Abingdon Reservoir: is there an alternative?

Few projects in Oxfordshire have excited as many column inches as Thames Water’s proposed Abingdon Reservoir. Is it a simple NIMBY battle – or are the issues more complicated than that? Andy Cooke, local councillor and water champion for Vale of White Horse District Council, thinks it deserves more thought in this guest article for the Clarion, the first in a short series.

There’s been a lot of sound and fury over the Abingdon mega-reservoir proposal, or “South East Strategic Reservoir Option” (aka SESRO) as it’s become known. I liked the recent Clarion article, which, whilst aiming to be as fair and balanced as possible, still only skimmed the surface and didn’t fully give the picture as to why SESRO could be problematic. To be fair, it would have needed to be much longer to do that.

I’m trying to address that here. This is the first of three articles that go into a real deep dive (and you wouldn’t believe how difficult it’s been to avoid a pun on that). This first one will be an overview of the situation behind it all: the water status of the country, the National Infrastructure Commission’s review, and the various options for changing the equation of water demand versus water supply, as well as the actual options for water infrastructure (responding to the claimed “there is no alternative”).

The second will be on the specific problems and issues of the proposed SESRO mega-reservoir, and the third will be on the costs of it – not just financial, and exploring what they’ll actually be rather than what they’re claimed to be, and then back to covering what we could do.

Before I start, I’d like to mention that I started out on the “pro-SESRO” side. I like reservoirs, I like bodies of water, and I am fully convinced of the need to provide the infrastructure our growing population requires.

Unfortunately, when I went from a mild dusting of knowledge to digging deeper and deeper, I found myself inexorably swinging to the “anti” side – and for a lot of good reasons. GARD (Group Against Reservoir Development) lead the resistance to the reservoir (it’s sort of inherent in the name). I am not a member of GARD. I’ve insisted on retaining my independence, emphasising my right to change my mind as well.

I was made “Water Champion” of the Vale of White Horse District Council a year or so ago, mainly due to the fact that I’d been head down in hundreds upon hundreds of pages of detail, submissions, independent analyses, proposals, and arguments over the proposed SESRO project, which is by far the largest factor in any water elements in this area. This proposal is also inherently linked with the wider factors of droughts and flooding, so I automatically ended up learning a lot about these. There was a fascinating Water Supply Summit in Oxford in November 2022, with the Met Office, Thames Water, multiple experts, Oxfordshire County Council, GARD, Affinity Water, the National Farmers Union, and others, where we all explored the various challenges and options around future water supply. I’m writing this as a councillor, but not as an official stance of Vale of White Horse District Council itself.

Bottom Line Up Front

I’ll sum up at the end, but a “bottom line up front” goes something like this:

- This wasn’t what the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) called for in the first place, other than trying to sneak in under the “and other infrastructure as necessary” heading.

- It drives out the much cheaper, quicker, less disruptive, and more effective solution that was more explicitly called for, partly because the latter (the Severn-Thames Transfer, or STT, as part of the proposed National Water Grid) instantly makes the reservoir unnecessary.

- This is no normal reservoir. It’s a true megaproject of unparalleled scale for the type of construction involved. It comes with a lot of unknowns, many of which threaten such things as repeated floods, serious disruption, large-scale environmental damage, outright ongoing dangers, and more.

- It would also provide much less drought resilience than we’d like.

- There’s a very real chance that the much-touted recreational benefits would never materialise.

- It’s near certain to come in at a multiple of the promised price and take several times longer to build than suggested, whilst the alternatives would be much less likely to overrun.

- It kills off any opportunity to do anything else there.

And there are so many better alternatives.

- Focusing on the reduction of leaks, plugging in the updated population figures, and adjusting abstraction levels, which (with the other water infrastructure already to be built) could remove the need for SESRO in the first place.

- If we do decide we want more resilience than that, the NIC’s National Water Grid is the first port of call: the Severn-Thames Transfer would be faster, cheaper, more effective, more resilient, more adaptable, and far less disruptive.

