Housing Week: The Green Belt

It’s remarkable how Oxford has barely grown in 50 years.

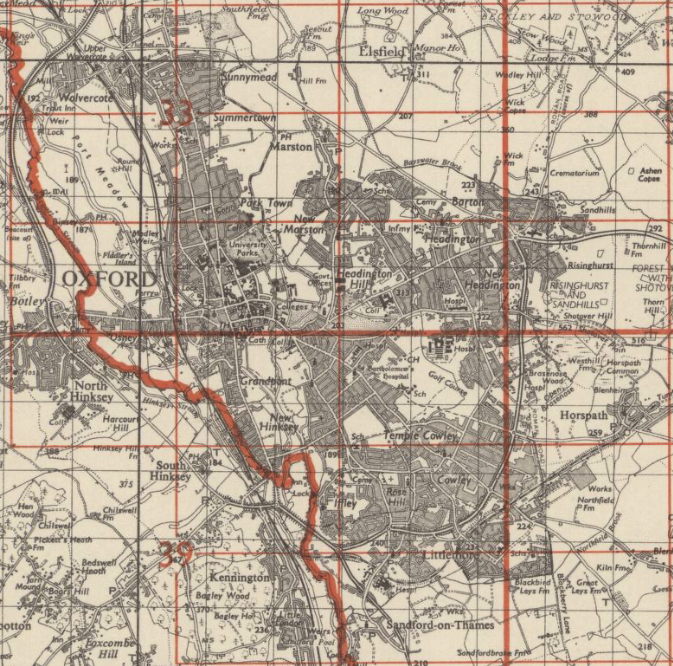

Here’s the city limits in 1968:

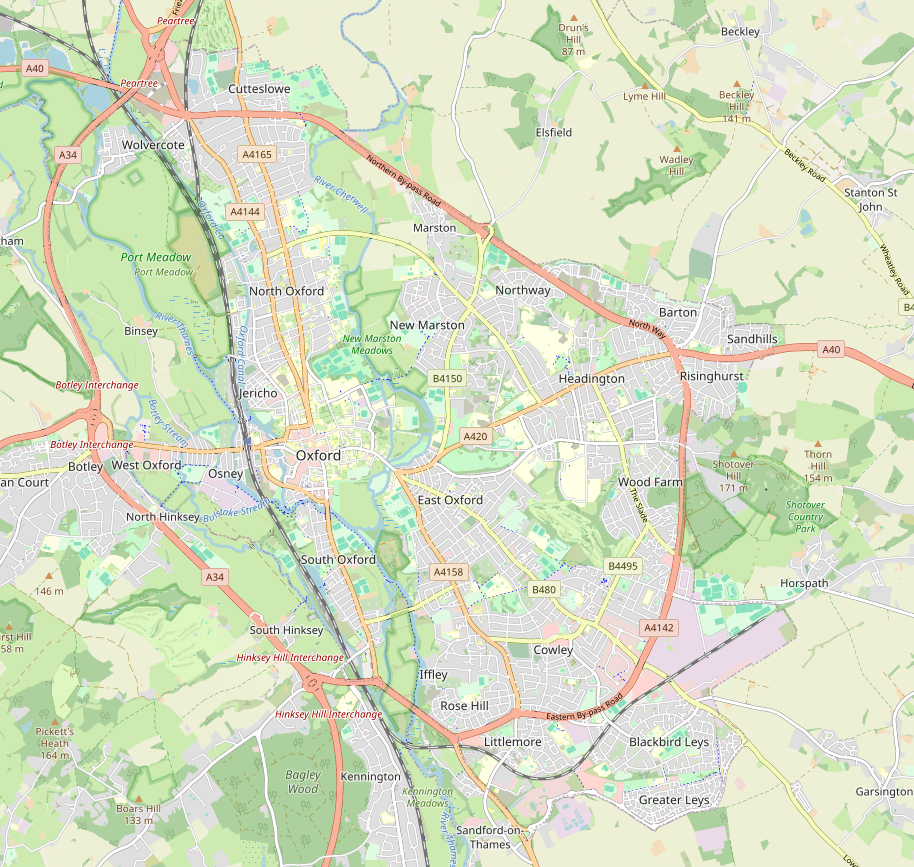

And today:

You can while away a happy half-hour playing ‘Spot the Difference’. Here’s a few starters: Greater Leys (mid-1980s). Barton Park (2019 onwards). A little infill around Sandhills and Wood Farm. These aside, the city remains the same size.

