How the election count works

They call me the Count because I really love to count.... ha ha ha ha!

We are not (quite) delirious with election fever. But the campaign is entering its closing stages. Soon, it’s all over… bar the counting.

If Britain is a beacon for democracy, and the UK parliament is the “Mother of Parliaments”, then the process by which our MPs are elected must be watertight. In this latest long read, we set out what happens once you have cast your vote. Maybe you might want to stand for Parliament, or just your local council, one day?

Clarion writers have, in other guises, attended counts and found newcomers baffled and sometimes mistrusting of the process – seemingly expecting to see bundles of ballot papers disappear. Here we set out what happens, here in Oxfordshire and across the country.

The venue

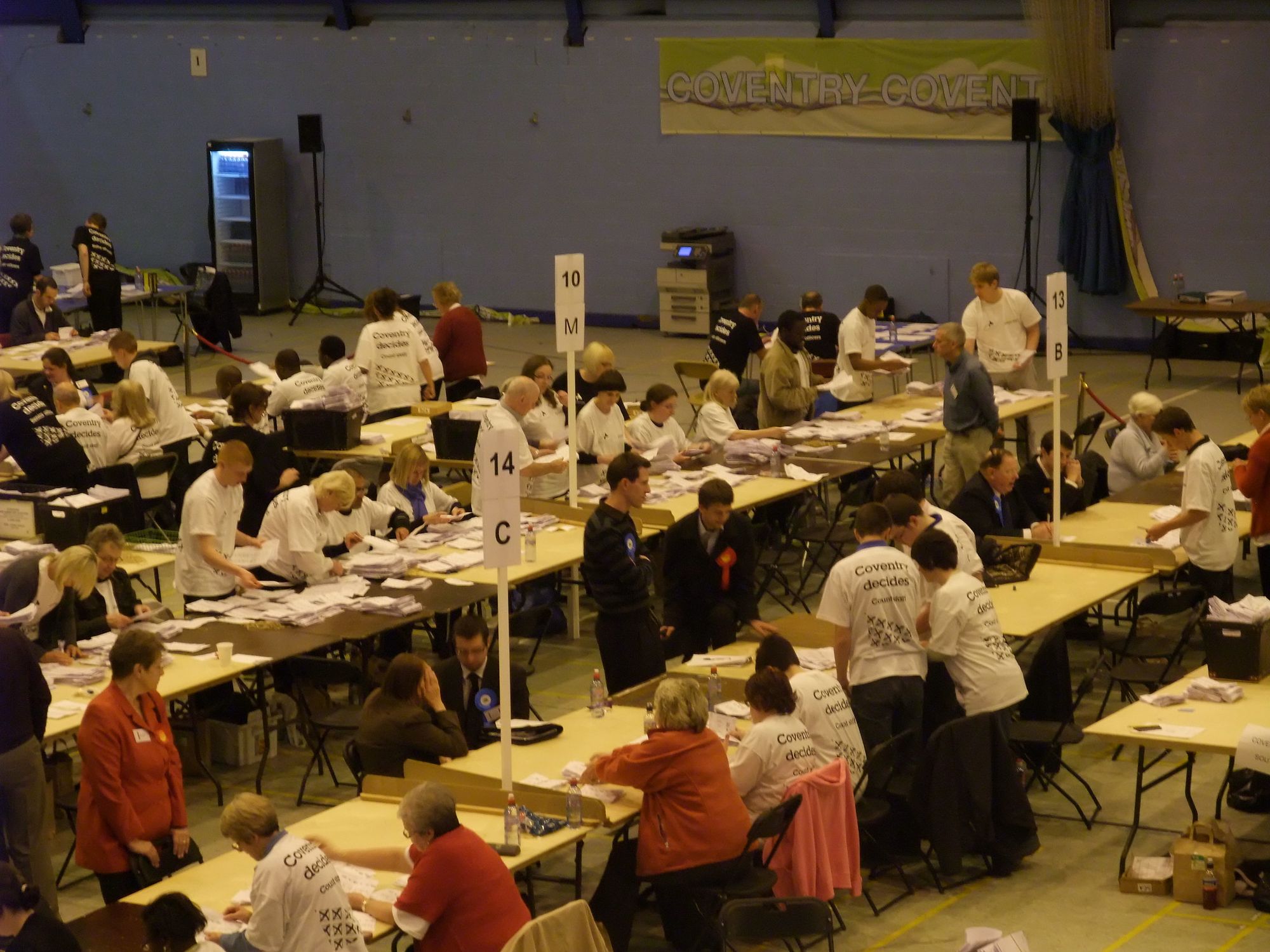

The counts are organised by city/district councils. Oxford City Council runs the Oxford East count, and as such gets to use its own storied location, Oxford Town Hall – though in 2019 a diary clash meant it moved across the road to St Aldate’s Church. The counts for Oxford West & Abingdon and the county seats usually take place in each principal town’s leisure centre: more pragmatic, less photogenic.

The votes arrive at the count in ballot boxes from the polling station. They have been watched over the whole time. The parliamentary election is always counted that night, but local elections will sometimes be left to the day after, perhaps to give staff that have been manning polling stations a chance to rest before counting. In that situation, the boxes will be watched by a security guard to ensure no tampering and that the seals remain intact.

