Housing Week: Building Out – can Oxfordshire solve Oxford's housing crisis?

This week we’ve examined the challenges in building within the Oxford Ring Road, building upwards, and building in the Green Belt. Where can you build? One answer remains: rural Oxfordshire.

The scale of building planned for Oxfordshire is breathtaking. The big towns, like Banbury, Didcot and Witney, are getting bigger. So too are minnows like Watlington and Eynsham. A few edge-of-Oxford locations are being winnowed out of the Green Belt, at Sandhills and Water Eaton. Then there are the all-new towns: Heyford Park, Culham, Salt Cross, Begbroke Science Village.

Oxfordshire’s protected areas will be mostly unaffected. The county’s three upland areas – Cotswolds, Chilterns, North Wessex Downs – are all National Landscapes, aka Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Development here is not impossible, but prone to legal challenge, and so the district councils have largely left them alone. Settlements like Burford, Charlbury, and Goring-on-Thames won’t expand much if at all. (An urban extension is lined up for Chipping Norton, but just a few metres outside the Cotswold boundary.)

The county’s four rural district councils (Cherwell, West Oxon, South Oxon, Vale of White Horse) are the planning authorities. It’s their job to decide where the houses go. They do this in documents called Local Plans, which are the planning rules for a district. A Local Plan typically mixes the maddeningly specific (“Witney sub-area: 4,702 homes”) with the inane (“All development should be of a proportionate and appropriate scale to its context having regard to the potential cumulative impact of development in the locality” – thanks for that, we’d thought you were going to propose disproportionate and inappropriate houses).

But they matter – enormously. Your Clarion scribes have sat through afternoons at Local Plan examinations. A belettered planning inspector peers over his glasses at district council planning officers, while a phalanx of smooth lobbyists and lawyers representing David Barratt Bovis Persimmon Plc try to eke out every opportunity for profit and smooth off every requirement to spend money. An occasional bearded parish councillor will turn up to meekly ask that their village is spared, and the inspector will look upon them with an avuncular eye, before concluding their request has no basis in planning law and moving swiftly on.

We confess to finding this process skull-crushingly boring and staggeringly complicated in equal measure. We say that as people who choose to spend their afternoons live-tweeting council meetings. For developers, though, the very success of their business is at stake. That farmer who you’ve been subtly courting over the last few years? If the Local Plan identifies his land as suitable development, he, and you, are quids in. That old quarry in the AONB? Inspector, respectfully, in the light of national planning guidance, we think an exception could be carved out for that.

Eventually, the Local Plan emerges into the cold light of day. The district council breathes a brief sigh of relief. The parish council is left wondering whether it can do anything to stop 1,500 homes being built on what was Manor Farm. Meanwhile, Farmer Giles starts leafing through yacht catalogues.

Employment

Half of Oxford’s workforce lives outside the city, and the proportion is growing. The city is doubling down on its reputation as a hothouse for knowledge workers, with former retail buildings and light industry being turned over to the ubiquitous “lab space”. Osney Mead, Oxpens, Oxford North, ARC Oxford, Oxford Science Park – all are expanding to attract still more inbound commuters.

But Oxford’s role as employment centre is not limited to lab-coated scientists. Take the NHS, among the county’s top five employers. Over the past 20 years, Oxfordshire’s health provision has become centralised around the Headington hospitals, with Banbury’s Horton Hospital being controversially downgraded. (Should you want an illustration of the transport issues that come from concentrating everything in Oxford, ask those Oxfordshire villagers who have seen “blues and twos” increasingly replaced by air ambulances. Helicopters don’t get stuck on the A40.)

Outside Oxford, the county’s great economic success is Science Vale. Inspired by university spinouts and the tradition of research at Harwell and Culham, it is Oxford’s answer to Cambridge’s Silicon Fen. A cluster of hi-tech research businesses with international reputations, located at the Harwell Campus, Milton Park, and other sites around Didcot, Abingdon and Wantage, it is now a significant commuting destination in itself – even for residents of Oxford itself.

There are early signs that Motorsport Valley could become Oxfordshire’s next growth hotspot, with a clutch of electric vehicle startups around Bicester and Banbury. The visitor economy, already so crucial to Oxford, is broadening too. The West Oxfordshire Cotswolds are becoming a weekending hotspot for Londoners at play, while the mooted Puy de Fou theme park near Bicester could create hundreds of jobs.

