Nium: a new chemical romance?

Featured in Dickens and even Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, our familiarity with ammonia may be through the pungency of smelling salts wafted under a nose.

But now we have roused you to alertness, we’ll tell you why it is one of the most important chemicals in the world, and about an Oxfordshire company called Nium that is aiming to change the massive 100-year old industry producing it, making a big dent in its climate impacts. (That’s important, but you can check our climate change history and science primer.)

It’s a gas

Ammonia is a gas with a past and a future captured in its chemical formula: NH3 – one atom nitrogen and three of hydrogen. Its starts with the nitrogen, which leads to it being the basic component of the most popular chemical fertilisers. If you did chemistry at school, you might recall the ‘Haber-Bosch process’; this combines nitrogen with hydrogen under high pressure and temperature, in the presence of an iron catalyst, to create ammonia. The process was simple, effective and if they were here today they’d call it massively scalable, because it now produces fertiliser for about half the world’s food. But it has a dark side, two in fact – and ones that Nium hopes to change.

The clue to the first is “high pressure and high temperature”. Ammonia production is highly energy-intensive. That makes it costly, and depending on how the energy is sourced, a substantial contributor to climate change.

The second is that most of the hydrogen for ammonia production has come from fossil methane. Here we apologise for continuing the chemistry lesson, but taking hydrogen from methane (CH4) leaves you with carbon, and if you don’t do anything else, this forms carbon dioxide. In total, it’s enough that ammonia production causes about 1.8% of total global greenhouse gas emissions.

