Housing Week: Building Up, or view cones vs the dreaming spires

Opening the Clarion’s Housing Week yesterday, we noted that Oxford is the second most expensive place to live in Britain, after Kensington & Chelsea.

London, famously, has built upwards. The Shard. The Gherkin. The Walkie-Talkie. The Cheesegrater. The Scalpel. We promise we have not made any of these up.

Oxford hasn’t. Why not? In the second part of our series, we elevate (did you see what we did there?) one of the key barriers to building in Oxford City. But for a tl;dr summary: Can’t build here, mate. Bloke called Turner painted it once. Who d’you think you are, Ken Livingstone?

Did you know Oxford’s skyline was protected?

Indeed, did you know that skylines could be protected at all? Nor did we, until someone sent us a tip asking us to investigate “view cones”. (We like emails like that.)

Yes, planning laws govern whether you can build an extension, and how tall it is vs your neighbours house – but also how tall anything is, lest Oxford’s historic skyline be disrupted any further. Oxford's housing crisis, it seems, can't be solved by building our own Shard or Cheesegrater. But is this the last word?

This famous skyline, featured on many a picture postcard, has been painted by many artists – rather too many of them called Turner, including JMW Turner (painter of the Fighting Temeraire) and William Turner of Oxford.

Image 1 Oxford from Headingdon, JMW Turner, 1840. Image 2 View of Oxford from the River. William Turner of Oxford. c. 1789 - 1862.Image 3 Oxford from North Hinksey JMW Turner Image 4 Oxford from the South side of Headington JMW Turner 1803. Image 5 Oxford from Hinksey Hill, William Turner of Oxford.

It’s also been written about. The phrase “city of dreaming spires” was coined by Victorian poet Matthew Arnold:

This winter-eve is warm,

Humid the air! leafless, yet soft as spring,

The tender purple spray on copse and briers!

And that sweet city with her dreaming spires,

She needs not June for beauty's heightening,

It inspired Wordsworth in 1820:

Ye sacred nurseries of blooming youth!

In whose collegiate shelter England’s flowers

Expand, enjoying through their vernal hours

The air of liberty, the light of truth;

Much have ye suffered from Time’s gnawing tooth,

Yet, O ye spires of Oxford! domes and towers!

Gardens and groves! your presence overpowers

The soberness of reason; till, in sooth,

Transformed, and rushing on a bold exchange,

I slight my own belovèd Cam, to range

Where silver Isis leads my stripling feet;

Pace the long avenue, or glide adown

The stream-like windings of that glorious street,—

An eager novice robed in fluttering gown!

In both cases, note the juxtaposition of green space vs the dreaming spires. You'll see the same in the paintings. The skyline of Oxford is about more than simply the university buildings. This was described by ‘A Gentleman of Oxford’ in the New Guide to Oxford (first published in 1759):

The Town is situated on a broad eminence which arises so gradually as to be hardly perceptible, in the midst of a most beautiful extent of meadows, to the south, east and west and of corn fields to the north... From some of the surrounding hills, the traveller is surprised with an unparalleled prospect of magnificence and plenty; of numerous spires; domes, and turrets with the combined charms of verdure, water and trees.

It is this combination that is protected, not simply the buildings – though several buildings are singled out, such as the spires of the University Church and Lincoln College Library, the Radcliffe Camera and St George’s Tower.

Oxford isn’t alone in protecting its skyline. In London, famously, you may not block the view of St Paul's Cathedral. York and Edinburgh operate similar principles to Oxford. In brief, the logic is that there are locations where the quality of place is so distinctive, and the heritage sites so significant, that tall buildings will harm the setting – no matter how good the proposal’s design and architecture.

