OUFC’s new stadium: what do the consultation responses say?

“If you don’t want to know the scores, look away now.”

The planning application for Oxford United’s new stadium at the Triangle, near Kidlington, is open for consultation. Responses are still being received, but at the time of going to press – not yet full time, but well into the second half – the score was 398 in support, 42 against.

As aficionados of Oxford traffic issues will know, consultations are not referendums. If 4000 people write in support of an application, but there’s one compelling reason in planning law to refuse a development, then the development doesn’t go ahead.

That said, elected politicians and officials alike respond to popular support. If OUFC can demonstrate widespread support for the new stadium, the two councils are more likely to work with them to overcome any contentious issues.

It so happens that this is an important election year. Cherwell District Council, the council which will determine the planning application, is currently ‘hung’ with the three main parties eager to gain a commanding position in May’s elections. There’s a general election coming up, too, and the stadium will be a major issue in the new Bicester & Woodstock constituency which includes Kidlington.

So the decision-makers of Oxfordshire will be reading the consultation responses carefully to gauge public support. We decided to do the same, but with added data science. We have analysed the most common themes in the 440 individual responses received to date.

What supporters say

The word cloud for the near-400 responses in support is startling. One word leaps out: “community”. Close behind are “public” and “transport”. You would have to squint to find “league”, “promotion” or “pitch”. Supporters are keen to stress that for many of them, OUFC isn’t just a weekend recreation, but a community.

“If the new stadium does not happen, this community will be killed off alongside our club. Some people will lose not only their identity, but some of their only contact with other people. Some of the older supporters don't go out and socialise much other than coming to the football. It builds bonds between different generations.”

“I took my son to his first game 20 years ago when he was 5 years old. We are still going together now, it's something we both really look forward to. When we get to the ground we meet up with friends, friends who we would rarely see if it wasn't for football.”

“I am 54 and have been an OUFC season ticket holder all my adult life, and now go occasionally with my grown up children and my grandchildren also. It really is a family feel at the club, more now than ever.”

“The real value of the scheme is the positive impact it will have on the community. It will provide a community hub to inspire young people, lead the way in health promotion, provide local jobs and investment, and to provide world class facilities that reflect Oxfordshire's world renowned image and reputation for innovation.”

Several supporters pre-emptively defended fans’ reputation, though in fact only a minority of objectors raised this:

“A lot of the objections you will receive will focus on anti-social behaviour. I have been attending Oxford United matches for 25 years and I can tell you with absolute certainty that the vast, vast, vast majority of people attending are families with small children, older people, and young professionals.”

There was not much love lost for the Kassam Stadium:

“I first went to the Manor Ground with my Dad in 1963 to see Oxford United. I loved the colour, the excitement and the atmosphere of the games played and have been a fan ever since. My family had season tickets at the Kassam Stadium but gave them up due to the lack of atmosphere, the dilapidated state of the facilities and difficulty parking. The stadium never ever felt like a home to the club and they deserved so much better.”

Supporters generally felt that traffic issues were overstated:

“Concerns about traffic can be managed as they are at stadiums around the UK every week where temporary road closures are commonplace. Road closures will only be very occasionally needed at off peak traffic times: the vast majority of OUFC games are played at 3pm on a Saturday afternoon or 7.45pm on a Tuesday evening, every other week.”

“The surrounding roads, at the time the stadium would operate are currently the quietest of the week, Saturday pm, and the occasional Tuesday night game, great! The train station just a stone’s throw away, great! Many park and rides locally! A very underused Frieze Way!”

“The impact on roads immediately after football matches is usually extremely brief - recently we attended a match at Coventry where the attendance was over 18,000 - with some light traffic management from marshals that kept both the traffic and the supporters moving, the ground was cleared in around 20 minutes.”

Many pledged to use public transport to reach the site:

“It will allow me to get to matches without having to use my car which is currently impossible.”

“The plans for the new ground, just minutes from a train station, will transform my matchday routine, enabling me to use public transport and leave the car at home.”

“I like to travel from my home to games via the train, and having a stadium next to a railway station is a really good idea. As it stands, we face a nearly hour long journey down Cowley Road to games.”