Black powder

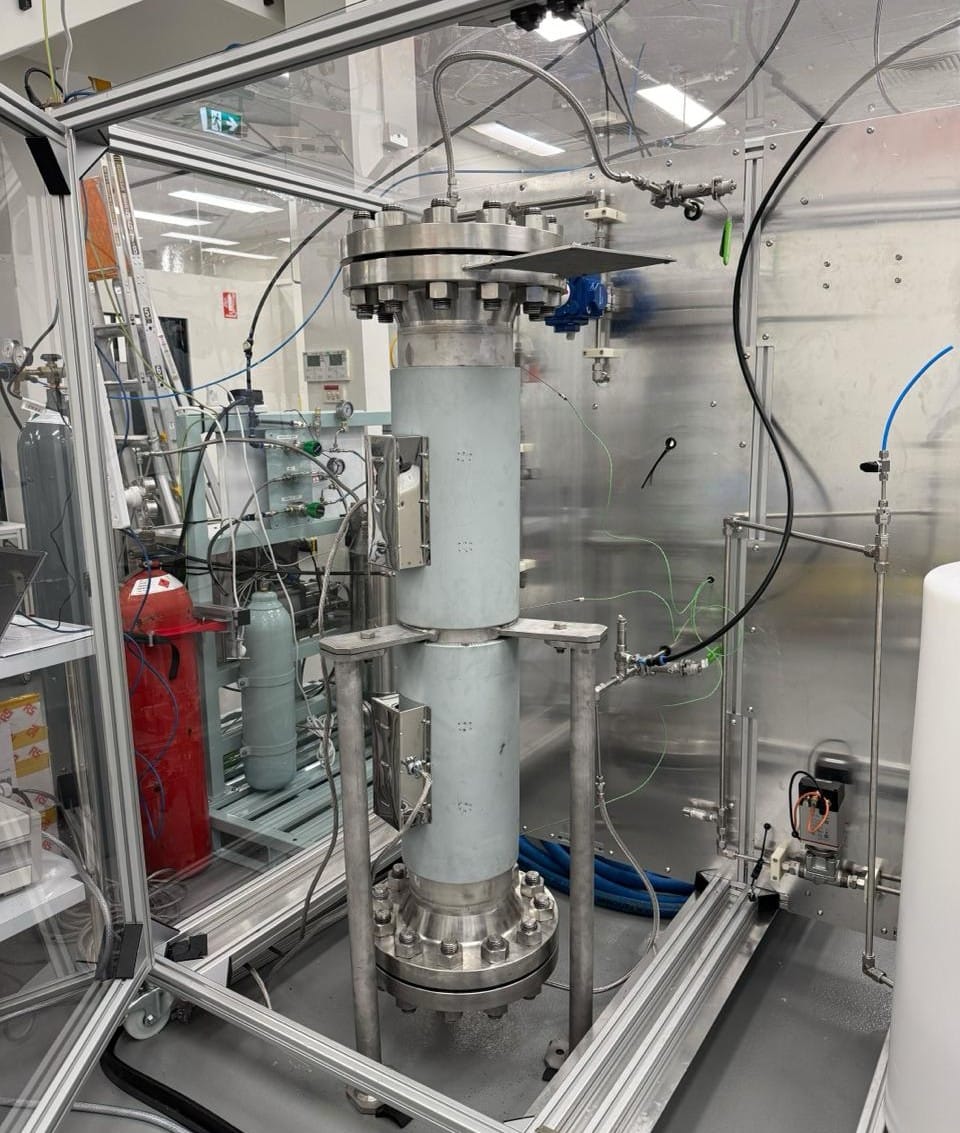

All this brings us to a typical-looking plastic-cladding and glass light industrial unit on Milton Park, just outside Didcot. Inside is new company Nium, and we get to see a little test tube of their new catalyst, formed of nanoparticles. It looks like a black powder, but it performs chemical magic. This catalyst allows the nitrogen + hydrogen = ammonia reaction to happen at lower temperatures and pressures, which is a huge saving in energy – solving problem one. They’ve tested in the lab, and have recently taken delivery of a unit that will allow them to produce and test much more of the catalyst. CEO Phil Hunter describes the old and new processes.

“Traditional ammonia production uses steam to split the methane and power the compression to about 200 atmospheres – it’s very energy-intensive, and even if you could get green hydrogen, you’d still need a lot of energy for the compression.

“Our catalyst is more active and it can make ammonia at 30-50 atmospheres and lower temperatures, so the amount of energy required is much lower. We can take nitrogen from the air by cooling, make hydrogen from water by electrolysis, combine the two into ammonia, power and the whole process with renewable electricity. The whole process fits into a unit the size of a freezer and we can scale it up to a shipping container or bigger depending on the energy available and ammonia required.”

Nium’s concept is to build modular ammonia production facilities that can be sited wherever there is excess hydrogen or the energy to create it, something that is difficult with the industrial Haber-Bosch process. Units built into shipping containers with an air separator and 10 catalyst-containing ammonia reactors could be sited near solar farms, wind farm connections or even nuclear power stations to harvest spare electricity and make ammonia, which is easily stored.

As more ‘green hydrogen’ becomes available from splitting water with clean electricity, this begins to address problem two – replacing methane-sourced ammonia with green hydrogen-sourced ammonia.

Fuel the world

As solar energy gets ever cheaper and wind energy is getting more plentiful, scientists have been looking for ways to store spare power on sunny or windy days. Batteries work for small amounts, but are very expensive on large scales. Splitting water and storing hydrogen is one candidate, but it turns out that hydrogen is very difficult to store and transport – its tiny molecules tend to seep out through the tiniest gaps in any pipe or container, just like a helium party balloon will go down faster than an air-filled one.

Happily, ammonia is a great way to store and transport the energy in hydrogen. Lightly chilled to its liquid form (-34 °C), you can pack three times the energy in the same space by using ammonia rather than hydrogen. While it’s not quite as good as petrol, it contains many times more power per kilogram than lithium batteries – and while batteries are proving viable for cars and even short-range flying taxis, they are proving difficult for heavy lorries, long-distance coaches and larger aircraft. That’s where an alternative fuel like ammonia could step in.

As with many good ideas, this has been thought of before. a fleet of ammonia-powered buses operated in Brussels during World War II to circumvent fuel shortages.

Adding up to impact

Many technology start-up businesses struggle in the journey from lab to production. The gulf between investing money to create a saleable product and earning from it to sustain the business has become known as the ‘valley of death’ after the shape of countless cashflow charts.

Nium has been fortunate in its funding. It was backed initially by Carbon 13, a climate-focused start-up programme based in Cambridge – similar programmes exist in many industries across the country. Further funding came from public agency Innovate UK, venture capital investors AgFunder and DCVC.

In the words of Phil Hunter:

“We were fortunate to raise initial funding in 2022-23 when cleantech funding was strong and we’ve been very successful with grant funding. It’s now a lot harder for cleantech and the focus is on AI, but we still need to be working on these paradigm shifting technologies. We’re looking to raise more to scale-up, but looking for collaboration as well as finance so we can link in with energy and agriculture partners.”

If Nium’s trials are successful, it could trigger a revolution in ammonia production, reducing the costs and climate emissions of fertiliser. Or it could make ammonia into a practical fuel – a scientific review in 2024 reported on potential applications in road vehicles, shops and aircraft. Or both.

All this could be starting from a nondescript light industrial unit just outside Didcot. One wonders what is happening in the hundred or so others that surround it on Milton Park.

Our business and technology correspondent is always keen to tell the stories of innovative and exciting Oxfordshire businesses that are doing good for the world (and frankly, we enjoy looking behind the scenes). Know of an Oxfordshire success story we should be covering? Drop us a line at news@oxfordclarion.uk.