Oxford’s commuter future

Could Oxford learn from Copenhagen and Cambridge? We ask if rail commuting could be an answer to the city’s housing woes.

In 1947, Copenhagen’s Urban Planning Institute set out a “finger plan” for development of the city. To avoid uncontrolled sprawl, the finger plan proposed that new houses would be built in towns or suburbs along five railway lines (or ‘fingers’), stretching out from the city centre.

Every resident would be in easy cycling or walking distance of a fast train service to central Copenhagen. Meanwhile, green ‘wedges’ between fingers retained public access to the countryside, woodland, lakes and hiking trails. It’s been a remarkable success, so much so that a sixth finger was later added with its own brand-new railway.

No British town has formally adopted a finger plan. But Cambridge has uncanny echoes of one. Rail commuting into Cambridge has ballooned in recent years. Over 2 million rail journeys are now made into Cambridge every year from nearby commuter towns, over twice Oxford’s figure. Ely alone supplies half a million. Small towns like Meldreth, Audley End, Whittlesford and Shelford each top 60,000 journeys to Cambridge.

By contrast, the Banbury–Oxford total is less than half that of Ely–Cambridge – and Oxford’s numbers fall off fast. In fact, just three stations have annual rail passenger flows to Oxford of between 50,000 and 150,000: Birmingham New Street, London Marylebone, and Hanborough. Only one of those is a commuter village. Cambridge has 17 in this bracket, including places like Waterbeach (92,000), Newmarket (87,000), Meldreth (67,000), Audley End (67,000), Shelford (61,000) and Whittlesford (54,000).

(Data visualisation courtesy of John Courouble.)