- If we are resolved on reservoirs, then multiple smaller reservoirs (similar in size to the largest comparable reservoirs built in this country), dispersed and held forward instead, would face much less local resistance, have fewer issues, be cheaper and quicker, and, again, more resilient and adaptable.

- If we’re truly looking at climate-change-proofing our water infrastructure, we should look harder at the newer technology for desalination and/or water re-use.

Jaws of death?

There have been worries about the “jaws of death” for some time, water-wise. This ‘<’ shape is what happens if you plot a graph with water demand (the upward slope) against supply (the downward slope). The phrase was coined by a previous Environment Agency chair for the expected period when demand would rise thanks to population growth, while supply would decline thanks to climate change.

In 2018, the independent National Infrastructure Commission looked into it. Punching in the then projected population growth statistics, the climate change expectations, and imposing a further reduction in water abstraction, plus an increased resilience requirement beyond where we are at the moment, it’s fair to say they stress-tested the solution. If we followed their recommendations, we’d definitely be safe, with considerable safety margin – albeit at a big expenditure on capital projects (the money coming from water customers).

However, our population, whilst increasing, is now doing so slower and will peak at a lower level. There’s also a strong case for not reducing water abstraction as much as suggested.

When I started looking into this I thought we got all (or most) of our water from reservoirs. Not so. The default is abstraction – taking water from aquifers, rivers, and streams. Reservoirs only kick in occasionally. But we’ve been abstracting so much water from some sources, particularly delicate chalk streams, that those watercourses are in peril: they rely on water flow for their shape and ecology. Few would disagree with reducing (or removing) abstraction from chalk streams and other more delicate sources.

An abstract problem

Are we going about this the wrong way?

GARD has pointed out that the abstraction reduction policy has been extended far broader than the watercourses that actually need this help. For example, take the lower River Lea and Colne, which are already modified and ‘canalised’ so the water doesn’t naturally govern their courses or ecology. Abstraction reduction in these merely means more fresh water flows out towards the sea; it doesn’t do much for ecology. (We’re talking a difference in water resources in the hundreds of millions of litres per day; the abstraction reduction required from the lower Lea alone isn’t far off half of SESRO’s maximum unsustainable output.)

Add this back in; add in the proposed leakage reduction and consumption reduction that the NIC propose; use the latest population figures and other infrastructure additions that are further along and less disruptive; and the entire SESRO justification evaporates.

It’s not just GARD saying this. The Chalk Streams First campaign pointed out that reducing abstraction from the upper chalk streams (which is agreed to be essential) doesn’t mean we’d end up losing much abstraction in total: you can simply pick up 90% of the same water lower down the river. We could, if anything, accelerate the rescue of the chalk streams at very little cost in abstraction. We could even pipe the water from lower down back to the headwaters to help recovery, given that we still end up picking up 90% of whatever we pipe back up when abstracting lower down.

At a Thames Water SESRO outreach event, I was quietly told by a Thames Water delegate: “What I’d do in your shoes is challenge the abstraction reductions and the obsolete population projections. Get those resolved and SESRO just goes away.”

Solving the problem nationally

I’ve mentioned increasing leakage reduction. In the Water Supply Summit I mentioned earlier, when we broke out into groups to dig deeper for solutions, one delegate challenged us to go further than suggested on leakage reduction. That delegate was a Thames Water contractor.

