Oxford University’s Chancellor election: the runners and riders

Just when you thought 2024’s election season was over…

Much like Popes, the Chancellor of the University of Oxford has traditionally had a job until he (and until now, it has always been a he) dies or chooses to retire. Harold Macmillan did it for 27 years, Roy Jenkins for 16. Chris Patten has been in post since 2003. He is now stepping down, at the age of 80.

Unlike Popes, though, the election process is simple, transparent, and involves neither white smoke being sent up from the roof of the Sheldonian nor the phrase “habemus Cancellarium”. The electorate of 250,000 comprises all alumni plus the 5,000 members of Congregation (university staff). For the first time, voting will take place online rather than in person – opening it up to the many alumni who live beyond Oxford. Anyone could nominate themselves as a candidate, the requirement for 50 signatures having been dropped. From this year, Chancellors will serve a 10-year term, so the next election is due in 2034.

The Chancellor is not responsible for day-to-day running of the University. That falls to the Vice-Chancellor, currently neuroscientist Irene Tracey. Rather, the Chancellor is the University’s face to the world, representing it at events, endorsing its fundraising work, and dressing up for a succession of ceremonies both meaningful and arcane.

It’s a prestigious job, and one that attracts national politicians looking for the final act of their career. But the move to online voting, which in effect broadens the franchise, makes this year’s election particularly unpredictable. For over 250 years, Oxford Chancellors have been politicians, all white, all male. Could the University elect a woman for the first time? Will the world’s largest collection of experts decide that “people in this city have had enough of politicians”?

We have summed up the frontrunners in the 38-strong race and taken a look at some of the more unusual candidates. Each applicant was invited to submit a statement to the University, and you can read them in full on its website.

Favourites

Elish Angiolini, William Hague, Peter Mandelson, Jan Royall (official Government portraits)

Elish Angiolini is the Principal of St Hugh’s College. Her background is as a lawyer in Scotland, each appointment more impressive than the last: Solicitor General, then Lord Advocate, then Lord Clerk Register. She led the inquiry into the murder of Sarah Everard. Though she is an alumnus of the University of Strathclyde, she says she has come to love Oxford:

Although I am a late arrival compared with many, I quickly came to view it not only with respect but with affection, and I feel it has warmly embraced me in turn. The appointment comes at a crucial moment in the University’s ongoing story, and calls for a profound understanding of how Oxford’s distinctive history can be reconciled with the changing imperatives of the modern world without sacrificing our unique institutional qualities.

William Hague led the Conservative Party from 1997 to 2001, going on to serve as Foreign Secretary under David Cameron. Having addressed the Tory conference as a comprehensive-educated 16-year old, he read PPE (Philosophy, Politics & Economics) at Magdalen, chaired the Oxford University Conservative Association – being accused of “blatant ballot box stuffing” along the way – and became President of the Oxford Union. His statement recalls this time and seeks to frame it as a “freedom of speech” matter:

Oxford should be a place of open debate – as it was for me in the Union – based on learning from the arguments of others. Violence and prejudice should be countered through the rigour of reason, not the comfort blanket of cancellation. Oxford minds should be ready for the great debating chamber of the world, not the echo chambers of the like-minded.

Peter Mandelson also read PPE, this time at St Catherine’s. He is often described as the original ‘spin doctor’ in British politics, serving under Neil Kinnock and then in cabinet for Tony Blair and Gordon Brown – punctuated by resignations over improper conduct. Blair famously said “My project will be complete when the Labour Party learns to love Peter Mandelson.” Like Hague’s, his statement emphasises freedom of speech, and goes on to address the university sector’s financial woes:

I believe that higher education is an essential public investment and I am against the disproportionate shifting of costs onto individual students. I believe this view is shared by the new UK government including the Prime Minister and I will use my longstanding political links to advocate for this approach. But at the same time, as times are tight, the University will also have to raise more money from our worldwide alumni and from philanthropists.

Jan Royall, Principal of Somerville College and a Labour peer, also sharpened her political teeth working for Neil Kinnock. She was Leader of the House of Lords from 2008 to 2010, and worked on two inquiries into anti-semitism in the Labour Party – one in Oxford University’s own Labour Club, the second in the wider party. She has chaired two ‘town’ thinktanks, the Oxfordshire Inclusive Economy Partnership and the Oxford Strategic Partnership. At Somerville she promoted unconscious bias training, and her Chancellor address emphasises tolerance rather than bare-knuckle debate:

At Somerville, I have relished the opportunity to lead a college where students, academics, and support staff flourish in an atmosphere of respect. The unique, but fragile, tutorial system is special, a model of dialectical teaching which fosters the free and enlightened discourse crucial to our liberal, democratic society. We have made huge strides at Somerville in widening participation, welcoming and supporting students wherever they come from.