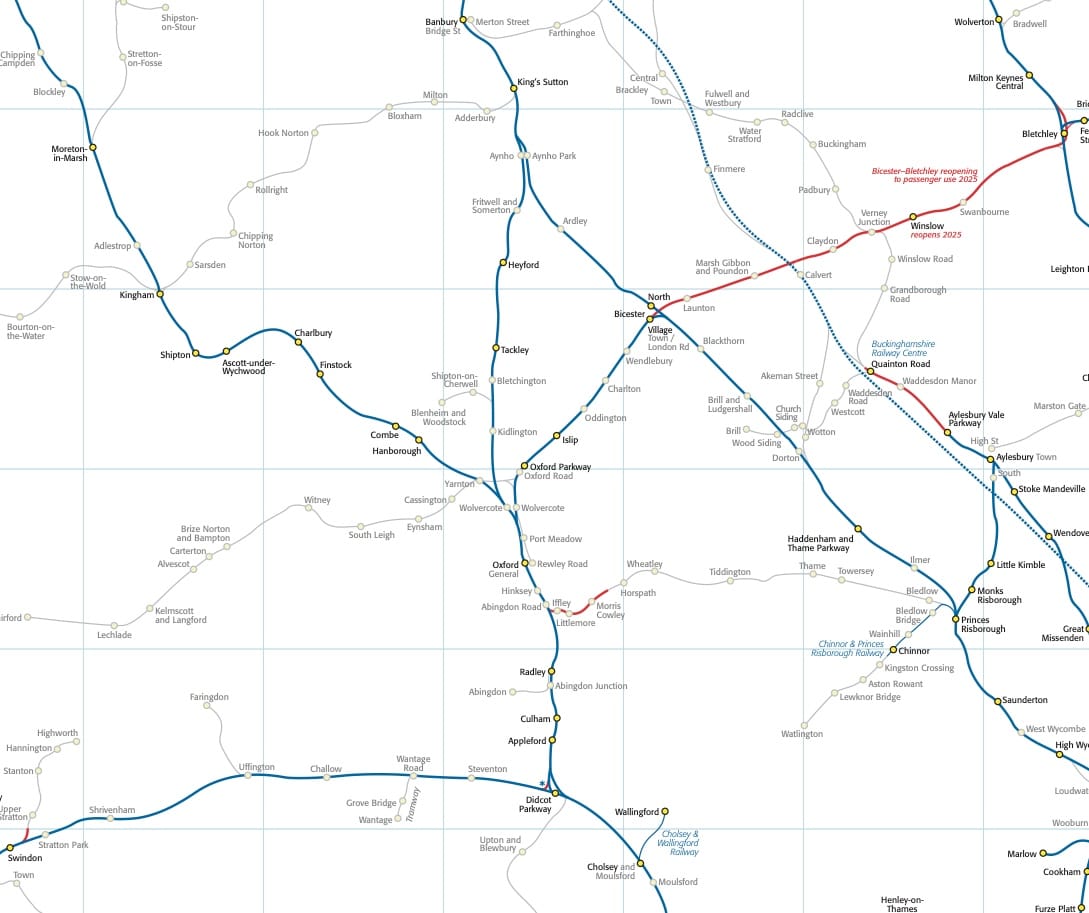

Four railway lines radiate from Oxford, the same number as Cambridge. Oxfordshire has no shortage of rail-served villages. Regular rail travellers will know the announcements: “Tackley, Heyford, King’s Sutton and Banbury”; “Hanborough, Charlbury, Kingham, Moreton-in-Marsh”; “Radley, Culham, Appleford and Didcot Parkway”.

Could Oxford tackle its housing crunch and beat congestion by learning from Copenhagen and, dare we say it, Cambridge? Is a rail commuter future the answer that’s been staring us in the face? Let’s look at the practicalities.

Oxfordshire’s railway landscape

First, a quick geographical primer. We mentioned Oxford’s four railway lines. They are the Banbury line (calling at Heyford, Banbury, King’s Sutton, Banbury, and on to Birmingham); the Bicester line (calling at Islip, Bicester Village, and on to London Marylebone or, soon, Milton Keynes); the Cotswold line (calling at Hanborough, Charlbury, Moreton-in-Marsh, and on to Worcester); and the Didcot line (calling at Radley, Culham, Appleford, Didcot, Cholsey, Goring & Streatley, and on to Reading and Paddington). Here’s a map.

Two further railways were closed in the Beeching era. The Witney line is largely ploughed up though there’s active interest in rebuilding it. The Cowley branch line survives as far as Mini Plant Oxford for freight trains; it once ran beyond to Wheatley and Thame. There were even branch lines to Abingdon, Woodstock, Chipping Norton and Faringdon.

Trains or no trains, the pace of building around Oxfordshire is remarkable. A drive or cycle around Banbury, Bicester, or non-rail-served towns like Witney or Carterton will show hundreds of new houses going up. For most of these new residents, the daily commute begins with stepping into a car. Oxford’s roads are already full; other county roads are heading that way. How do we build new houses where cars are not the first choice for travel?

Densifying railway towns

Let’s start with the easiest win: redeveloping the areas around existing railway stations with denser housing.