Verification

Each ballot box represents one polling district. When you were casting your vote, your name was checked off the electoral register, to make sure you couldn’t vote twice. This becomes the ‘marked register’. That marked register, by virtue of being marked, now contains the amount of votes cast. This is counted. The total is critical: the number of ballot papers must match the number of votes cast in the electoral register.

The count room is divided into tables – counting stations, if you like. Each station will be assigned a polling district, or possibly more than one, counted sequentially. The ballot boxes which have been watched at all times are unsealed and opened. The piles of ballot papers are emptied onto the tables.

The first thing to do is to unfold the papers and place them, the right way up, into piles. The piles are then counted into tens, with a paper clip to mark the tens. Ten piles of ten are combined into hundreds, and then ten hundreds are combined to make a thousand.

While all this sorting of piles is going on, rosetted local party activists (“accredited electoral observers”) are fiercely scrutinising the ballot papers from the other side of the table. Why? Because this polling district level is the lowest level of granularity activists will see. Perhaps activists focused on a particular area around a school, or reckon their message landed well in some areas but not others? This is where you get a first litmus test of the way the results might go – and that informs where to target future efforts. By eyeballing the ballots as they are sorted and laid in a pile you can roughly see where the votes have landed.

The more organised local parties will have formal verification sheets to keep tabs on the candidates. More scrappy outfits will have notebooks and simple tally charts. This sounds simpler than it is. Usually the activists counting are the same people who have been knocking on doors all day (week? month?). They are sleep -deprived, and have to keep an eye on often several counting agents turning over piles of paper at once – oh, and contend with other counting agents from other parties who also want to be able to see the ballot papers easily.

In a hostile election, sharp elbows are required to mark your space. In a more collaborative environment, parties co-operate to ensure everyone can see something at least. People standing about and nattering/distracting the activists – or simply soaking up the atmosphere, as new candidates are perfectly entitled to do – are distinctly unpopular.

Once all the votes are sorted in this way the total is tallied. This tally must match with the number of votes crossed off on the marked register. If it does not, a recount will be ordered by the returning officer.

The votes are totted up by polling district to get a turnout figure. Again, the number of ballot papers at each stage must match the number of votes cast on the marked register. At the end of this stage, you have a verified number of votes. It’s still just a big pile of paper, but now they are all the right way up.

Vote Separation

The count agents now begin the count. They start by taking those big piles of paper. Then they separate the votes, putting candidates’ piles in relevant boxes. Party activists are still scrutinising the ballot papers. They aren’t counting any more.

The activists’ new job is to make sure that the right votes go in to the right piles. Well, in theory. Let’s say you are a Labour activist and you see a Conservative vote going in to your candidate’s pile. You may not be entirely concerned by this. A sensible activist will stand next to their opponent’s piles and make sure none of their candidates’ votes go to the opposition.

A table separates activists and counting agents, and ne’er the twain shall meet. It is absolutely forbidden for an activist to touch the ballot papers at any point. Even if someone accidentally knocked the table over, activists still cannot touch the ballot papers. If this were to happen, verification might need to be repeated: the number of ballot papers must continue to match the marked register.

Counting

The candidates’ votes are piled up. At this point, activists often have a sense of the result based on the size of the piles, and there may be a palpable sense of anticipation and/or panic.

The votes now need to be counted. They’re counted into tens; the tens are combined into hundreds; and the hundreds into thousands.

At this point, it is usually the wee small hours of the morning. Mistakes can happen. The counting officers have often been on a polling station all day and are also tired. Mistakes happen.

Good activists and good counting agents understand this and work together to ensure a fair election. Activists watch the count to make sure the piles of 10 are not 9 or 11; and that the piles of 100 contain 10 piles of 10 votes; and so on. Once again, the total votes must match the count on the marked registers.

