Could you go car-free?

That was the question posed by local group Low Carbon Oxford North. Earlier this year, they appealed for 12 Oxford drivers to voluntarily give up their car for three weeks, and to report back on their experiences.

The 12 chosen were all long-term drivers, many reliant on cars since an early age. They were from all backgrounds and demographics: young and old, able-bodied and disabled, with and without children, and from different ethnicities.

This week, in conjunction with climate change charity Possible, the findings from the exercise were published. It’s a compelling insight into the challenges that must be overcome before Oxford can move away from the personal motor car.

Why go car-free?

Many of those involved in promoting sustainable travel are long-time converts – people who have been walking, cycling, or taking the bus for years now. But what factors might encourage a frequent driver to give up their car, even if just for a few weeks?

Most of the 12 drivers listed health and wellbeing as a top reason. Not just from the exercise involved in walking and cycling, but in reducing stress from sitting in congestion. In the words of one participant:

“If I'm in the car, I'm showing up to work, I'm stressed, I'm thinking about transport, I'm thinking about this car that's just cut me up on the A34, you know, these types of things.”

The second most popular reason was climate change. A couple of participants said that though their personal impact was small, they saw the benefit in being part of “a bigger movement for change”.

Oxford’s perennial congestion was inevitably mentioned. So too were transport costs, but more as curiosity rather than a definite conclusion – would it really be cheaper to buy bus tickets rather than running your own car?

And why not?

Convenience was the most frequently cited reason for using the car, especially when doing the supermarket shop or carrying heavy items. Those with young children or disabilities were particularly concerned that buses, bikes or walking would limit their options compared to the car.

Closely related was that all the participants simply had the driving habit: using a car was part of their routine and something they understood, whereas bus routes and safe cycling options weren't. Even among those who would consider cycling, safety was a major concern. Some participants wouldn't cycle at all for safety reasons: others were interested, but didn't believe the three-week project would give them enough time to learn cycling skills.

Safety issues weren't confined to cycling. Some female participants said they were worried about walking home after dark.

“If I was in my car, I wouldn't even give a second thought to what way I would go... So I need to think about what route I'm going to walk – are there street lights that way?”

So what happened?

Before the challenge started, the participants were asked to keep a travel diary to record their usual travel patterns. Then, for three weeks, they tried out alternatives to the private car: foot and bike, car clubs, bus and train. During this time, Low Carbon Oxford North volunteers supported them by offering advice, bike repairs, and so on.

Whether the exercise will have any lasting effect on the participants' travel habits remains to be seen. But for the three weeks, the report concludes, “most people had a very positive experience”. Participants reported better physical health; improved mental health; better connections with their neighbours and colleagues; and, significantly, happy children.

"My children are more excited about this experience because we walk so much and they stop in the parks to play… my children are enjoying this challenge even more than me. Their happiness is motivating me.”

“Instead of driving home and sitting in traffic for 20 minutes, getting more annoyed, I can walk home and it might take an hour, but I listened to an audio book whilst I'm walking and I get home. I feel really Zen. I feel great.”

“Oxford is a really beautiful city… and I just don't appreciate where I live. I walked home on Tuesday evening and I walked home through the park and I was able to see all of the bulbs coming up. It was great walking back.”