Received wisdom is that Oxford votes the “other way” to the incumbent Government, electing the SDP’s Roy Jenkins as Chancellor in 1987, and the Conservative Chris Patten in 2003. We think this tends to be overstated – Jenkins and Patten were essentially moderate centrists rather than fiery opposition figures – and so we wouldn’t write off Peter Mandelson or Jan Royall on this basis.

William Hague’s time as Foreign Secretary gives him a world presence that a university dependent on donations sorely needs, though Peter Mandelson is no jet-setting novice having been European Commissioner for Trade. Mandelson’s decision to row in on the perceived side of “freedom of speech” perhaps blunts one of Hague’s USPs.

All told, though, we wonder whether the careful, considered approach of Elish Angiolini might be the most appealing to an international electorate wary of wading into culture wars. The Clarion isn’t betting on this race, but if we were, we wouldn’t bet against Angiolini.

Outside chance

Alastair Bruce (photo: Cpl Nick Johns), Margaret Casely-Hayford (own website), Dominic Grieve (Government portrait), Simon Kay (NHS), Harry Stratton (own website), David Willetts (Government portrait).

Alastair Bruce (full name: Major-General Alastair Andrew Bernard Reiby Bruce of Crionaich OBE VR DL) was “the first openly gay General in the British Army” – which, he says, gives him an understanding of diversity and inclusion issues. He ran the Army’s media unit, and continues a TV career both as a Royal commentator and (much to the excitement of our friends at the Oxford Mail) historical adviser to Downton Abbey. As Governor of Edinburgh Castle, he says, “I know how to pull the levers of awareness, interest and joy, in order to draw in the distant, disconnected and disinterested.” (Ideal skills for a lecturer, you’d think?)

Margaret Casely-Hayford is a lawyer whose CV is studded with spells on the boards of John Lewis, the Co-op, ActionAid, Great Ormond Street, Shakespeare’s Globe and NHS England. Her family, of Ghanaian origin, were once named “the most influential black family in the UK”. She is an honorary fellow of Somerville. Her statement promises to cherish Oxford’s “soft power” and nurture its alumni network: “I want to inspire others from diverse backgrounds both socially and economically to apply, attend and graduate from our great university.”

Dominic Grieve was Attorney General under David Cameron but, as a rebel Europhile, had the Conservative whip removed by Boris Johnson. In Oxford he is perhaps best known for chairing the review into the governance of Christ Church after the Martyn Percy dispute, a fraught situation which most observers believe he handled adroitly. “At 68 and still scuba diving and mountain walking,” he pledges, “I am confident that I have the energy to do this.” His take on freedom of speech is perhaps more nuanced than some: “I am committed to the principles underpinning human rights, equality and the right to freedom of expression under law and with civility, essential to a place of learning.” Unusually, he has set up a campaign website.

Simon Kay is an Oxford graduate who went on to be a reconstructive plastic surgeon in Leeds, carrying out the UK’s first hand transplant; he has lectured and written numerous papers on the topic. He concedes “I am not a widely known public figure” but turns that around to say “…and so have none of the baggage of a celebrity or politician”. With Oxford recently being rated the best Clinical & Health university in the world, there will be some affection for the only medic in the race.

Harry Stratton is running to be “Oxford’s first progressive, campaigning Chancellor… using the biggest bully pulpit in the University to put pressure on the administration, and the government, to treat our staff and students fairly”. A union activist from East London, his candidacy promises a shop-stewardish ‘look what I can do for you’ rather than a globe-trotting ambassador for the University. He promises a £15/hour minimum wage, an end to exams-only finals, and opposition to increasing tuition fees; he claims “I haven’t invaded any Middle Eastern countries or deported any of the Windrush generation”. His campaign website exhorts voters to “put the Tories last!”.

David Willetts is another of said Tories. He was Minister for Universities under David Cameron, closely associating him with the rise in tuition fees from £3,225 to £9,000. He studied PPE at Christ Church but it wasn’t until becoming an MP that he gained the nickname ‘Two Brains’. His statement touts his globetrotting connections in China, America, and mainland Europe, but says Oxford is falling behind financially. “Research excellence is another great Oxford attribute but other leading universities have access to much greater resources: the Chancellor should be able to help narrow that gap.”