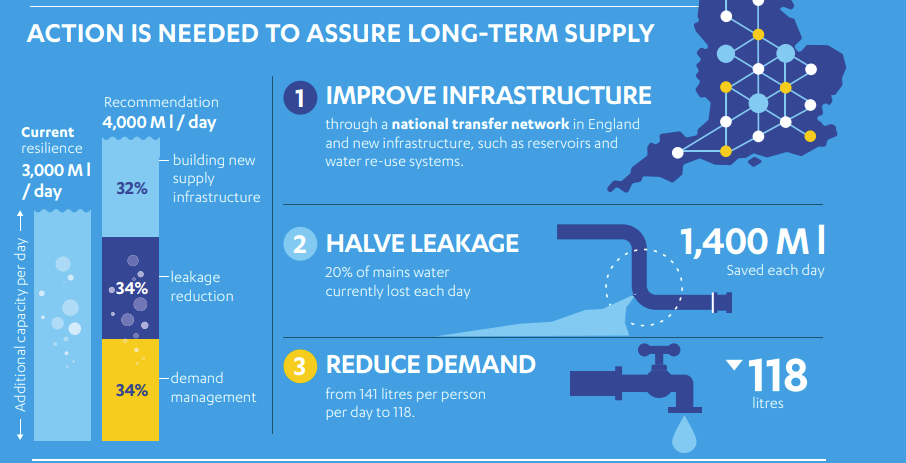

I personally prefer the belt-and-braces solution from the NIC (above). You’ll notice two things: firstly, that they’re increasing from “current resilience” of 3000 million litres per day to 4,000. Secondly, that the solution is three-fold: reducing leakage and reducing demand are each bigger elements than all new supply infrastructure put together.

What do they mean by “current resilience”? That’s how much more they calculate we need, with expected climate change and the (then) projected population increase projections, in order to preserve our current 1-in-200 years drought resilience. In other words, we’d only have real problems in the face of a drought so severe that we’d see it once every two hundred years, even bearing in mind climate change and population increases. That’s why we need an extra 3,000 million litres per day. They’re recommending further increasing to 4,000 million litres of resilience in order to be so resilient that we’d only have issues from a 1-in-500 year drought.

To do this, you can increase supplies or decrease consumption – or, more usefully, a combination of both.

The first way to decrease consumption is to decrease the amount that’s wasted. We currently leak out 20% of all our water between supply and the tap – 2,800 million litres per day simply wasted. Halving that saves 1,400 million litres per day. It gets us almost halfway to our current resilience at a stroke, and more than a third of the way towards our new and improved resilience target – all taking climate change and population growth into account. Every 2% reduction in leakage, from our current 20% of water leaked, is more than the maximum output from SESRO in ideal conditions, with no chance of ever running out.

The next way to decrease consumption is, simply, to decrease the amount we use. Our demand for water has increased from 85 litres per person per day in the 1960s to 141 litres per day today. Getting that down to 118 litres per person per day is very achievable. In fact, installing water meters so we can see how much we use (and pay for) tends to see water usage drop from 141 litres per person per day down to about 120, without any other measures being taken. (The latest Government guidelines suggest 110 litres per person per day; in Denmark, they’re down to only 98.)

Reducing demand by 4.5 litres per person equates to the maximum output of SESRO. These two measures would get us to a resilience of either 2,800 million litres per day (on the original recommended demand reduction to 118 litres) or around 3,200 million litres per day (on the newer guidelines of 110 litres).

But what about new infrastructure?

Still, the NIC recommended new infrastructure. Yes, it’s the smallest of the three action areas, but if we want to be more resilient than today, we’ll need to build.

But why is the lead element, in bold, saying “national transfer network” whilst and only mentioning reservoirs in passing?

The NIC, quite correctly, looked at all water infrastructure. This includes water re-use, desalination, water transfers, as well as reservoirs. This may surprise you, given that virtually all of the public discussion on water infrastructure is about reservoirs. It’s as if we all assume all our water comes from reservoirs, like I originally did.

Only when things get so dry that we can’t abstract enough water from rivers, streams, and underwater aquifers do we draw upon reservoirs (filled during the wetter times, ideally). But reservoirs do have drawbacks. Not only do they require large areas of land, they cause carbon emissions when drawing down (as decaying plant matter becomes exposed); they require considerable maintenance (you don’t want a dam breach!), and a lot of care (algal blooms and filling up with sediment are perennial problems). We’ll go into those in the next article.