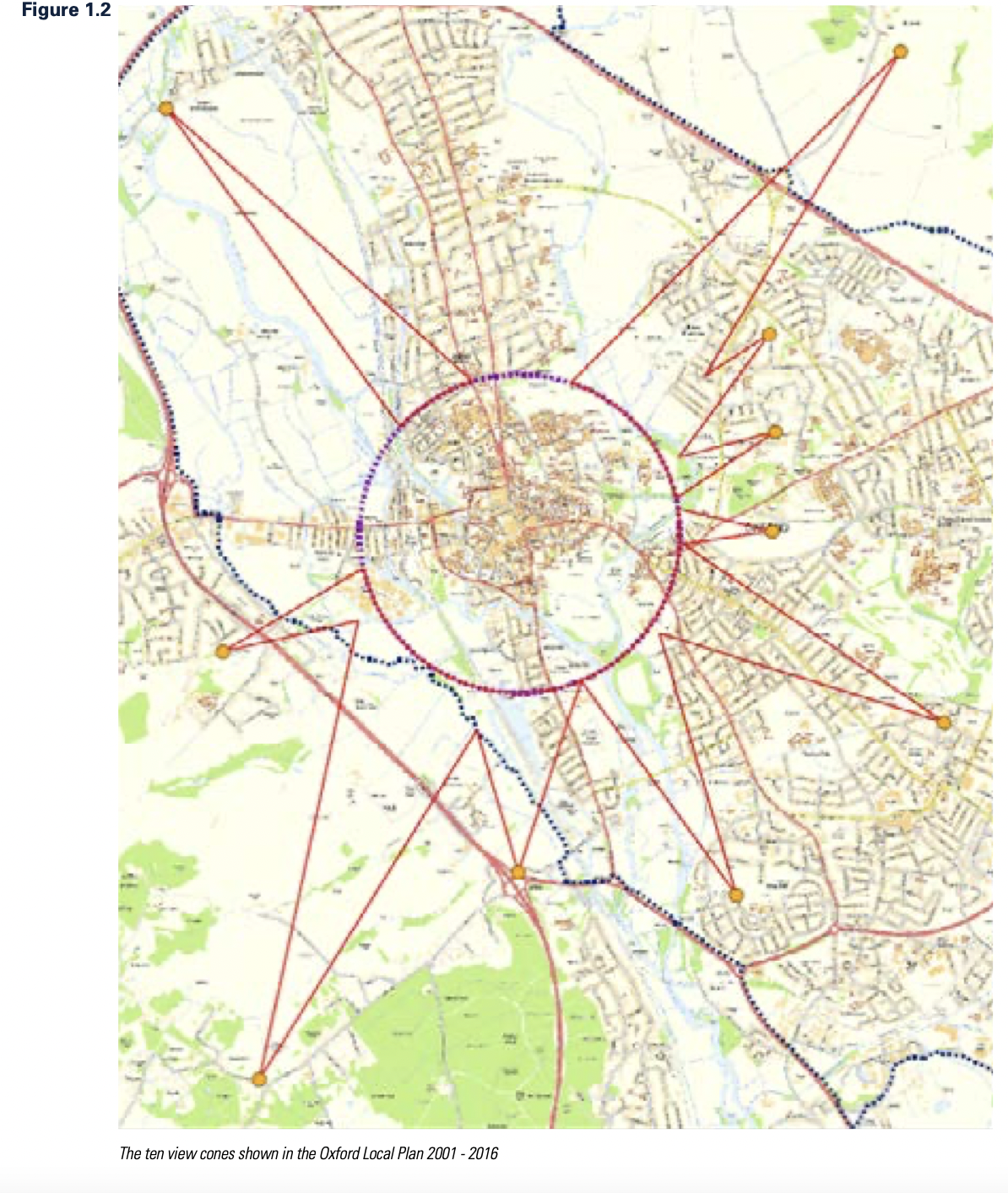

In Oxford’s case, according to the defining 2015 document on it (we read all 144 pages so you don't have to), plans must consider the views themselves; the viewers (who they were historically, how this would change, and the amenity they give to current viewers); and the depth of the view across the skyline. In particular, these are the identified views against which any application will be tested:

- Views from the Western Hills: Raleigh Park, Boars Hill and Hinksey Hill/ A34 interchange

- Views from the Thames Floodplain: Port Meadow

- Views from the North Eastern Hills: Elsfield

- Views from the Eastern Hills: Doris Field Memorial Park, Headington Hill Allotments, South Park.

- Views from South East Oxford: Crescent Road and Rose Hill

Put them on a map, and you can see why these are called “view cones”:

Let’s look at just one as an illustration.

Views from the Western Hills

Oxford from North Hinksey, JMW Turner. Oxford from North Hinksey today (from https://southhinksey.org/parish/nature-2/).

The view from Raleigh Park is freely accessible by anyone, residents and visitors. Matthew Arnold wrote about it, JMW Turner painted it. Various conservationists have it down as the view of Oxford.

The park itself was given to the people of the city by philanthopist Raymond Ffennell, for their enjoyment and to preserve the view of Oxford in its green setting. According to the City Council’s study of view cones:

The foreground of the parkland provides an attractive setting to the city that provides a strong contrast with the built up area, but does not contain structures that would distract from the view of the colleges and other historic buildings of the City Centre.

Here, the study makes aesthetic judgements. It sets out the attractiveness of the park, and the trees in North Hinksey and in the valley which help to set the city centre within a green landscape. It calls out Oxford Castle, on the western edge of the city, and more:

The historic high buildings stand above the general roofscape and form the focus of the view. The two groupings of high buildings seen from the east are also discernable in this view (the University Group focused on the Radcliffe Camera and the Christ Church Group focused on Tom Tower). These reflect the two foci of investment in prestigious architecture by patrons including Kings of England, bishops and magnates, among others. Both provide attractive groupings of historic buildings with a juxtaposition of attractive architectural detailing.