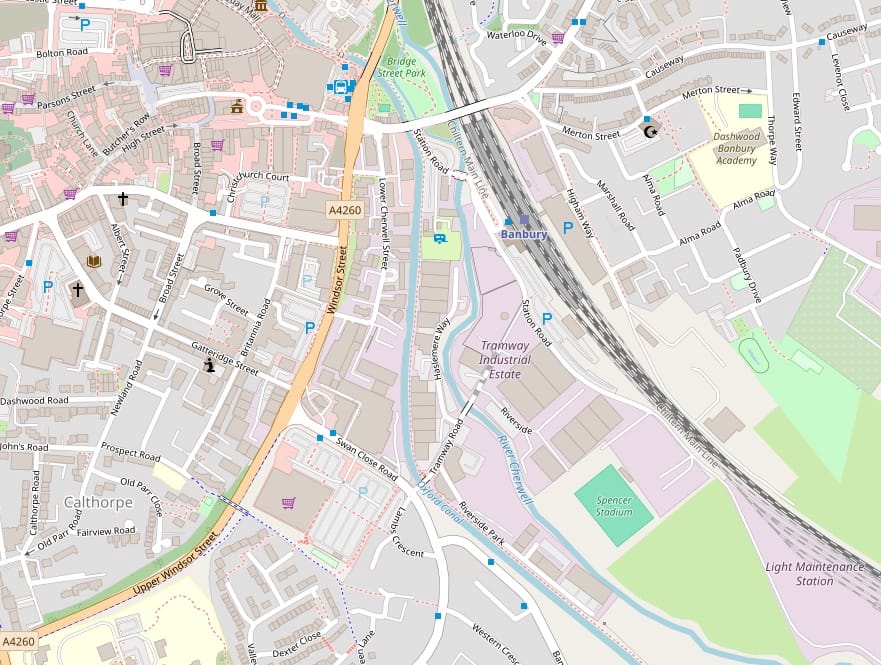

Banbury station is the best example. The Tramway Industrial Estate, immediately south of the station, is low-density light commercial use – ‘sheds’ that derive little benefit from being in the town centre. Cherwell District Council has tentatively identified this area for 700 homes (originally 1200) under the Canalside banner, but with no discernible progress since 2018.

Near Didcot Parkway, Vauxhall Barracks is due to close in 2034. Again, the district council has earmarked it for housing. South Oxfordshire’s development brief envisaged medium-density housing with 1.5 car parking spaces per dwelling, providing just 300 homes. But there is an opportunity to be aggressively ‘rail-first’, reducing parking to free up room for more houses. At a smaller site directly opposite the station, Didcot Gateway, plans for new council offices have been put on hold, opening up the possibility of more housing.

One promising sign is a small new development on Broadway, an easy walk from Didcot Parkway. Here, nine apartments and a community space are replacing a derelict former youth centre, to a tightly packed car-free plan.

Oxfordshire towns were historically dense. Particularly in the north and west of the county, the predominant town centre form is the two to three-storey terrace. Late 20th century detached suburbia has been a departure from a tradition lasting centuries. Dense housing doesn’t have to mean urban high-rises (though there’s a place for that); simply reviving the Oxfordshire market town model could mean less land take, not more.

Dense, terraced development in central Banbury. 1. General Views, CC-BY 2.0; 2,3. Elliott Brown, CC-BY 2.0.

New towns

Faced with a housing crisis, creaking infrastructure, and a hostile planning system, every recent Government has fallen back on “new towns”, “garden villages”, “eco-towns” or similar. The taskforce set up by the current Government duly reported that new towns should “have effective public transport within the town itself as well as links to wider transport networks” – and nine times out of ten, the latter means railways. By summer 2025 (yes, that’s now), the taskforce promises to submit “a list of places new towns could potentially be located”.

Oxfordshire has a head start on rail-connected new towns. We wrote about Culham last year, where 3,500 new homes could be built next to the existing station and the Culham Science Centre. But right now, Culham New Town is not a construction site, not even a live planning application, just an aspiration in a Local Plan.

At Heyford Park, 6,000 homes could be built on a former airfield between Banbury and Bicester. Heyford already has a station on the line to Oxford, 2.5 miles from Heyford Park. There’s also talk of a second station at Ardley, two miles east, which would provide residents with direct trains to London Marylebone. But existing Heyford Park residents are critical of the developers’ failure to provide adequate infrastructure. If thousands of new residents are to take the train rather than clogging the A34, they’ll need a traffic-free cycleway and shuttle bus service to these stations at the minimum.

The 2,200-home Salt Cross garden village is popularly described as an outgrowth of Eynsham, but it’s only two miles from Hanborough station, which has regular trains to Oxford and Paddington. Again, the infrastructure of a safe cycleway and shuttle bus to Hanborough will be necessary to tempt commuters away from the A40.

Gallons of (electronic) ink have been spilled over concept drawings for new towns in the Oxford–Cambridge Corridor. We won’t even attempt to summarise them, let alone weigh up their competing claims. But the notion of a new town between Bicester and Milton Keynes keeps coming up. Sometimes this is an expansion of Winslow; sometimes an all-new town at Calvert, six miles nearer Bicester.