Desalination – removing salt from seawater – is useful when you’re an island, but the NIC pointed out that it can be energy intensive and produce quantities of very salted brackish water. However, since 2018, there have been considerable improvements in technology that can reduce these negatives considerably. These could make this a better long-term option – and, given that we are an island, very climate-change-proof.

Re-use of waste water is a workable option, but the NIC noted that it has more limited availability, and tends to produce pushback from the public – even though abstracted water also requires work to clean. (Trust me, you don’t want to drink raw water.) Again, improved technology and infrastructure might make this a considerably better option in the longer-term.

But the most important is water transfers – getting water from where it is, in the wetter parts of the country, to where it’s needed, in the drier parts. I was genuinely surprised to learn that we don’t already have a national water transfer system. The NIC pointed out that this was the only one of the four to always end up with a positive cost-benefit. In their own words:

“A range of studies have all found a positive cost-benefit case for greater transfers and water trading. However, transfers currently only make up a small proportion of total supply (about 4%). This is likely to be because the incentives in the current system make developing a strategic transfer network difficult.

“Transfers can move water from areas with surplus to those where it is needed. In addition, they enhance resilience because […] new storage or other supply could be provided in a wider range of places, which can reduce costs and increase the likelihood of timely delivery.

“A network of strategic transfers could potentially provide about 700 Ml/day more capacity, at costs comparable with other options and increased adaptability of the overall system. The remaining capacity should be provided by the most cost-effective combination of supply infrastructure.”

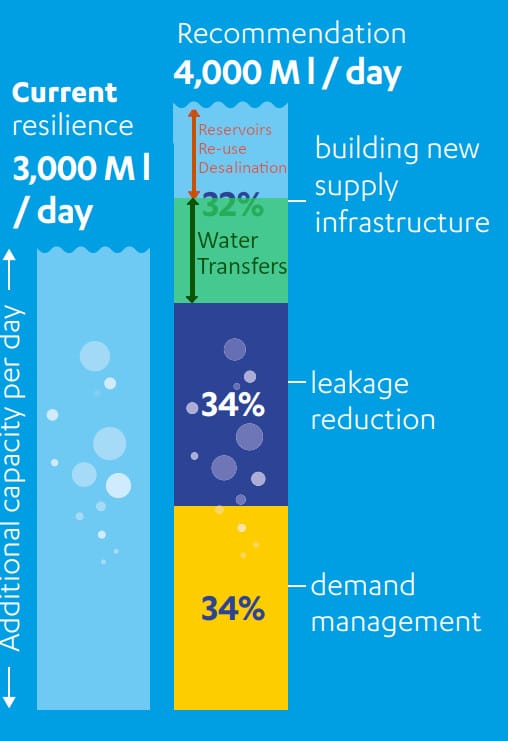

Here, I’ve overlayed the proposed breakdown of water transfers and “the rest” on top of that NIC diagram from earlier. Reduced demand, reduced leakage, and then the water transfer network gets us well beyond our current resilience and leaves only about 600 million litres per day (of that 4,000).