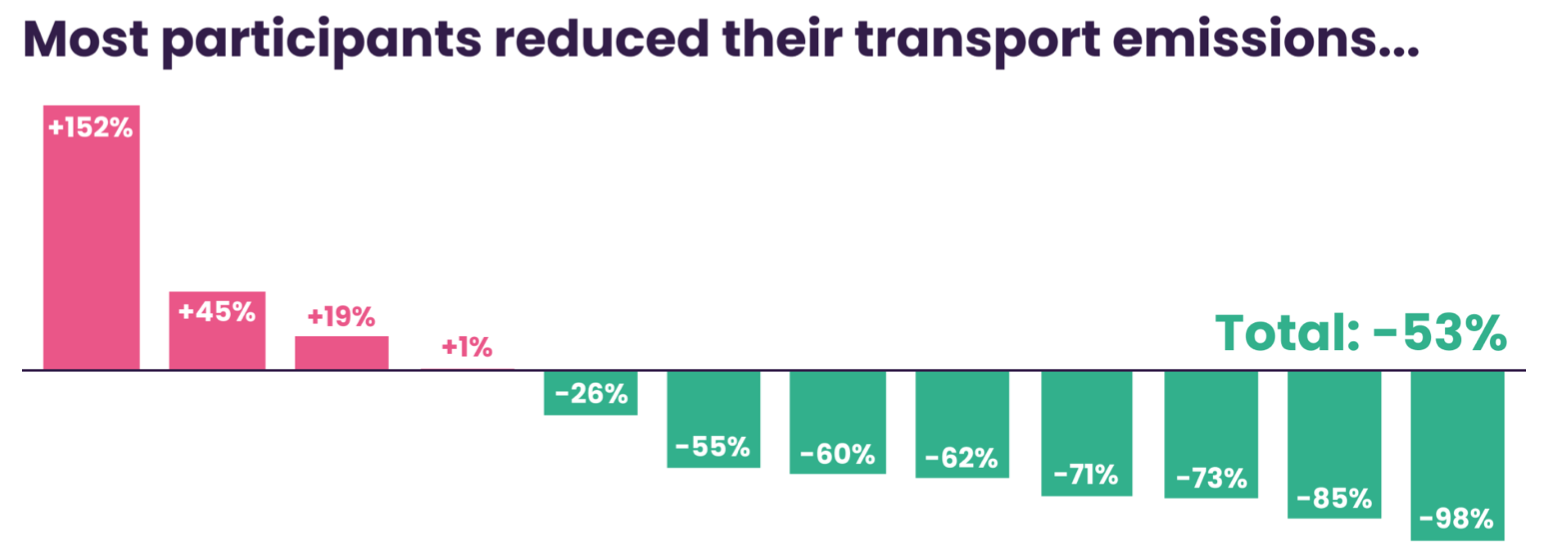

The participants also believed they were doing the right thing, not just for the planet, but for Oxford: one said they were keeping the roads clearer “for those who really need to use them, like the emergency services”. From a climate change perspective, the experiment clearly succeeded: totting up the journeys made, the total carbon saving was more than half.

What didn’t go so well?

After-school activities, particularly outside Oxford, were the biggest challenge. With no direct buses or safe cycle routes to get there, many participants resorted to taxis. Otherwise, they felt that they only needed to plan “a bit more” to make their non-car journeys – the biggest pain point being catching the bus in the morning.

For one of the two participants with reduced mobility, the experiment clearly didn't work. They said they found buses "slow, unreliable and frustrating", with basic problems such as slippy floors on the bus making their mobility aids dangerous. They said they were "frustrated, isolated, and less productive at work" as a result.

The jury remained out on affordability, particularly where trains were concerned. Train fares seemed expensive to people who already owned a car:

“I've already taxed the car for the whole year now and insured it. Once you get into that cycle of paying, it's kind of hard to get out of it – not using it then feels like a waste of money, or like you're not making the most of it.”

(The participants' average annual spend on their car was between £1,320 and £6,890.)

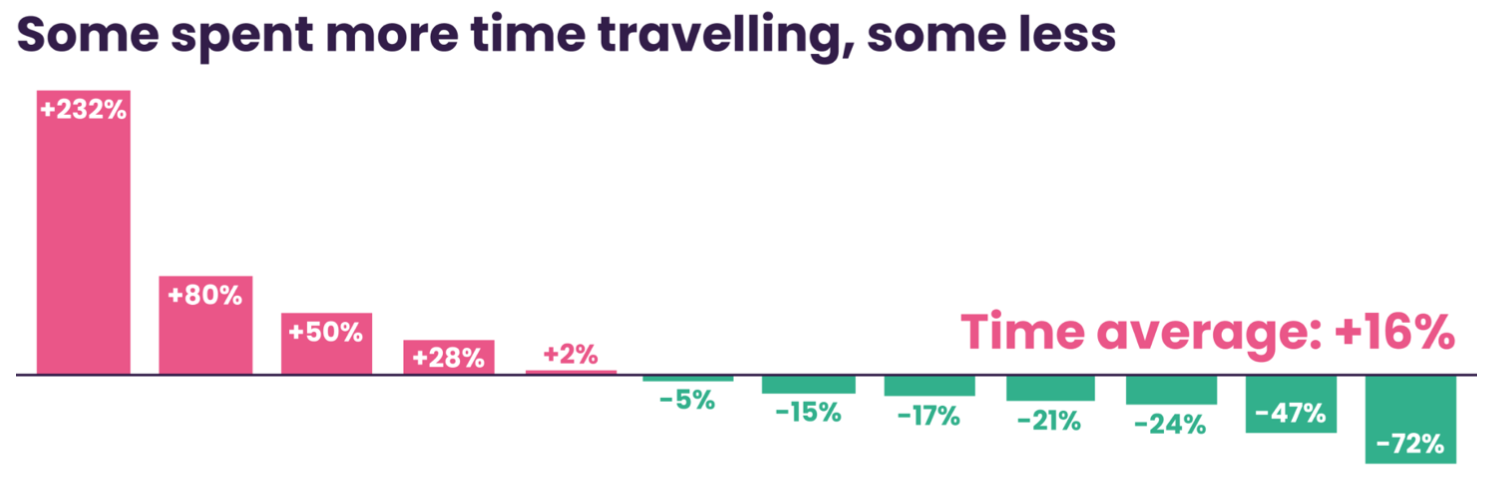

Averaged across all those taking part, there was a 16% rise in travelling time – but the average was significantly skewed by one participant for whom alternatives to the car were impractical. For the other 11, the average was actually a saving in travel time of 4%.