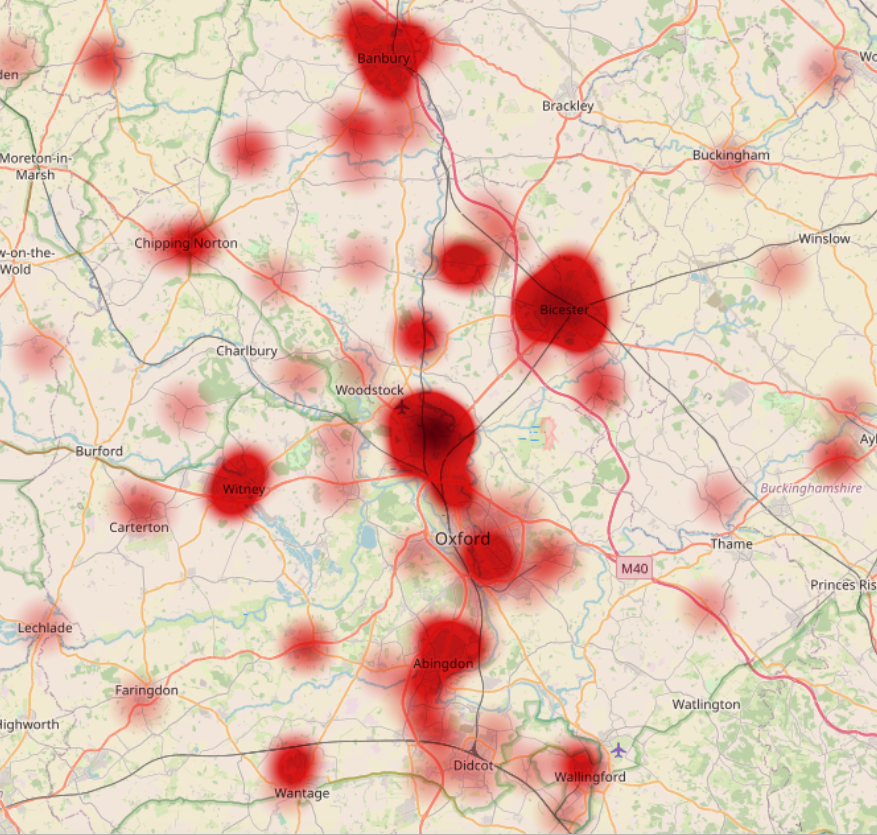

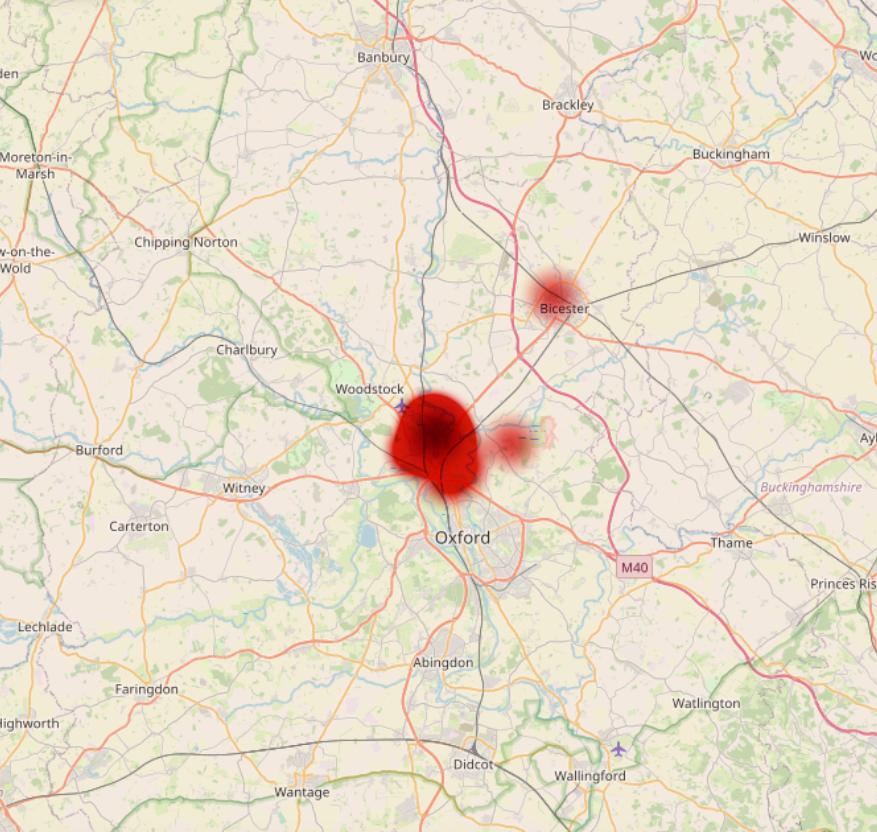

As well as the word cloud, we also calculated a heatmap of where those writing in support live. They are scattered around the county, but the highest concentration is in Kidlington itself. There are also clusters in the market towns of Bicester, Banbury, Witney and Abingdon – but fewer respondents in Oxford city than you might expect. (A few respondents were from outside the county or even the UK; we spotted responses from the Netherlands, France and the USA.)

Supporters living in Kidlington argued that the stadium would be good for their village.

“Kidlington has nothing to do and no incentive for people to stay or travel there. This would be a huge boost to the local economy.”

“I have 2 daughters who play for Kidlington Youth FC and it's incredibly frustrating the number of games that are cancelled because the facilities are in such a poor state and have been neglected for far too long.”

“We certainly wouldn't be trapped in our village as there is more than one way in and out. It will create jobs for local people. Bring it on – we can give them a very warm welcome.”

What objectors say

The most prominent theme in objections, by a long chalk, was the traffic impact.

“This is going to make Kidlington a nightmare to get into, and out of, on match days.”

“It will make travelling to and from the City Centre to Kidlington impossible.”

“The talk that 80/90% of fans will arrive by public transport seems optimistic at best and complete nonsense at worst.”