Yet as traditional industries falter, the county needs to run to stand still. Douwe Egberts in Banbury, once a major employer, is now just a packaging plant. RAF Brize Norton’s expansion masks the gradual running down of the county’s other military bases. Online shopping and working from home are worrying trends for market towns that once thrived from High Street retail.

Oxford’s economy is secure. Oxfordshire’s is better placed than many rural counties, but in no position to rest on its laurels.

Transport

Why does this matter? What harm is done if Oxford workers live in Wantage, Carterton or Bicester? There are issues of community cohesion and demographic mixing – the desire to not just become a dormitory town. We’ll touch on that later! But the Day One problem is transport. 100,000 new homes are being built in Oxfordshire in the next 10 years. This could add up to 140,000 cars. Many, perhaps most of them will commute towards Oxford.

As we reported last week, the investment in speeding county commuters to Oxford jobs is immense. £332m on the Didcot/Clifton Hampden relief road. £180m on the A40. A series of smaller projects around the county, each tipping into eight figures. One way of looking at this is the investment needed to enable new homes. Another way is that it’s spending £0.5bn so that commuters can live further from their workplace.

Whichever way you take it, it’s an inevitable consequence of building further out in Oxfordshire. But it won’t stop there. The lesson of Oxfordshire roads this millennium is that there’s always a pinch point to ease, a roundabout to rework, a last inch of capacity to squeeze out. The road building never stops.

Is there another way?

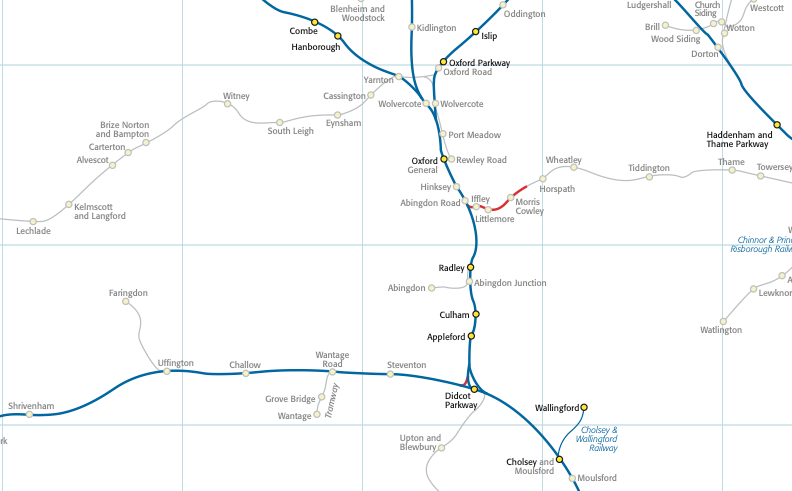

Oxfordshire is enjoying a rail renaissance. Oxford used to be an “outer suburban” terminus for cramped three-coach rattlers from Paddington. Now it has a 125mph intercity train every half hour. Oxford Parkway is the all-new station that made Cutteslowe a property hotspot overnight. And next year, East-West Rail will link the city direct to Milton Keynes and beyond.

The county’s ambitions are high. Wantage and Grove have a population of 20,000 plus, and growing. The railway runs right past them: a station seems a no-brainer. Cowley still has a branch railway, used for shipping Minis out of Plant Oxford, which passes right by Oxford’s business parks: it is earmarked for reopening to passengers. Developers at Heyford Park and Begbroke have made non-committal noises about building new stations. More daring, but compelling, is the dream of rebuilding the old line to Eynsham and Witney.

Yet as anyone who has visited Botley Road recently will testify, the rail industry moves more slowly than a train inching up the slow tracks from Reading. The sums involved are vast: reopening to Witney would cost up to £900m. The electric overhead cables projected for Oxford still stop at Didcot after Network Rail ran spectacularly over budget.

After the Botley Road debacle, it would be a brave planner who bet the county’s future on the railways. In many cases, councils are betting on buses instead. A new bus lane has just been built in from Yarnton to Peartree, and another forms the crux of the £180m A40 scheme.