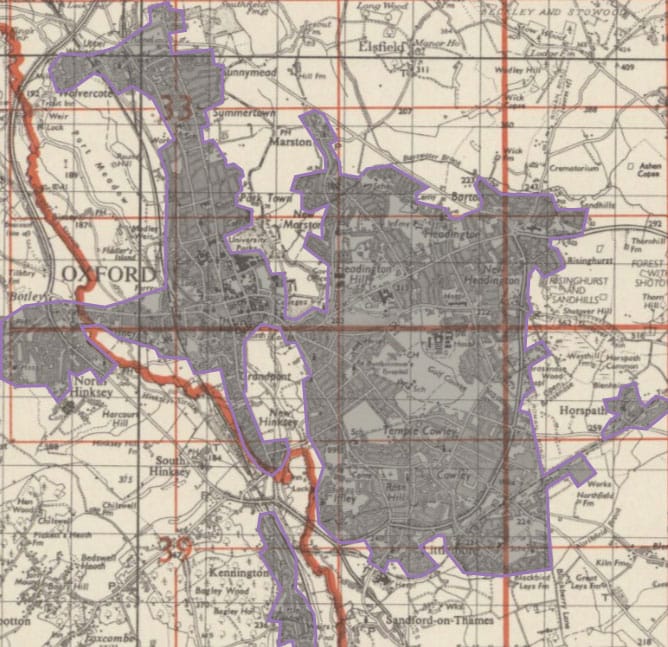

Go back to the 1940s, though, and the picture is very different:

New Marston, Blackbird Leys, Northway, Cowley Marsh – these and more were yet to be built out.

The immediate post-war period was a time of housing development across Britain. Oxford had escaped the worst WWII bombing, so the immediate pressure for rebuilding was less. But Morris/BMC’s pre-eminent role in the new car age encouraged thousands of new houses in south and east Oxford.

Plant Oxford may not be the dominant employer it once was. Still, as we have explored this week, Oxford’s housing demand is greater than ever. What changed after the 1960s? One factor above all: the Green Belt.

The Oxford Green Belt

London had Britain’s first Green Belt, coming into force either side of 1950. Oxford’s was first proposed in 1958, but didn’t take effect until 1975 – around the time the city stopped expanding.

Green Belts are not solely for nature conservation. Their official purposes are to stop low-density sprawl of the sort that tends to encircle dense cities; to prevent settlements merging, so that Eynsham remains Eynsham and isn’t subsumed into Oxford in the way that (say) Headington was; to preserve historic towns, to safeguard the countryside, and to encourage derelict inner-city sites to be reused instead. Unofficially, they also serve to share out development with other cities and towns, and to give city dwellers easy access to the countryside.

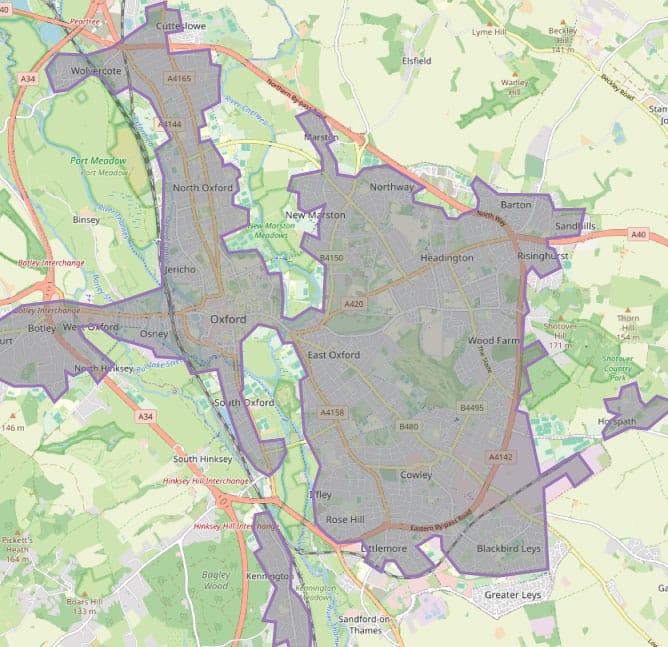

Has Oxford’s Green Belt succeeded on all counts? We’ll consider that later in the article. But it has certainly succeeded in preventing sprawl and settlements merging. Let’s take a look at those two maps again, but with the outline of the 1968 city superimposed on today’s Oxford.