“It is inevitable that match-goers will bring their cars, especially if they realise they can park for free in the many residential roads within easy walking distance of the Triangle site.”

“Diverting traffic along Frieze Way for a minimum of 30 minutes will lead to huge tailbacks. If people cannot access Kidlington on most Saturday afternoons, they will not come to the village to do their shopping or to take part in leisure activities.”

Environmental concerns were also frequent. Some focused on the impact of building a new stadium:

“It is nothing short of climate vandalism to literally throw away all the tons of concrete used to build the Kassam stadium and just pour hundreds more tons somewhere else.”

Others highlighted biodiversity at the Triangle site and the need to protect the Oxford Green Belt:

“The site is rich in biodiversity including, but not confined to, great crested newt, badgers, and bats. The monitoring equipment installed at the site to detect these bats was removed very shortly after it was installed; there have effectively been no bat surveys conducted.”

The separation of Oxford from Kidlington, which prides itself on being a village rather than a suburb, was a totemic issue for several respondents.

“It will interfere with the wildlife and the last part of the green belt we have before we are swallowed up by Oxford.”

“The proposed piece of land, right next door to the A34, is at present full of trees, a green belt, which is what the residents of Kidlington want between us and Oxford, not a huge great football stadium”

Many objectors quoted an Oxford Mail report which claimed that Firoz Kassam, landlord of the eponymous stadium, would be willing for the club to stay. (The report was ambiguously worded and Mr Kassam’s negotiating style is well documented.)

Compared to the supporters, the objectors are much more geographically concentrated – almost exclusively in Kidlington and immediate surroundings, with a few in Bicester.

What happens next?

OUFC’s lease on the Kassam Stadium expires in summer 2026. Working backwards from this date, the club’s original timeline expected construction to start this July. That is clearly now not going to be achieved. We have annotated OUFC’s original timeline:

- July 2023: Public engagement to be undertaken by Oxfordshire County Council. (On schedule - took place in July 2023.)

- September 2023: Oxfordshire County Council cabinet meeting at which a decision will be taken about the use of the Triangle site. (On schedule – took place on 19 September 2023.)

- October 2023: If approval is given by the council for the Triangle, Oxford United Football Club to submit a planning application to Cherwell District Council. (Running late – took place in February 2024, with the application “validated” by Cherwell in March.)

- March 2024: Outcome of planning application by Cherwell District Council. (Running late – expected in July/August 2024 at the earliest, possibly as late as October.)

- July 2024: Subject to planning approval, Oxford United Football Club to commence works on site. (Can only take place once the application is decided and any planning conditions imposed are agreed, which itself can take several months.)

- July 2026: Stadium works are complete, and the stadium is operational.

Delays in submitting the application mean that the project is already running behind schedule. Work on the ground is unlikely to get underway before autumn 2024, and could feasibly be delayed until early 2025 – making the timings very tight for the football season starting in August 2026.

Local politicians are treading carefully around the issue. The two front-runners for the Bicester & Woodstock constituency, Rupert Harrison (Conservative) and Calum Miller (LibDem) do not have any reference to the stadium on their campaign websites. Councillors have to be careful not to “pre-judge” an application by saying anything that would impair their neutrality when assessing it.

The traffic issue

So far, traffic studies are the sticking point. (Warning: this bit gets technical.) As part of its application, OUFC submitted a worked-through traffic simulation (or model) assessing the impact of the development on junctions near the site. This was carried out with a piece of software called LinSig.

However, Oxfordshire County Council – the highway authority – says that this isn’t detailed enough. They have asked for simulations to be carried out with an alternative software package, Vissim, which more accurately models the interaction between junctions and people’s willingness to consider an alternate route. For example, how will queues at the Oxford Parkway traffic lights impact on Kidlington or Cutteslowe roundabouts?

They have been joined in this demand by National Highways, the Government quango that runs the A34. They say:

To inform our view of the potential impact from proposals to the safe and efficient operation of the [A34], it is essential that traffic modelling is undertaken. The applicant has yet to undertake this traffic modelling, however we are currently working with the applicant to scope out the applicant’s required highway modelling exercise.

The results of this simulation are unlikely to be known before June. Recognising this, National Highways have asked Cherwell District Council not to consider the application before 26 June “to enable for the applicant to supply required information and for us to review it”.

Modelling the impact on traffic will be a complex task – especially given Oxford’s trial traffic filters, set to come into operation this autumn. Will these result in more traffic on the A34 and ring road, or encourage Oxford supporters to travel to the stadium by bus rather than car?

Will it happen?

Oxford United’s supporters are clearly enthusiastic about the stadium proposal. It’s common for project proposers to “mobilise the troops” in support, but the outpouring of support in consultation responses is far beyond that.

Particularly remarkable is the cluster of support in Kidlington itself. Though opposition in the village has been vocal and often eloquent, our heatmap analysis shows that Kidlington villagers are as likely to write in support of the stadium as to oppose it.

But as we noted at the start, consultations are not referendums. The 400 voices of support could become 4000, but if traffic issues can’t be resolved to the satisfaction of National Highways, the stadium is unlikely to get permission. Oxford United’s future could rest on one little-known computer simulation.