes. By 1950, Barton had 1,000, rising to 1,600 by 1977.

Other big postwar council estates included Northway (570 homes from 1951), Wood Farm (510 homes from 1953), Horspath Road (310 homes from 1958) and Slade Park, built on the site of a former Army training centre (320 homes from 1974). The largest was Blackbird Leys, originally home to many workers in the Morris car plant. The area was originally called Blackford Leys; blackford after the dark-coloured ford which crossed the southern branch of Northfield Brook, and the Middle English leys meaning pasture or meadow.

Planning permission for 2,800 council homes in Blackbird Leys was granted in 1953, with the first residents moving into their new homes in 1958. Although Oxford had largely avoided the use of high-rises which were becoming popular at the time, Blackbird Leys included the city’s first two tower blocks in Evenlode and Windrush towers. (We previously looked at why Oxford's skyline is largely protected from high rise buildings.)

Three further high-rise blocks followed in the shape of Plowman, Foresters and Hockmore towers, between them providing 348 council flats by the end of the 1960s. Work on the second phase of Blackbird Leys began in 1964 and continued into the 1970s.

Right to Buy

As the 1980s dawned, Oxford had more than 10,000 council homes. All this was to change.

The Housing Act 1980, and its flagship Right to Buy policy, enacted a pledge in Margaret Thatcher’s winning 1979 Conservative Party manifesto. It gave council tenants the legal right to buy their homes at a large discount, and was wildly popular across England.

Over the next 40 years, the Right to Buy meant 4000 happy tenants bought the council homes they'd lived in for years and fulfilled their dream of home ownership. But it also meant the loss of more than 4,000 council homes in Oxford, 40% of the stock. Councils were not permitted to build new homes from the proceeds of these sales, and by the mid-1990s construction of new council homes ground to a virtual halt across the country. In Oxford, the number of households living in a council home fell from nearly a third (29%) in 1981 to a fifth (21%) in 2011. Meanwhile, the city continued to grow. The hospitals grew; the universities grew; the knowledge economy grew. And all these people needed somewhere to live.

The story of council housing could have ended there, but Oxford’s housing crisis demanded action. In 2016, Oxford City Council set up its housing company, Oxford City Housing Ltd (now renamed OX Place), to build new council and other affordable homes.

OX Place’s stated aim is to build more than 2,000 new homes for rent and sale in and around Oxford by the end of this decade. These, they say, will include a new generation of more than 1,100 council homes providing “genuinely affordable homes let at social rent” – typically around 40% of the rent a private landlord would charge for the same home.

OX Place completed its first two council homes in Kidlington in March 2021, with further developments following in Marston, Barton and Rose Hill the same year. Work is ongoing at Marston Paddock to deliver 40 affordable homes. It will be called Fishers Vale and include 26 houses and 14 flats, built to blend in with the adjacent Marston Conservation Area, with expected completion in Autumn 2025 as 100% council and shared ownership homes.

OX Place development at Marston Paddock (Oxford City Council)

Finding space in a crowded city

Oxford has few suitable development sites left within its administrative boundaries and many of these would not be considered viable by purely commercial builders. Yet the city needs homes.

So the challenge for OX Place is to eke out small infill sites and previously developed land using innovative construction methods, even if some build sites cause raised eyebrows. (Our Housing Week series explored the challenges of building within a medieval city encircled by rivers and university land.)

Barton Park: the beginning of a virtuous circle?

The development at Barton Park is significant in itself as Oxford’s largest housing build since the 1970s. But equally important is how it has been financed – perhaps setting out a way forward for similar developments.

When work to build the first homes at Barton Park started in 2015, government finance restrictions meant councils could not use their housing revenue accounts to fund the building of affordable council homes. Instead, Oxford City Council used low-cost borrowing to finance Barton Park’s affordable homes from its general fund – but this meant they could not be council housing.

Then, in 2018, borrowing restrictions were lifted. In December 2024, the council will purchase 168 affordable homes from its subsidiary OX Place at a cost of £33.4 million, bringing all these homes on to the council register. This, in turn, allows OX Place to repay loans, and funds it to continue building affordable council and shared ownership homes.

And now?

Right to Buy still exists. The council continues to build, and to permit building, because Oxford needs homes: owned homes, tenanted homes, mortgaged homes, social homes. As it builds, so tenants still have rights to purchase… and the cycle continues.

At least for now. The new Labour government is indicating moves to restrict Thatcher’s Right to Buy. The BBC’s description could have been written with Oxford in mind:

[Deputy Prime Minister Angela] Rayner has said recently she may impose restrictions so that people who move into newly built council houses will not be able to buy them in the future. It is a decision that is likely to be welcomed by Labour politicians in regions where the need for social housing is arguably as great as ever, but the amount of it available is very low.

Much of Addison Crescent was bought by tenants under the Right to Buy. These are now private homes. But just one mile away, over Donnington Bridge, the council and OX Place are consulting on 200 homes in the bucolically named “Redbridge Paddock”. Might these stay council-owned in perpetuity?

Over 100 years have passed since the first occupiers moved into Addison Crescent. But one thing has not changed. Oxford urgently, still, needs more homes.

Thank you to Oxford City Council for their assistance with this piece. We are all the Clarion.

Further reading

- Municipal Dreams: Posts on early council housing in Oxford and on the construction of Blackbird Leys.

- Housing Week: Our series of articles on the challenges of building in Oxford.

- Oxford Civic Society’s 2025 programme of talks on housing in the city.