But Oxford has not always been successful in preserving this view. The assessment singles out the Oxford Mail’s former headquarters (1972) as “intrusive”:

The industrial buildings of Osney Mead have replaced the former open rural character of the meadows that formed the middle ground of the view up to the edge of the City Centre. They [...] draw the eye to the foreground and away from the historic high buildings of the City Centre. They have reduced the extent of the rural setting to the city that was historically part of both its aesthetic and evidential value and historic and artistic interest. The print hall of the Newsquest building is particularly intrusive, rising well above the general roofscape of Osney Mead with conspicuous blue cladding. From the main viewing point in the park it is in line with the buildings of Christ Church and competes with them for attention, marring the low level character of the middle ground of the view.

From a similar period are the John Radcliffe Hospital buildings:

Constructed in the 1960s and more recently, [they] have not generally been considered as having any aesthetic value. Early staff members referred to it in derogatory terms as ‘The John’ due to its appearance. The buildings break up the wooded slopes of Headington Hill that form the backdrop to the City Centre with a large mass of white rectilinear surfaces that draw the eye away from the historic high buildings marring the architectural character of the view.

The study makes recommendations for this particular view, including managing tree growth in the park; reducing the prominence of the print hall’s roof (which might happen as part of the Osney Mead redevelopment); and screening and restricting city centre development that detracts from the view.

As you can see from this précis, the analysis is detailed and considered. This level of detailed guidance is given to each one of the 10 view cones. It restricts not only building at height which would impact the existing skyline, but also the type of building materials used on lower rise buildings, and the green nature of the outskirts of Oxford.

This makes for a very sticky problem for developers, who already have high land costs in Oxford to contend with.

Stop the clock

This study, and the guidance that follows it, are in many ways an attempt to pause time – to keep the view as it always has been.