Oxford in 1968 and today, with the 1968 city outline on both maps. (OS/OpenStreetMap.)

Those city areas on the right-hand map outside the purple outline have been built since 1968. In other words, the built-up area of Oxford has hardly grown at all since the Green Belt was introduced.

CPRE, originally the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, is the biggest champion of the Green Belt. It worries about the future, but proudly reels off the Oxford Green Belt’s achievements:

- “The Green Belt provides the ‘countryside next door’ to the city and surrounding villages which is easily accessible for all kinds of recreation…”

- “The vegetation in the open countryside surrounding Oxford provides a carbon sink…”

- “The Green Belt is the city’s ‘green lung’ offering a large area of open countryside and clean air for all local people to enjoy…”

- “Farming and food production is an important priority…”

- “The Green Belt supports wildlife and biodiversity…”

- “The Green Belt provides important resilience to the risk of flooding…”

These concerns are as important today as they were 60 years ago. In an age where we spend hours every day staring at a screen, we yearn for the countryside more than ever. You can hardly move in Blackwells without tripping over a display of the ‘New Nature Writing’ – wild swimming, mindful walking, thoughtful expositions of nature creeping back into the edgelands.

But this bounty is not shared equally between all Oxfordshire’s residents. It’s easy to “get back to nature” if you have copious leisure time – but for many, the countryside is something seen resentfully through a windscreen on the daily commute. Some of us would like to spend less enforced time in the countryside.

The Salt Cross Problem

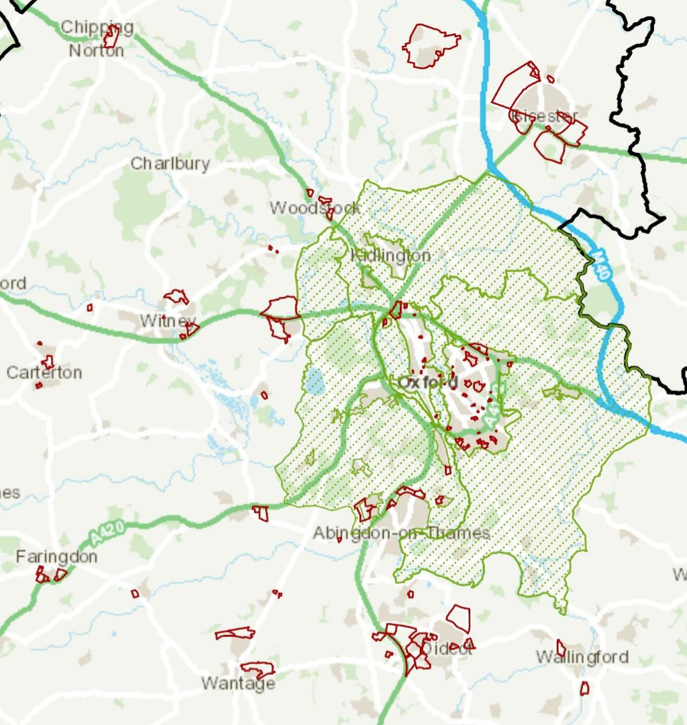

2,200 homes are to be built in the new ‘Garden Village’ of Salt Cross, on the northern edge of Eynsham. Another 1,000 will be built at West Eynsham. You can see them on this development map, two red-outlined areas abutting the western edge of the Green Belt, on the A40 towards Witney.

