From Banbury Cake to Oxford Sauce

We fell down a rabbit hole reading about Oxford sausages.

“Rabbit hole” is itself an Oxford University phrase, of course. While perusing various archive recipes to find exactly what should go into an Oxford sausage, we discovered a cornucopia of city and county food, historic and modern. (Not including rabbits, curiously, although Oxford’s White Rabbit is of course a city institution with a national following.)

If you are a regular Clarion reader, this may not come as a surprise. Oxfordshire is a county of market towns; Chipping Norton's very name is derived from the Old English word ceapen, meaning ‘market’. (We wrote about Oxfordshire's deep history in markets in a long read last year.) But markets only happen where there is produce, and where there is produce there is good food. Let’s go!

Ride a cock horse to Banbury Cross

Let's start at the northern edge of the county, where Banbury has had a market since at least 1138.

Until recently, the town woke up to the scent of roasting coffee thanks to a General Foods/ Kraft factory. It controversially pivoted to packaging in 2023, but you will still be greeted by the scent of baking bread from Fine Lady Bakeries, or a waft of melting chocolate from Belgian couverture maker Barry Callebault.

But Banbury has a long food heritage. It is of course famous for Banbury cakes, the original recipe having been brought back to England during the Crusades. A Banbury cake is a spiced, currant-filled puff pastry, similar to Eccles cakes. Today's recipe is a closely-guarded secret, but the filling typically includes mixed peel, brown sugar, rum, and nutmeg. They are made by baker Philip Brown, whose family has been producing them for centuries. You can get them at Banbury Charter Market, at local stockists or online.

Banbury cheese was once one of the town's most prestigious exports (and is surely due a revival?) but survives as an insult in Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor:

You Banbury cheese!

Here, Bardolph is alluding to Abraham Slender’s… slender figure, echoing the proportions of the cheese. Shakespeare was born just up the road in Stratford-upon-Avon, and so could well have eaten Banbury cheese.

Head south with us – although we miss the snack stops we used to have at the canalside Pig Place, with its campsite, outdoor cafe, vintage vehicles, open air gigs, friendly pigs and bacon sandwiches, for it closed as a cafe as we published this – and bear west to Hook Norton with its brewery.

On the twelfth day of Christmas…

Oxfordshire is not short of modern real ale and craft breweries: Loose Cannon, Tap Social, Little Ox, Chadlington and many more. Hook Norton Brewery, however, is something special.

One of the few surviving family-owned breweries in the UK, it celebrated its 175th anniversary last year. John Harris started brewing in 1856, with the first tied pub purchased in 1859. The Pear Tree Inn at the end of the lane the site sits on was purchased in 1869, and is still tied to the brewery to this day.

The steam engine that used to power the Victorian tower brewery still functions, and can be seen on tours. Its beers are award winning, and generally only found locally as they restrict deliveries to within a 60-mile radius of the site. The pubs in Hook Norton itself are served by the brewery’s team of shire horses, just as they were in the beginning. The video below shows a day in the life of a shire horse, and you can see them at local events.

(Of course, if you are too far away to be reached by shire horse, you can support an Oxfordshire business and buy their beer online. Try the Old Hooky, or at Christmas, Twelve Days.)

We will skip Charlbury and Bloxham entirely, because although we found a reference to ‘Charlbury sponge’ and ‘Bloxham pudding’, we have drawn a frustrating blank on any more than that. Perhaps our readers may have more information?

Let us continue south through Chipping Norton, not stopping to look in any way at Diddly Squat Farm (our first ever long read) or even Daylesford. You don’t need us to tell you about these. Instead, we are going to Burford.

Who ate all the pies?

We are not sure what it is about Oxfordshire that requires two types of dried fruit filled pastries, but Burford is famous for the Lardy Cake.

A Banbury cake is made with an enriched yeasted dough and folded around a fruit filling. The Burford (or Cotswold) lardy cake is a yeasted dough enriched with pork lard, rolled and folded around sugar, dried fruit and mixed spices. You can buy them online from Burford’s own Huffkins.

Having eaten all the pies, we'll head in along the A40 towards the dreaming spires of Oxford and the delights of the Covered Market.

The box of delights that is the Oxford Cheese Company (images Roger Close)

The cheese stands alone

Oxford is not short of excellent cheese shops. There's the Jericho Cheese Company, on Little Clarendon Street with its sister store on Ship Street – itself possibly a food reference (‘ship’ for ‘sheep’, referring to a sheep market). But the OG is the Oxford Cheese Company which was started by a scion of French nobility, whose family has had a huge impact on Oxford's food scene.

In 1983 a French Baron, Robert Pouget de Saint Victor, and his friend Gerry Stevens opened a cheese shop in Oxford’s Covered Market. Robert Pouget went on to form the Oxford Cheese Company which not only ran this cheese shop but began to supply English and continental cheese to Oxford colleges and city restaurants.