Cars, trains, buses… we would not be the Clarion if we skipped over bikes. 28% of trips in the Netherlands are by bike, aided by a dense network of safe, car-free tracks. Could rural Oxfordshire aspire to that? There are tentative signs it could. Networks are slowly taking root, particularly in Science Vale and the Kidlington–Eynsham corridor, though rarely to Dutch standards. The projected new roads all have cycle tracks as part of the design. But for a shift to bikes, people need to live near where they work. Few would cycle 11 miles from Didcot to Oxford – though e-bikes are stretching the range of what people will do.

(One of those “of course it’s like that” asides: the district councils are the planning authorities. The county council is the highways authority. Yes, that does mean that house-building and transport planning are done by entirely different people in entirely different offices, communicating via policy papers and financial bargaining, with the developers as occasional intermediaries. We don’t think we’re editorialising too strongly when we say, objectively, this is a silly way to plan a country.)

Design

Where do you want to live?

Living in Oxford is, in so many ways, fabulous. We don’t really want to start an East Oxford vs Jericho vs Osney Island vs Summertown argument in our comments (ok, ok, maybe we do). But it’s not hard to see why, employment aside, Oxford is a draw for so many people. From the shops to the pubs to the schools to the parks, it’s not half bad, is it?

And you could say the same of much of Oxfordshire. We don’t really want to start a Wallingford vs Chipping Norton vs Watlington vs Charlbury argument in our comments (ok, ok, maybe we do). Still, the Sunday Times Best Places to Live list always features a handful of Oxfordshire towns and villages, for good reason.

Will all these newbuilds be so desirable? Put down £500,000 for a brand new house in Didcot vs something less shiny in Chipping Norton. You’ll get a bigger garden. Maybe an extra en suite. For many people, that’s a clincher. For others, history, greenspace and community outweigh the Rightmove tickboxes.

Which side are you? It’s your call. But we don’t think it’s a stretch to say that many people moving outside Oxford want a bit of the magic the city has. The old stereotype of “20-somethings in the city, 30-somethings in the suburbs” no longer holds true. Oxfordshire’s new towns need to be more than just houses. They need to be as good as living in Oxford. That means striving for the community feel of the sought-after market towns – perhaps more.

It requires thoughtful design. It means creating the “third places” where community happens, even if there’s no immediate ROI for the developer:

The term, which was coined by the sociologist Ray Oldenburg in the 1980s, essentially refers to a physical location other than work or home where there’s little to no financial barrier to entry and where conversation is the primary activity. The historical examples that Oldenburg cites in his book The Great Good Place include French cafés, German American beer gardens, and English pubs, all of which appeal to people from various walks of life.

Watlington has 2,700 residents, three pubs and three churches. Charlbury has 3,000 residents, four pubs and five churches. The new town of Heyford Park already has 2,500 residents, but no pub and just one little chapel. Even Carterton, most of which is post-war, has only a couple of pubs for its population of 18,000. Community doesn’t just happen.

Infrastructure

A village isn’t a village on vibes alone. Residents need infrastructure. They need schools, GPs’ surgeries, grocery stores, and the even less glamorous stuff like water and sewage. To build a giant town requires giant infrastructure.

Building that infrastructure doesn’t come easy. Are Thames Water’s mooted Abingdon Reservoir, or the even more controversial Botley West Solar Farm, essential infrastructure for a growing population – or still more urbanisation of the countryside? Well organised campaign groups like GARD and Stop Botley West are making the case against.

Meanwhile, Oxfordshire’s inadequate sewage treatment works are currently blocking further development in Oxford itself. With sewage regularly overflowing into rural rivers like the Cherwell, Windrush and Evenlode, we expect STW capacity to become a crunch issue for county developments, too.

Building the infrastructure is only half the battle. Paying for it is the other half. Traditionally, developers are given an itemised bill for the infrastructure required by their new houses. This is known as Section 106 funding, after the clause in 1990’s planning act. It’s now been joined by Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) – a similar concept, but one which is designed to recognise that the infrastructure burden extends beyond the immediate site and into the wider district.

Remember the phalanx of smooth lobbyists and lawyers we last saw at the Local Plan examination? They come back onto the stage here. It is, they plead, a hard life being a developer. If you are toooo demanding with the S106 and CIL obligations, our developments will be uneconomic and we will be unable to feed our little lobbyist children. (At this point a steely glint enters their eyes.) And if the houses aren’t economic for us to build, then that Local Plan, in which you promised the Government you’d build 30,000 homes, falls apart. At which point we can build what we like, where we like. So: sign here to let us off?