The Clarion loves little Eynsham, but we are under no illusions that 7,700 more people will decide to move to the village just for the best off-licence in Oxfordshire. The Salt Cross website is blunt about its purpose:

The garden village is being brought forward to help Oxford City Council, which does not have enough housing land, to meet its identified needs. Each of the Oxfordshire local authorities are assisting Oxford and the garden village is West Oxfordshire’s main contribution, together with some further planned housing to the west of Eynsham… The location of the site means it is well placed in relation to key transport links and Oxford City.

In other words, Salt Cross is Oxford overspill, sited as close to Oxford as the Green Belt will allow. There will be some new employment (a small “science and technology park”), but most residents will work in Greater Oxford.

Salt Cross is 7 miles from Carfax. The A40 is among the most congested roads in Oxfordshire, and though a widening scheme is lumbering towards construction, few expect it to be much more than a £180m sticking plaster. Eynsham’s railway was closed in 1965. The much-desired cycleway on the Eynsham–Botley road remains unbuilt: the A40 does have one, but a 14-mile round trip by bike is a big ask. Inevitably, Salt Cross will add more traffic to overcrowded roads.

The Green Belt and sustainable commuting are uneasy bedfellows. It is hard to identify a site of any size within cycling distance from Oxford without encroaching on the Green Belt. Rail is no easier: Culham is in the Green Belt, the rail-served Cotswold villages have their own AONB protection. Unless Oxford’s commuters discover a new love for interurban buses, does the Green Belt risk pushing Oxfordshire’s countryside roads further towards one big traffic jam?

Access to the countryside

CPRE says another purpose of the Green Belt is as “a large area of open countryside and clean air for all local people to enjoy”.

The benefits of clean air and active recreation go without saying. Recent years have added a third string to the bow: mental health. Mind, the mental health charity, extols the virtues of “spending time in green space”. A literature review concluded that “while green space may be important for mental wellbeing, having it nearby doesn’t necessarily mean people will engage with it”.

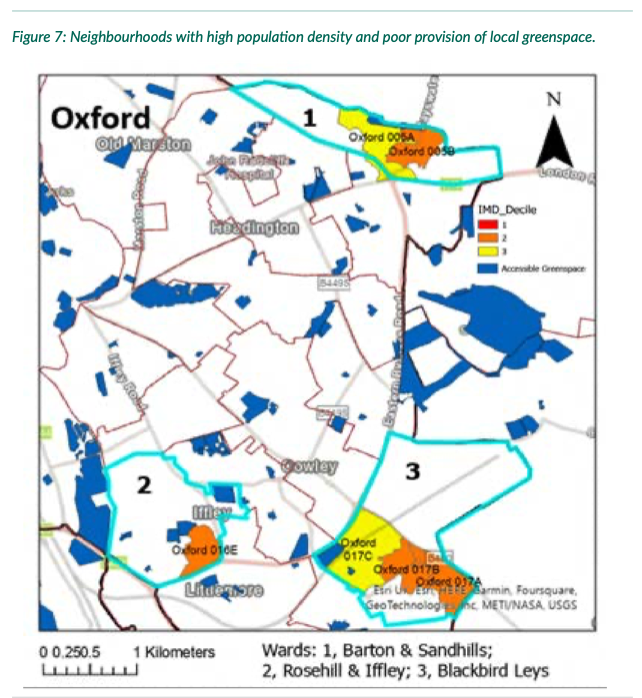

The University of Oxford’s Leverhulme Centre for Nature Recovery looked into this, focusing on Oxford in particular. Its conclusions were alarming. Many of Oxford’s less affluent neighbourhoods are on the edge of the city – the Leys, Barton, Sandhills and Risinghurst. In theory, the Green Belt should ensure their residents have the best access to greenspace.

The reality is anything but. Dr Martha Crockett, author of the report, concluded:

Twelve neighbourhoods have high population density and low provision of accessible greenspace, six of which are in the 30% most deprived neighbourhoods in England, all in Oxford. […] Some of these neighbourhoods occur in clusters, particularly in Blackbird Leys ward where there are three neighbourhoods of concern, two of which are in the 20% most deprived neighbourhoods in England.

In other words, the Green Belt is not currently providing accessible greenspace – with all its health advantages – for the people of Rose Hill, Barton or Blackbird Leys.