In 1995, Pouget began production of Oxford Blue, a Stilton-like cheese which has since become one of the most popular blue cheeses in England. Since then the Oxford Cheese Company’s brands have mushroomed, selling local honey, oatcakes, Hook Norton Beer-accented chutney, and a host of new cheeses including Oxford Isis (a pungent soft cheese whose rind is washed in mead). But their most successful spinoff is Oxford Sauce. Created in 2000 to celebrate the millennium, it doesn’t really bear much relation to the Cumberland-style Oxford Sauce of the 18th century, but was conceived for today’s rather spicier palates. (You can, of course, buy all of these items online, even in tuck box form.)

These days Baron Pouget divides his time between Oxford, where the cheese and chutney business continues to thrive, and Cornwall, where he devotes his time to painting. Meanwhile, another part of the family has an Oxford café empire: William Pouget’s Alpha Bar whole-food takeaway in the Covered Market, the Vaults and Gardens Cafe in Radcliffe Square, Chickpea in King Edward Street and Salsa del Sol on the High Street.

Although the Covered Market is more of an all-round visitor destination than a produce market these days, the last remaining butcher, David John, will sell you some Oxford sausages (if you can make it past the tempting display of pies in the window). Again, you can also buy online.

But what is an Oxford sausage? Who better to explain it than the Oxford Sausage blog:

The recipe for what became known as the ‘Oxford Sausage’ is credited to Dorothy Spreadbury who lived in the early 1700s. Originally made from pork, veal and highly spiced with lemon and herbs, they were soon being cleverly marketed by her niece Sarah Herbert, who sold them, cooked as a snack from her husband’s watchmaker’s shop on the High Street. Positioned next to The Angel Inn, a major station for coaches travelling to and from London, they were a sizzling success. By the time the Covered Market opened, everybody was making them; when Mrs Beeton called them her ‘ideal sausage’ and featured them in her book of ‘Household Management’ in 1861, they became a phenomenon, synonymous with the city itself. On being asked at a parliamentary committee in the 1880’s if there was anything manufactured in Oxford, a city Alderman replied, “we have two, parsons and sausages!”

(The Oxford Sausage blog features regularly in our newsletters; we encourage you to read their review of David John, and the reproduction of Mrs Beaton's recipe for the Oxford Sausage.)

Georgie Porgie, pudding and pie

Let's stay in the city centre a while longer. Look at the dreaming spires of the colleges. Those colleges, over the centuries, have developed quirky foodie traditions all of their own.

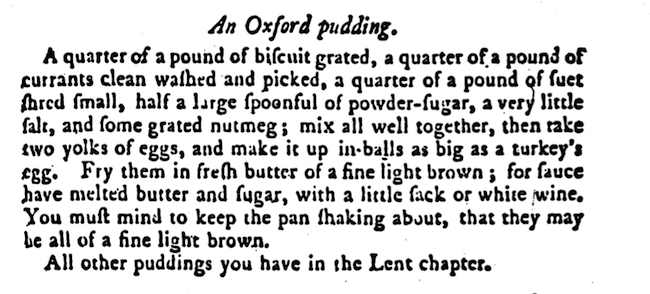

New College Pudding is a dough made of breadcrumbs, dried fruit, suet and sherry, and then shaped and deep fried in butter. It first appeared in The Compleat Housewife by E. Smith, published in 1736. But just a decade later, we find the suspiciously similar Oxford Pudding in one of the first blockbuster cookbooks, Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cookery – published in 1747 and a bestseller for more than a century after. In 1747 there were 21 Oxford colleges vs the 43 there are now. Perhaps the upstart New College, ‘only’ started in 1379 (vs the original University College of 1249), had a disproportionate culinary fame in the city?

Members of New College still gather to drink Mint Julep every 1st June . The cocktail, containing bourbon, brandy and mint, is provided thanks to an endowment left to the college by William Heyward Trapier of Windsor Plantation, Georgetown County, South Carolina. Having visited in 1845, and been unable to procure the classic cocktail of the American South, he left money to ensure that each year, those dining in halls could receive a free mint julep. As with many alumni donations from the USA, questions have been raised over the source of the funding; the plantation in question was successful due to slave labour.

But at least disagreements over this drink have not yet escalated to rioting. In 1355, a riot began started when two students complained about the quality of wine served to them in the Swindlestock Tavern at Carfax. By the end of it, 93 people were dead across town and gown. Booze was important enough to fight over.

It is therefore not that surprising that Oxford is the source of the first ever cocktail book, 1827’s Oxford Nightcaps (‘Being a Collection of Receipts for Making Various Beverages used in the University’). The most famous recipe is the Oxford Bishop or ‘smoking bishop’, a spiced mulled port referenced in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. It's been translated into a more modern, chilled version that's no less festive.

“A merry Christmas, Bob!” said Scrooge, with an earnestness that could not be mistaken, as he clapped him on the back. “A merrier Christmas, Bob, my good fellow, than I have given you, for many a year! I’ll raise your salary, and endeavour to assist your struggling family, and we will discuss your affairs this very afternoon, over a Christmas bowl of smoking bishop, Bob!”

Oxford Nightcaps also references a ‘cardinal’ and a ‘pope’ version which “owe their origin to some Brasenose Bacchanalians”. We rather hope today’s Oxford Catholics celebrated the white smoke ascending, to signal the appointment of Pope Leo XIV, with a smoking bishop.