How did different types of transport compare?

Walking and cycling came out well in the participants' eyes. Not all could cycle, and not all trips were short enough to be walked, but several said they were "surprised and impressed" how easy they found it to cycle around the city.

Oxford's buses got a mixed reception, with participants slating them for being unreliable.

"Sometimes when you wait for the bus, my colleagues said the bus can say, ‘it will come in five minutes’. Five minutes would be like 10 minutes. 10 minutes would be like 20 minutes.”

“There was a couple of mornings where the bus didn't show up... that can really knock your reliance on it.”

They also noted that though there were plentiful buses into the city centre, journeys to other destinations either required changing buses or weren't possible at all. Instead, they'd take a taxi. Car clubs and taxis, they felt, could make sense financially as an alternative to owning a car.

Trains, meanwhile, were "fast and convenient" but expensive. One participant drove all the way to Durham because the train cost too much. (We looked up the cost of a turn-up-and-go return from Oxford to Durham. It’s £178 – or £381 if you have the effrontery to travel before 9.30am, which if you’re going to Durham, you probably will. We are not remotely surprised the participant drove.)

What needs to change?

At a distance of a few months, the experiment seems to have had positive results. 10 of the 12 said they would continue to drive less. One gave up their car entirely, and another said they may do so at its next MOT.

But the real value in the exercise is not so much the successes as the failures – identifying the barriers that prevent people choosing alternatives to the car.

Oxford's bus offering needs to shape up. We say “bus offering” because it’s not all in the control of the bus companies. Improving bus punctuality is the main driver behind the trial traffic filters, due to take effect this November.

There is also a planning aspect to this. Many leisure activities for kids take place out of town simply because equivalent facilities aren't available in Oxford. It's hard to make an activity centre pay the rent in the second most expensive city in Britain. (Though for kids of 7 and up, Team Clarion strongly recommends Didcot's Wave swimming pool, plus Clip'n'Climb and Jump Inc in Bicester – all just a short bike ride from the station.)

Cycle routes in Oxford are not safe enough to attract new cyclists. The on-road provision that dominates the city might work for existing cyclists, but the report highlights that newcomers need “dedicated, well-maintained cycle routes free from traffic”. Providing quiet routes via Low Traffic Neighbourhoods works for the school run, but for longer journeys, newcomers still have to brave intimidating areas like the Plain, the High, St Aldates and St Giles. Nor is the need for safe routes restricted to inner Oxford: supermarkets on the edge of town and county leisure facilities were particularly hard to reach.

The 12 participants benefited from one-on-one help from Low Carbon Oxford North. This help isn't available to everyone. Knowing which bus to catch, where the safer streets are, or how to change a bike tyre are genuine issues for people who would have no trouble telling you which M40 junction is which or how to top up screenwash. Oxford has well designed bus apps, and a clutch of remarkably helpful bike shops, but the learning curve can still be steep.

Low Carbon Oxford North says that “a relatively simple package of support measures could be effective in supporting a shift away from private car reliance”. This could include personal travel advice, motivation campaigns, and practical support such as bike servicing.

In particular, they suggest introducing “a support service for residents to get help and advice for car-free travel”. Key to this is a recognition of the right tool for the right job: a walk to the corner shop, a bike ride to school, a bus across town, a car club out to the countryside, a train trip to London. For example, Oxford has some great car club options – but would you know where to find them?

Finally, the experiment is evidence that a move away from private cars is feasible for most people – but not everyone. 10 out of 12 people said that they would drive less: that they were happier, healthier and more sociable. By contrast, one participant of restricted mobility said they were “frustrated, isolated, and less productive at work”. The challenge is to find a way forward that brings the benefits of sustainable travel to the 10 out of 12, while still enabling residents with restricted mobility to enjoy the life chances they do now.

Perhaps the most interesting comment was the driver who said they wanted to travel more by foot, bike and bus to make more space “for those who really need to use the roads”. If Oxford can recognise that road space is a finite resource to be shared, not hoarded, then we may be able to find a way out of congestion.