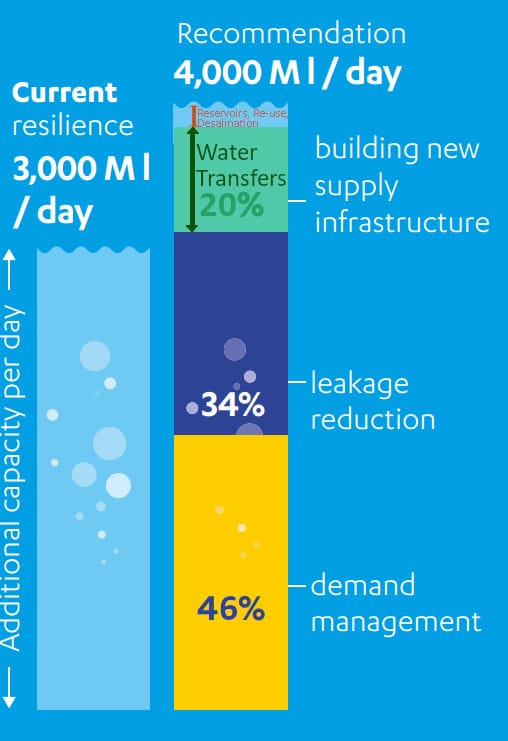

If we put in the new consumption reduction requirements to 110 litres per person per day, and retain the same leakage reduction and recommended water transfers, and overlay that on the NIC diagram, it looks even more stark:

Using the NIC’s figures, that extra 8 litres (from 23 saved to 31) adds up to another 12% of the requirement. Keeping the leakage reduction and water transfers the same (which, given that neither has any significant negatives) means that the rest of the infrastructure needed gets squeezed way down, to as little as 100 million litres per day. This, remember, includes re-use and desalination. Again, SESRO vanishes.

Of course, this would assume we build all that 700 million litre/day transfer network; that we increase resilience to the full 4,000 million litres per day; and that the population grows as fast as the 2014 projections suggested. We may well decide to build other supply infrastructure. But it’s certainly the case that there are plenty of choices we could make.

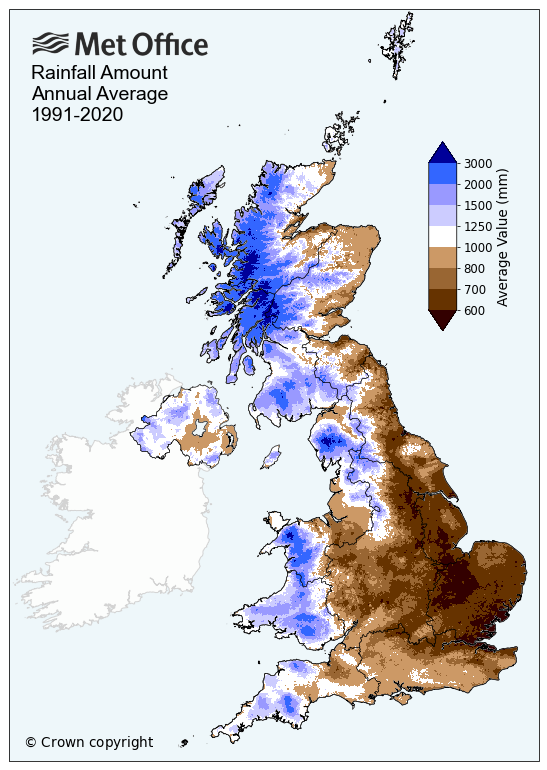

Get it where it’s wet

We don’t have a water shortage problem on this island. We have a water distribution problem. In the north-west, up to six times as much rain falls as in the water-stressed south-east. The rain in Spain may fall mainly on the plain; here, it falls in the west and north, in the hills and mountains.

If you live in the north-west of England, or in Wales, or western Scotland, you’ll have noticed this. We live on a wet and rainy island. We just need to get water from where it falls to where we want it.

Again, the NIC says:

“A network of strategic transfers could potentially provide about 700 Ml/day more capacity, at costs comparable with other options and increased adaptability of the overall system. The remaining capacity should be provided by the most cost-effective combination of supply infrastructure.”

That last sentence is where supporters of SESRO declare that it comes in. And yes, it does say that we could have reservoirs, if they prove to be the best option in and among desalination and re-use. But the first thing up-front should be the strategic transfer system. I think that’s pretty clear.

It seems daft that we don’t have a National Water Grid yet, and it would give huge resilience to unexpected shocks. Importantly, the Severn-Thames Transfer – a key link in such a transfer system – is much easier to adapt up or down as we approve, design, build, and even operate. This is why it’s my preferred solution, and that of others. Indeed, within regions, we’re seeing companies building internal transfer systems already.