We could continue with the roast Boar's Head served at Queens College every Christmas dinner, to commemorate a quick-thinking student at Shotover who, on being attacked by a wild boar, thrust his copy of Aristotle's Logic into the beast's jaws, whereupon it choked to death. Or we could look at Magdalen venison (they do have a deer park) . Should you need it, you can purchase a volume of the College Graces of Oxford and Cambridge in the Bodleian Shop, if you're tempted to do a full recreation at home.

Vintage marmalade (Flickr, Jason Tabarias CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) and the soft play version (Oxford City Council)

Oranges and lemons, say the bells of St Clements

Marmalade is so synonymous with Oxford that, when Oxford City Council unveiled a new soft play recently, they included a replica jar of Cooper's Oxford Marmalade in their tiny Covered Market. [Your Clarion scribe could not love this any more. Well done Oxford City!]

Frank Cooper was an Oxford shopkeeper with premises on the High Street. The first batch of this now famous marmalade was made by his wife, Sarah Jane Cooper, in the family kitchen in 1874. It was originally sold mainly to Oxford dons and colleges, but sales expanded dramatically when production moved to a factory on Park End Street. (In latter years this became a bar, cafe and arts venue, the Jam Factory.)

The Museum of Oxford hosts a collection of Cooper memorabilia including a tin of marmalade that made it to the Antarctic on Robert Falcon Scott's ill-fated expedition to the South Pole. For the second time in this article, we will direct you to the glorious writing of the Oxford Sausage for a deeper back story on the sweeter side of Oxford.

The butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker

Oxford’s culinary evolution didn’t stop in the 19th century. One of the city’s most beloved food institutions is rather more recent.

In the summer of 1992, George Stroup, an Oxford student, opened George & Davis on Little Clarendon Street. George & Davis became affectionately known as “G&D’s” and has thrived, opening two more shops (George & Danver opposite Christ Church, George & Delila on the Cowley Road). The ice cream is made by hand in Little Clarendon Street with fresh, local ingredients and a rotating flavour range from classic vanilla to quirky (Guinness sorbet anyone?), then delivered by bike to the other shops. There are full-size tubs to stash in your freezer for a midnight snack attack, and for some reason, excellent bagels too.

The city’s gastropub boom has meant it’s easier to eat well now than ever. But putting the claims of the Covered Market and Gloucester Green to one side, Oxford’s gastronomic centre of gravity has arguably shifted east to the Cowley Road and its offshoot Magdalen Road.

Here, you can buy food from all corners of the globe. If you're new in town or visiting, book a space on the monthly food tour. If you just like mooching (or mochi), anything can be found. Korean? Try Seoul Plaza for kimchi and snacks. Turkish? Erdem, at the other end of the road, for vats of hummus, tinned cheese, wholesale quantities of rice and spice. Brazilian? JGs for frozen churros, açai, epic meat and cans of sweet stout. Traditional butchers? Alder's. Italian? Il Principe (wine, pasta, antipasti, frozen tiramisu… you know you want to). Patisserie? Millefeuille. Eastern European? Baltic Food for herring, vareniki, vodka, smetana, and pickles. Just go. Shop hard and come back soon.

(We need to write a long read on this, clearly. Just for the sheer joy of investigating it. But until then, for cafe and restaurant reviews, check out the excellent Bitten Oxford who have noses for the best eats in this part of town.)

We would make a turn north towards South Park for Oxford's artisan spirits producer TOAD, now Fielden, but the distillery has been mothballed and production exiled to Hull. Just before Christmas, Oxford City Council completed a tender process for the site. They say a bidder has been selected and the legal process begun, with an announcement expected at the end of the summer. Could the stills be resurrected?

If you're on a bike head south to Abingdon along National Cycle Route 5, and stop in at the brilliant Proof Social Bakehouse, in an industrial estate in Sandford. Part of Tap Social Movement, it's a social enterprise offering paid training and employment to people currently serving or recently released from prison sentences. The tagline is “criminally good bakes” and it’s not wrong. Go there for the cinnamon rolls, or the bread, the excellent coffee, or the buzzy atmosphere (especially if you like meeting dogs). Then head south to Abingdon because we will finish with a grand finale, a glorious tradition that embodies the very definition of English eccentricity…

One a penny, two a penny…

Should you be in Abingdon on the day of a royal wedding, or perhaps a coronation, you might be able to catch a flying bun.

Rooted in a tradition of giving bread to the poor, Abingdon marks national occasions by having civic officials throw currant buns from the top of the tower at the Old County Hall down at the people of Abingdon. The tradition dates back to 1761 and the coronation of George III. There is an entire website dedicated to bun throwing (and even a Wikipedia page), but the video below gives you a sense.

Beer and buns, cheese and cakes, sausages and sauce, marmalade and mint julep. All from a place whose very name – Oxen ford – recalls the drovers taking their cattle to market. In an age where we’re encouraged to eat local, consider food miles, and think about the provenance of what’s on our plate, it’s not a bad county to do it in.