The “I love my university” candidates

So from the 10 candidates who could win, to the 28 who can’t. But their statements are still worth perusing if only for the love for Oxford University that shines through so many of them.

George Callaghan is an Oxford tour guide: “I am prouder of being an Oxford graduate than anything else.” Emma Dandy graduated from Balliol in PPE in 1994, before tuition fees, and believes finances are holding today’s young people back from the opportunities she had. Maxim Parr-Reid, who appeared on University Challenge for Trinity, says “I have always been captivated by the ceremony of Oxford” and praises the “excellent tutors”.

Angie Moxham recounts how her time at St John’s in the 1980s made her “one of the most successful female operators in my industry of the last 30 years” (as she tells the memorably titled nowankybollocks.com). Lyn Michelle Heiming studied at Wadham, also in the 1980s, and says “I answered my father, over 30 years ago, when he asked me what my dream job would be, with ‘The Chancellor of the University of Oxford’.”

Kadira Pethiyagoda recalls: “Growing up as a Sri Lankan migrant shaped by Tolkien, Carroll etc., Oxford was always a place of wonder, redemption and kindness.” Xingang Wang arrived at Christ Church after a childhood in “a modest village in the north of China”, and wants the university to be “not just the greatest university on the planet but a force for good in an ever-changing world”. Ammora Ayham says his time at Oxford gave him “a profound appreciation for the University’s commitment to fostering intellectual curiosity”.

The “I hate my university” candidates

Matthew Firth describes himself as “an ordained Anglican clergyman” though he currently practices in the fringe Free Church of England, which was set up in opposition to the 19th century Oxford Movement. (Maybe a bit late to fight that particular battle?) Claiming that “great academic institutions are being ruined by woke ideology”, he goes on to say that “should the university or any college or department walk the way of wokery”, he would threaten “a strong public rebuke”.

Also-rans

Candidates from the world over – but particularly the Indian subcontinent – have nominated themselves for the role. Some are junior academics, some local functionaries, some entrepreneurs. And although we don’t think that the founder of Neutra Fruit Delight Pvt Ltd is going to win the Chancellorship this time round, it’s heart-warming to see the regard in which Oxford is held globally. You can read the full list on the University website. Here are a few highlights:

“I am a simple student, a poor immigrant, and a passionate soul. Who cares about the big names? They’re all old anyway, they will probably pop off soon and I’ll be back here anyway so let’s skip ahead and elect me Chancellor of Oxford for a safe and secure university .” (Francisc Vladovici Poplauschi)

“I am so much in to physical activities like hiking trails, gym, swimming, gym and I even teach Zumba. Zumba is something, that not only keeps your body active but your mond as well. This will again help me manage responsibilities of a Chancellor.” (Tanya Tajik)

“I may not have experience in politics in public office, but I have personally seen the ways that talking to people in ways that open their eyes to unseen possibilities in a way that moves their needle just the tiniest bit and can bring even the most unexpected person into your cohort.” (Mei Rose Connor. We love the joke on her website.)

“Be smiled.” (Kashif Bilal)