RAPID… but slow

The water companies are naturally focused on themselves. National water transfer systems don’t fall under any of them. Accordingly, a programme called RAPID (Regulators’ Alliance for Progressing Infrastructure Development) was set up in 2019 with the intent of coming up with a nationwide strategic plan for water infrastructure. They’ve been progressing through steps in that process (called “Gates”) ever since.

Throughout it all, the water transfer ideas have been resisted by water companies – at least, those who would receive the water. Those who’d be exporting and selling it are actually pretty happy with the idea! It’s understandable: the recipients would have to pay the exporters, and be dependent on them at times. Commercially, it makes sense to have all your water under your own control, or to be able to export it. (Ironically, whilst Thames Water are vehemently resisting importing water via STT, they’re all over the idea of exporting water out of the most water-stressed area in the country – the Thames Valley.)

This is why RAPID was set up in the first place. Water companies aren’t set up to make the best decisions when water transfer options are taken into account. That’s why higher-level decisions need to be made: water companies’ commercial preferences can’t outweigh what is best for the entire country. Government could even set up a Water Transfer Authority to take away the commercial risk if necessary.

Rather than the transfer system, Thames Water would prefer SESRO in a place of their own control, regardless of cost, disruption, damage, or delays, or even whether it would have the resilience needed. Left to their own choices, they would sideline the proposed Severn–Thames Transfer, the key link between the wet west and the dry east. RAPID haven’t finished their work, but the new Government have skipped past it and approved Thames Water’s latest Water Resource Management Plan (despite the Environment Agency saying it’s not fit for purpose), which claims the need for SESRO, but not a Severn–Thames Transfer.

We’re hoping that the Government takes a moment to reflect and goes back to the nationwide strategic approach.

We haven’t built new reservoirs since… when? And why?

Most of this gets skipped past in public announcements, press releases, and media commentary. It invariably goes straight to “Reservoirs! Now!”, and then straight to “we haven’t built a new reservoir since the 1990s”.

This isn’t completely true. New reservoirs have been built in the South West (like Hawks’ Tor), but, to be fair, they’re in the 1-2 billion litre size; an average reservoir is closer to 3-4 billion litres. We’ve also massively enlarged Abberton Reservoir as recently as 2013, from 25 billion to 41 billion litres. This isn’t technically building a new reservoir, but if it’s equivalent to building four or five medium-sized reservoirs in its effect.

Whilst getting approval for more reservoir capacity is a challenge, it’s obviously not impossible (as new small reservoirs and expanded existing reservoirs show). And water companies are obviously more than happy to build (or enlarge) reservoirs. So why no totally brand new and large reservoirs since the Nineties?