The Green Belt does not guarantee footpaths, cycle trails, nature walks or open spaces. Inaccessible farmland is no less Green Belt than a country park. For every Shotover, there are acres upon acres of featureless arable with just the occasional pylon. For every Port Meadow, there is a private estate behind walls and ‘Keep Out’ signs. Indeed, Dr Crockett found that Oxfordshire has no public country parks that meet the “sub-regional” standard (>500 hectares) for accessible greenspace.

The grey belt

The new Labour government wasted no time in unveiling its reforms to the planning system. In July, it set out a long list of changes it wants to make to the National Planning Policy Framework, aka the planning rules for the whole country. (The consultation ends on 24 September.)

The most eyecatching is a new phrase: the “grey belt”. This, put simply, means the bits of the Green Belt that aren’t very green, or in legalese, “Green Belt land which makes a limited contribution to the Green Belt’s purposes” – the five purposes we recounted above. The reforms single out four particular targets:

i. Land containing substantial built development or which is fully enclosed by built form

ii. Land which makes no or very little contribution to preventing neighbouring towns from merging into one another

iii. Land which is dominated by urban land uses, including physical developments

iv. Land which contributes little to preserving the setting and special character of historic towns

Port Meadow would be safe. Otmoor too, by virtue of being a Site of Special Scientific Interest. But the land around Culham? Yarnton? Radley? It’s easy to see how a planning inspector might conclude from these four tests that they qualify as “grey belt”, fair game for new housing. CPRE is worried:

We think the government's definition of 'grey belt' could lead to the degradation of Green Belt land, when we know there's enough brownfield for 1.2m homes. That's why we'll be challenging it.

— CPRE The countryside charity (@CPRE) August 7, 2024

In the meantime, here's why the Green Belt is so important 👇 https://t.co/SmlqjWyl84

In fairness, the traffic is not just one way. Labour’s planning review changes do also include promises to strengthen public access to the countryside.

We are clear that release of ‘grey belt’ land must benefit communities and nature. We know that accessible green space is an integral part of making quality places so the golden rules will include delivering access to good quality green spaces and nature […] We expect local planning authorities to specify clear policies on green space requirements in plans.

This could solve the failings identified in Dr Crockett’s report – that for all their proximity to the Green Belt, Blackbird Leys and Barton residents have little access to green space. But is an optimistic “we expect” enough? Relying on Local Plans to improve access to the countryside is unlikely to have the legal or emotional force of the Green Belt. As West Oxfordshire is currently finding, Local Plan protections are surprisingly fragile.

Team Green or Team Grey?

If you are trying to buy a house in Oxford right now, your reaction to these proposed changes is almost certainly “bring it on”. Seeing houses being built 15 miles along the A40 in Carterton, or a £332m road proposed so that more Oxford commuters can live near Didcot, you might well ask why not simply build on the edge of Oxford instead.

Or maybe you walked your dogs last weekend on Port Meadow, or took a hike across Otmoor, or ambled up the Oxford Canal towpath, or strolled along the Thames downstream of Sandford. The environs of Oxford are special. It’s understandable that people are so passionate about protecting them. Maybe you are one of those people.

If there’s one theme recurring through the Clarion’s Housing Week, it’s this: “no easy answers”. The need to build; the need to prevent sprawl. The two cannot be reconciled.

But perhaps the stark conclusions of Martha Crockett’s report into Oxfordshire greenspace could offer a tentative way forward. Could Oxford pioneer a better Green Belt? One that doesn’t cleave exactly to the boundaries first charted in 1958, but that gives access and health benefits far beyond those on offer today? One that recognises, yes, there is poor-quality Green Belt – and that a solution might include more building, but also opening up more accessible, equitable greenspace.

Did you like this article? We are the Oxford Clarion, an independent news outlet for Oxfordshire. We try and shine a light on the important and the interesting – ideally both – that's often missed by other news outlets. Each Friday, we send out a round up of Oxfordshire’s news, to your inbox, for free. This week is Housing Week and we're also sending you a long read every day. Hit the subscribe button if that sounds like your bag. See you in your inbox?