Non-runners

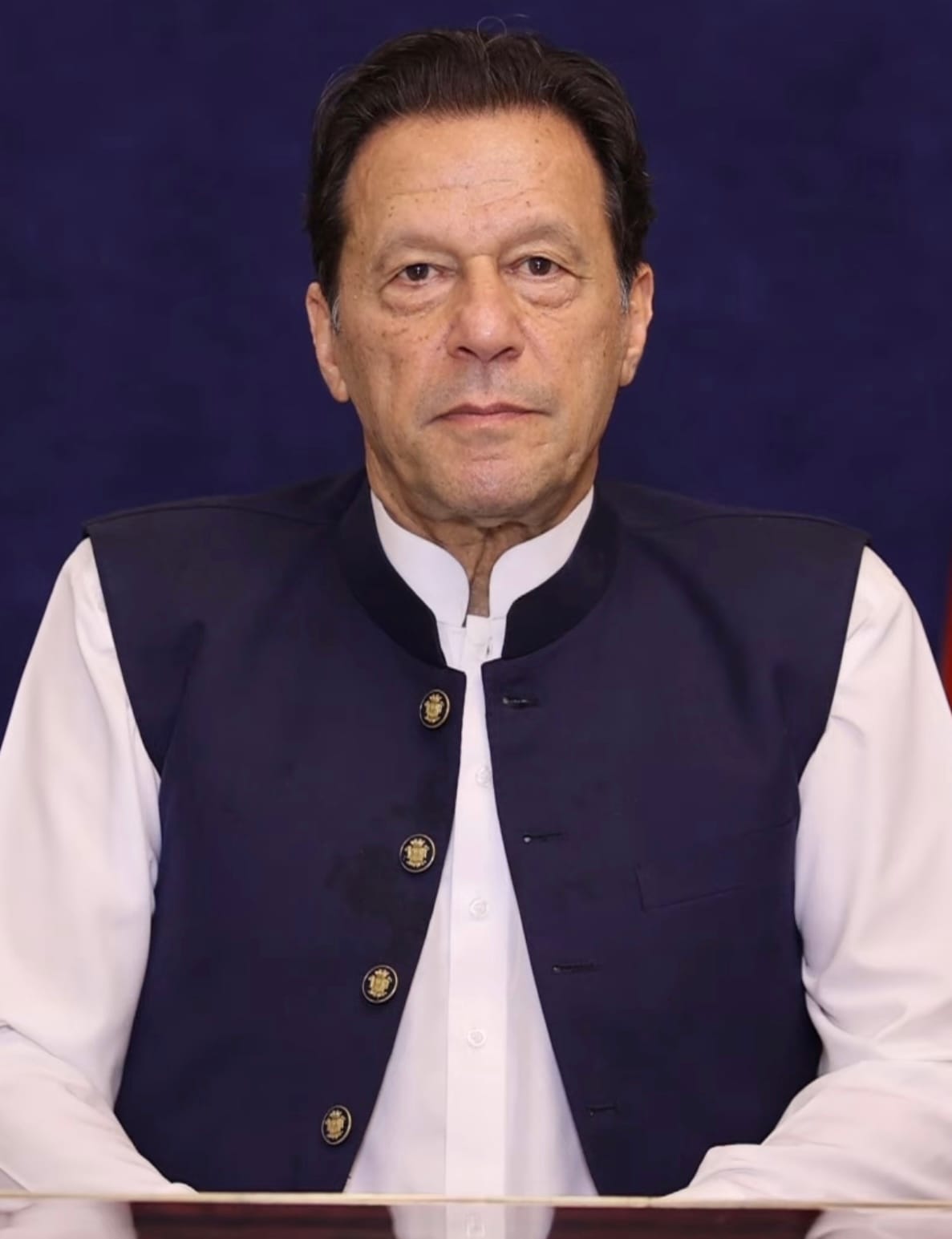

Imran Khan, Theresa May, Rory Stewart (Wikimedia Commons)

Imran Khan – Keble graduate, international cricketer, and Prime Minister of Pakistan from 2018 to 2022 – was said in July to be running. He is currently imprisoned on disputed corruption charges. His non-appearance on the list has provoked speculation that the university has “blocked” him, but no announcement has been made to that effect: a statement confirmed merely that “a small number of applicants” (unnamed) did not make the list due to the “specific exclusion criteria set out in the University regulations”. Those regulations are fairly terse, but do refer to HM Revenue & Customs’ own requirement that a charity trustee must be a “fit and proper person”. This, of course, is open to interpretation.

Other rumoured candidates absented themselves early on, including former MP Rory Stewart who tweeted “There are much better candidates than me”. Former Prime Minister Theresa May also withdrew from the race, sadly without using the slogan “Oxit means Oxit”.

How the election works

The election will be held in two rounds. The first round takes place online in the week beginning 28 October. Each voter will be asked to rank their preferred candidates in order, with votes redistributed using a form of the Alternative Vote system.

Once this has winnowed the list down to a shortlist of five, a second round of voting will be held (in the week beginning 18 November). Again, voters will rank their preferred candidates, with the lowest-scoring candidates eliminated and their votes redistributed until a single candidate has 50% of the vote. The result will be announced in the week beginning 25 November.

What message will the electors want to send? Will they be seeking an internationalist candidate to counter Brexit’s effect on research and Britain’s withdrawal from the Erasmus scheme? Could disenchantment with politics lead to rejecting the perceived Conservative and Labour candidates? Will online voting encourage overt campaigning rather than a battle fought in the letters pages of the Times? Or will it simply be business as usual and the election of another male politician?

It is 800 years since the first Chancellor took office. Robert Grosseteste (literally ‘Big Head’) is said to have taken up the post in 1224, though sources are inexact. He is said to be “the real founder of the tradition of scientific thought in medieval Oxford”. Maybe, after 800 years, the University at the heart of British science will move on from electing Roberts, Ralphs, Richards and Roys and choose an Elish or a Jan.