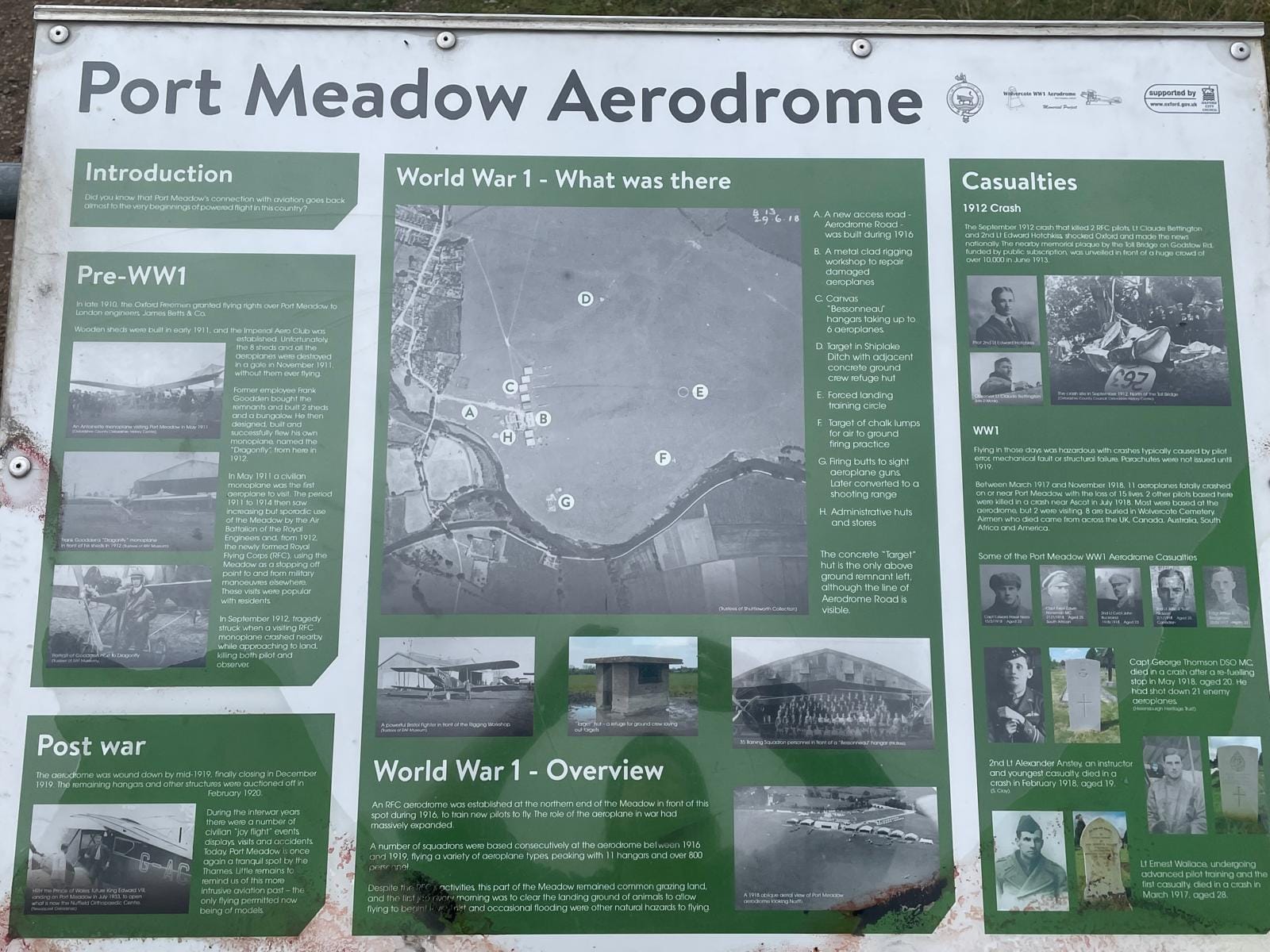

Racing at Port Meadow (Turner) and what's left of Port Meadow Aerodrome (Oxford Clarion)

Port Meadow is cited as a “history of uninterrupted use as common land, recorded in paintings throughout the last 300 years by artists, including Malchair, William Turner, James Aumonier, Sir Muirhead Bone and Peter de Wint.” But it has not remained unchanged through time. It has had Bronze Age barrows, Iron Age farmsteads, post-medieval quarrying, a 17th century horseracing course, and a First World War airfield. We are attempting to stop the clock now, before the marches of time and development march further and faster.

But perhaps a truer reflection of history would be reinstatement of the airfield. Who decides when the clock is stopped? Who decides what’s aesthetic? Is the Oxford Mail’s old HQ “intrusive”, or a startling example of European-influenced modernism? Where is it written down that Antony Gormley’s Iron Man, looking down on Broad Street, is acceptable – but a Hollywood style neon sign on top of the Rad Cam would not be?

AI image generated by Microsoft Copilot. To the best of our knowledge, no one.has proposed it. Antony Gormley’s Iron Man. (Philip Halling at geograph.org.uk, CC-BY-SA 2.0.)

Was it Kenough?

Returning to our comparison with London, the capital city provides a precedent for amending view cones. Former London mayor Ken Livingstone decreased the size of the “viewing cones” from 440m to 210m, amid pressure for avant garde tall buildings. 30 were constructed during his second mayoralty, including the Gherkin and the Shard.

Ken Livingstone. (Antony Robbins at Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0.) The ‘Big Four’ towers in London. (Michael Garnett at Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0.)

This was a deliberate policy change – and it’s hard to conceive of doing it any other way. Let’s say you're looking at building a modest-ish 10 storey block of flats within one of the view cones, in an attempt to provide much-needed housing for Oxford. The City Council might be minded to approve it as an exception due to housing need. But planning is so reliant on case law that one “exception” like this would potentially undermine the entire policy across Oxford, irrevocably changing the whole skyline. (Not to mention the inevitable appeals to the Planning Inspectorate, and officer time defending or denying a flood of planning applications.)

For now, then, it looks like Oxford’s skyline is preserved in aspic. Perhaps ingenious architects can find a way (and some land) to build in between the view cones. Perhaps developers will continue to build up to the limit, as they do now.

Or perhaps an Oxford politician will be brave enough to follow Ken Livingstone (a Labour mayor, after all), and find a way of relaxing the view cones policy to allow higher development. Oxford is a living, breathing, and expanding city. Are the city’s electors happy that the clock has stopped? Is there a case for tweaking the less sensitive view cones to provide more housing?

History vs. housing. It's Hobson’s choice. Like much of what we’ll be covering this week, it’s a debate that Oxford is not yet having – but needs to. The Oxford Clarion isn’t here to recommend one course or another, but we know that among our followers and subscribers are some of the most knowledgeable and passionate people on this subject. Let us know your views: our city needs to have this conversation.

Enjoyed reading this? We are the Oxford Clarion: we write to inform and to shine a light on Oxford's democracy. This is the second in a five-part series, ‘Housing Week’, examining Oxford’s overheated housing market. Every Friday, we send out an email roundup of all the news we’ve found in the week, plus a few bonus extras. Hit the subscribe button and it's in your inbox, free. Exceptionally we're sending an email each day this week: we'll return to our regular Friday rhythm next week.

Further reading

- Tall Buildings Advice Note (Historic England) – how to plan tall buildings in a historic environment

- Oxford Views Study (Oxford City Council)

- Technical Advice Note 7, High Buildings (Oxford City Council)

- London View Management Framework – view cones in London

- The Protected Views of London (Stephen Liddell)

- How are protected views shaping cities (The Guardian, 2015)