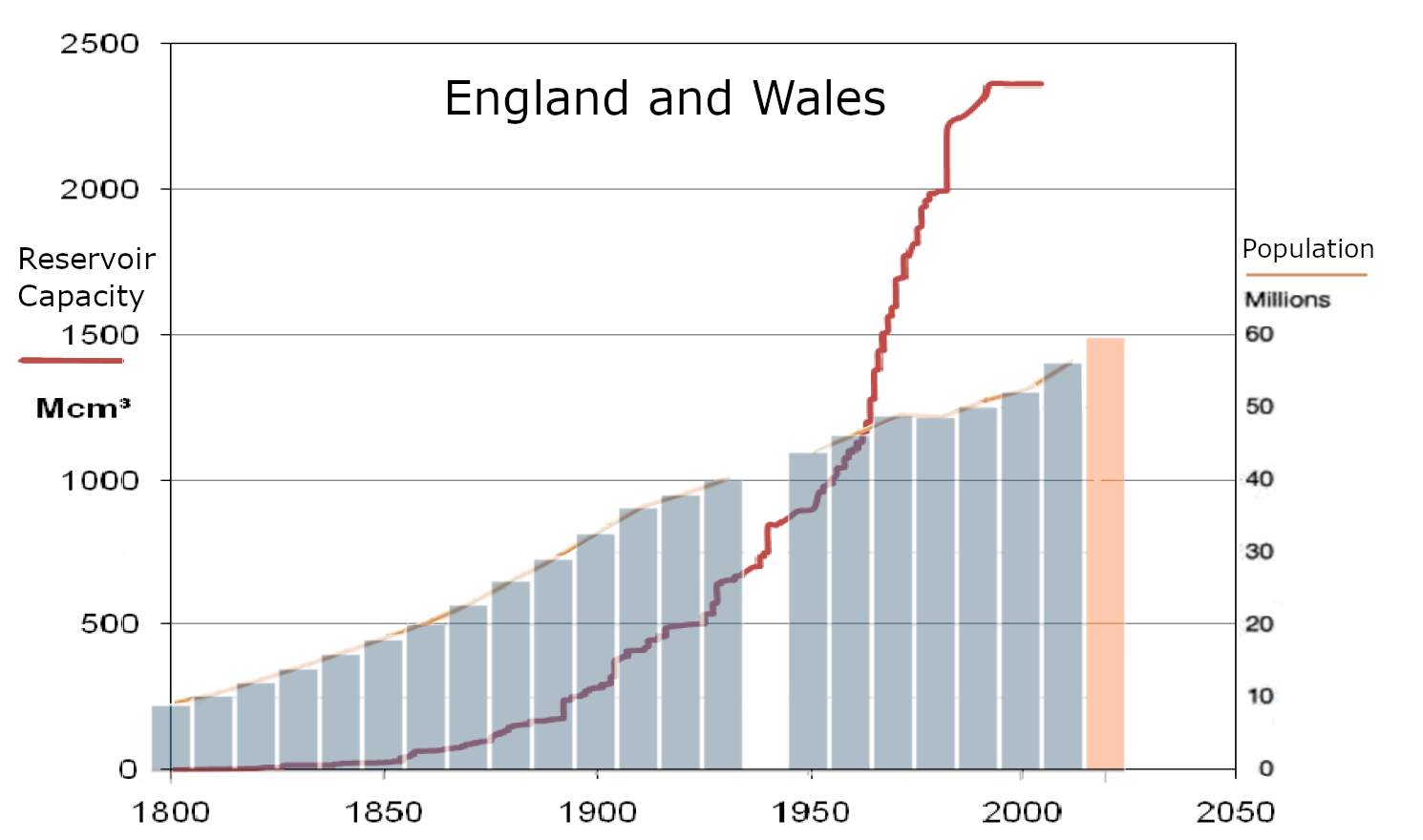

One answer is here:

That’s population against reservoir capacity over time. We built a lot of reservoir capacity in a pretty short space of time. Rather than a sign we’ve fallen behind, it’s because we’d run ahead in that short while. Big reservoirs are expensive and disruptive – it’s a challenge to justify them, especially when you’ve just doubled your reservoir capacity in a couple of decades.

As it happens, the last public inquiry into an Abingdon reservoir site (in the 2000s) gave a thumbs-up to a reservoir. While it found that the 100 billion litre option couldn’t be justified, it decided that a 50 billion litre one was justifiable. That response would mean a full submission to the Secretary of State would be pretty much locked-on to get approval. But instead, Thames Water took their bat and ball and went home, rather than build the 50 billion litre option.

Where next?

In this article I’ve set out our realistic options – as well as how we’ve ended up where we are, with all the noise focusing not only just on reservoirs, but mainly on a specific super-colossal built-up bunded reservoir in Oxfordshire.

The next article will look at how big is “big” (are we overstating this?) and what the problems actually are with such a huge reservoir. Then, in the third one we’ll look at the challenges of actually building it – and at what cost. It’ll finish with the wider options repeated and expanded.

If you’d like to dig yet deeper, find out more about the reports and analyses to which I refer, or ask for more detail, just contact me on my council email address, Andy.Cooke@whitehorsedc.gov.uk.