Take a look at West Oxfordshire. The district’s Local Plan concentrates development in a small number of “strategic sites”: Eynsham, Witney, Carterton, each lined up for thousands of homes. Putting all the eggs in a few baskets like this increases the jeopardy from construction, or other, delays (the Clarion has been told that some estates are selling rather slower than expected). Earlier this year, West Oxfordshire was deemed to be falling behind on new homes – technically, it couldn’t demonstrate a “five-year housing land supply”. When that happens, developers are allowed to propose sites outside the Local Plan. Phones start ringing. “Hello, Farmer Giles? Ah, you’re in Cannes on your satellite phone. Jolly good. Tell me, do any of your mates down the NFU have any spare fields going?”

As a result, district councils are nervous about rinsing the developers for infrastructure, lest they pull out of schemes entirely. The southern Oxfordshire councils and Oxford City all have CIL up and running, but Cherwell and West Oxfordshire don’t – they are trying to introduce it right now. In both cases, the massive newbuild schemes (Heyford Park, Salt Cross) will be entirely exempt from CIL: that is, the biggest developments will pay the least towards infrastructure. (Another example: BMW was let off the £830,000 of CIL it would have normally paid, as Oxford City Council was anxious to keep Mini jobs in Oxford.)

There is a curious coda to all of this. Oxfordshire’s councils have done pretty well in collecting Section 106 and CIL money. They have done less well at spending it. Oxfordshire County Council has £278m of developer-paid infrastructure funds just sitting in the bank, unspent. We delved into this in May.

Where next?

Make no mistake, all of this swings elections. The LibDem wave in rural Oxfordshire was partly inspired by alarm at the housing targets set by Conservative-controlled district councils. After the Conservatives lost control of South Oxfordshire to the LibDems and Greens, the then Secretary of State, Robert Jenrick, ordered South Oxfordshire District Council to rubberstamp these plans, whatever qualms they might have. (Robert Jenrick is currently the frontrunner to become the next Conservative leader.)

The LibDems themselves have a perennial tension between local opposition to new developments – often characterised as NIMBYism – and a national policy that promotes building new houses. Labour, meanwhile, is now faced with working out how to fulfil its promise of 1.5m new homes. Their new Banbury MP Sean Woodcock proudly proclaimed “I’m a YIMBY!” [Yes, In My Back Yard]. His electors in Banbury town won’t desert him over that – they will probably rather like it. But will rural voters in Heyford start wavering?

Have a little sympathy for the candidates seeking your support in May’s local elections. All of this is a jigsaw, or perhaps, a fiendishly complicated simultaneous equation. In this week’s articles we’ve juggled (deep breath) transport, social equity, views, heritage, employment, greenspace, design, sewage, community, tourism, and profit. It’s hard to balance all those. It’s even harder to do that and still get elected.

Postscript

In truth, the reason your Clarion scribes started writing this series is that, in the two years we’ve been running, the more we wrote, the more we realised everything comes down to housing. Stuck in a traffic jam? More houses built without the right infrastructure. Annoyed about a reservoir? The people of Oxfordshire need to drink and shower. A solar farm? We need to charge our phones and power our kettles in the 100,000 new homes with something. Cost of living crisis? Have a look at your rent/mortgage payments and consider the laws of supply and demand.

We could go on. But mysteriously, no one talks about this, about where houses go or how they’re built. It’s barely in election leaflets, it certainly doesn't make the press. (Perhaps a cute press release about heat pumps or solar panels.)

We don’t have any easy answers. But we hope our week-long dive into Oxford’s housing crisis has got you thinking or talking. Get involved. If a campaigner knocks on your door, ask them what their party’s policy is on delivering the homes Oxfordshire needs, and the infrastructure that supports them. Write to your local councillor. Even better, stand as a local councillor. Whatever your political flavour, people like you make the difference.

Did you enjoy this series? We are the Oxford Clarion, an independent news outlet for Oxfordshire. This week was Housing Week, but each day on Twitter we provide a curated news feed on local issues that affect us all. From planning, to travel, to the universities, healthcare, and everything in between. Town and gown, councils and parliament, city and county. With the occasional puppy. On Friday lunchtime we round that up and deliver it to your inbox, for free. If you like the sound of this, hit the subscribe button and tell your friends.