Spoiled ballots

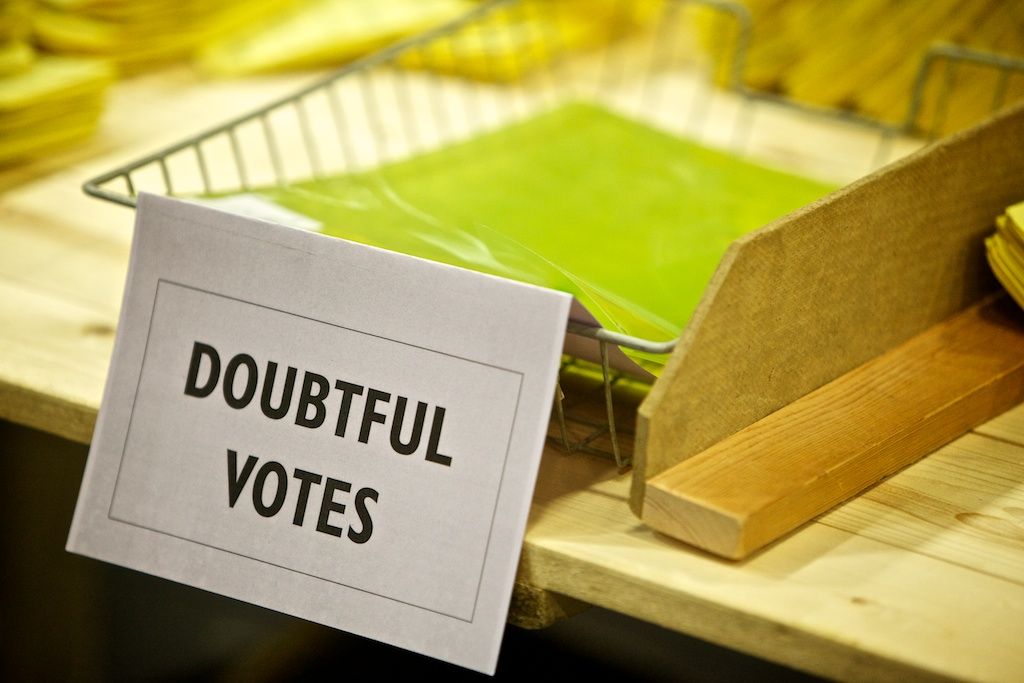

Spoiled ballots or doubtful votes may be a source of entertainment in a race that isn’t close, or a bone of contention if it is. If the intention of the vote is clear, it doesn’t need to be checked and is counted in – although candidates and agents may prefer otherwise.

Ultimately this is the Returning Officer's decision. For example, say someone votes for an independent, but scrawls “Mainstream politicians are a bunch of tossers” on the paper. The intention of the vote is clear: the independent gets the vote. Or perhaps there’s a dot in the Green box (or a vote is crossed out) and then a big cross in the Labour box – that's a pretty clear intention to vote for Labour, and someone simply made a mistake in the polling booth.

However, if a voter crosses all the boxes and writes “you're all the same”, that becomes a doubtful vote and will go in that pile. This is then referred upward, and all doubtful votes are considered. The team boss and the returning officer make a recommendation on anything borderline, and all candidates and agents must agree on what the borderline vote is trying to say.

(Remember, your ballot paper is invalidated if you identify yourself in any way – e.g. by signing your ballot paper – or if you don’t make it clear which person you want to vote for. It is illegal to take a photograph of your ballot paper or anyone else’s ballot paper. This includes postal votes, so don’t post your postal vote on social media. Just do a selfie of posting it.)

Once candidates and agents have agreed on the doubtful votes, adding these to the tally will give a provisional result. Once more, the number of votes here must match the tally on the marked register.

At this point, if it is close, candidates and agents may request a recount. After all, mistakes do happen and by now it is quite late. People may be snappy. If it’s a parliamentary election, jobs, livelihoods and futures are on the line. It can be helpful for candidates and agents to agree in advance what the margin of error is for a recount (say, 10%) – otherwise, emotions may come in to play once the provisional total is announced and it’s close.

The recounts can go on for several rounds, following the same process. The count must match the register. The most likely source of errors are piles of 9 or 11 instead of 10, or the piles of 10s making it into hundreds not being correct. If two recounts return the same result, the Returning Officer can refuse a further recount. In the event of a tie, the returning officer must draw lots.

By this stage, candidates and their agents know the result (though will not have told anyone else); the activists have guessed it thanks to verification and counting observations; and the rest is a formality. Those announcements you see on TV? Not a surprise to anyone except the audience and the broadcasters.

Declaration

It’s the very small hours. In 2019, Oxfordshire’s seats declared between 3am and 6am. The moment of truth.

The cameras now pan up to the stage. The returning officer declares the number of votes cast, and the number of votes for each candidate – announced in the order they appear on the ballot paper – and the party they stand for. Cue cheers from the room from each party in turn.

This is a nervy time for the Returning Officer. If they announce the wrong result or allocate the wrong number of votes to the wrong person all hell breaks loose. Even if the error is immediately obvious, the result can only be overturned in court – as in this recent example in Banbury.

In district and county elections the candidates don’t usually give speeches. In Parliamentary elections they do, and the winner usually speaks last. TV news will, of course, have a camera crew at the most high profile counts: Rishi Sunak in Richmond & Northallerton, Keir Starmer in Holborn & St Pancras, but also key swing seats this time such as Bristol Central and Ashfield. Will any of Oxfordshire’s seats attract the cameras? We think Henley & Thame might, as an emblematic ‘Blue Wall’ constituency and Boris Johnson’s former redoubt.

The winner is, in the famous phrase, “duly elected”. But they don’t formally become an MP until they sign the paperwork accepting their election. Famously, Sinn Fein’s candidates are regularly elected to Westminster but never take their seats.

As we’ve laid out here, the count is a complex and painstaking operation – as it should be. Anyone who’s stayed up for an election will appreciate the military precision of Sunderland and its neighbours as they vie to be the first to declare, usually coming in before midnight.

Oxfordshire’s counts are less hurried, but no less professional. When you see a result flash up on the on-screen graphics or scroll into your Twitter feed, only to be supplanted by three more in the next minute, spare a thought for everything that’s taken place behind the scenes to bring you this.