Rural expansion

Building homes in rural areas can be fraught. Kingham and Charlbury are in the Cotswold National Landscape, which adds extra planning worries. The Cherwell floodplain at Tackley and Kings Sutton, and the steep sides of the Evenlode valley at Charlbury, pose physical challenges.

Still, there’s undoubtedly scope for more housing near Oxfordshire’s existing country stations. A case could be made for building at Kingham (National Landscape notwithstanding), Appleford, Hanborough, Haddenham, and Islip, at the least. Cholsey should be ideal for development, but since electrification was halted at Didcot, the village no longer has through trains to Oxford.

Thame will only be 2 miles from Haddenham station if/when the much-vaunted Greenway is built. Adderbury doesn’t have a station, but building a new cycle path would put it within 1.3 miles of Kings Sutton station. Hanborough is 2.2 miles from Woodstock. Safe cycleways can greatly increase the reach of a rural station.

Even rural areas don’t have infinite land. Recent developments around Radley have been built to a cookie-cutter suburban pattern with double driveways galore, heavy on the shrubbery and with surplus “community green spaces” when most residents would prefer to spend time in the existing meadows or river paths. This is arguably a waste of valuable rail-adjacent land, artificially limiting the number of residents in walking distance from Radley station.

Further afield

The commuter of 2026 can reach Oxford on a fast, direct train from more places than in 2014. New on the arrivals board are Haddenham, Princes Risborough, High Wycombe on the Chiltern line, and Winslow, Bletchley, Milton Keynes on East West Rail. Winslow – a placename which we would bet is entirely unfamiliar to 99% of Oxford residents – will only be 30 minutes’ train ride from Oxford station. There are buses that take that long to get in from the city outskirts.

If GWR succeeds in turning its trial Saturday Oxford–Bristol service into a week-round regular, you could add Swindon to that list. Swindon is never going to become a dormitory town for Oxford, to the relief of Swindonians and OUFC supporters alike. But we’d expect some inbound commuting, partly a result of property prices, partly among families where only one adult works in Oxford.

More stations

Of all the long-running Oxfordshire stories that the Clarion reports on, the Wantage & Grove station campaign is the no-est of no-brainers. The town/village combination has a population of over 20,000. Grove is literally on the Great Western Main Line. Five trains in each direction already pass it every hour. The alternatives are sub-par A roads.

So why is there no station yet? Partly it’s the sclerotic structure of the modern railway industry. When the original Great Western Railway built a station here in 1846, it could simply buy up the land, build the station, and install some signals.

In the 21st century, progress means that Oxfordshire County Council needs to draw up an outline case sponsored by a local MP, bid to the national Government’s “Restoring Your Railway” fund, receive development funding, commission a more detailed study, bid again with this as evidence, and so on. Then in 2021 the Restoring Your Railway fund is closed to new applicants, and in 2025 withdrawn entirely. The relevant page on gov.uk proudly says “The New Stations Fund has delivered 8 new stations across England and Wales since its inception in 2014.” Eleven years. Eight stations. Er… well done?

Still, OCC and Vale of White Horse have succeeded in commissioning a series of studies, with an early report estimating the cost at £18.2m. This is on the low side for a railway station, where £25m is the going rate. But building the station is only half the battle.

West of Didcot, the Great Western Main Line is mostly two tracks. When a stopping train calls at a minor station, it obstructs the Cardiff express behind. We say “mostly” because there’s a short length of four-track railway around Wantage & Grove where, in theory, the express can overtake – yet it’s not clear whether the extra tracks are long enough. Rail authorities are very nervous right now about adding more trains to the timetable that work on paper, but in practice reduce reliability. Three operators have just been refused access to the West Coast Main Line for exactly that reason.

(But this, of course, is why you commission studies to find the real answers, rather than relying on the opinions of jaded Clarion hacks with deep-seated trauma from being stranded at Didcot Parkway after a failed connection.)

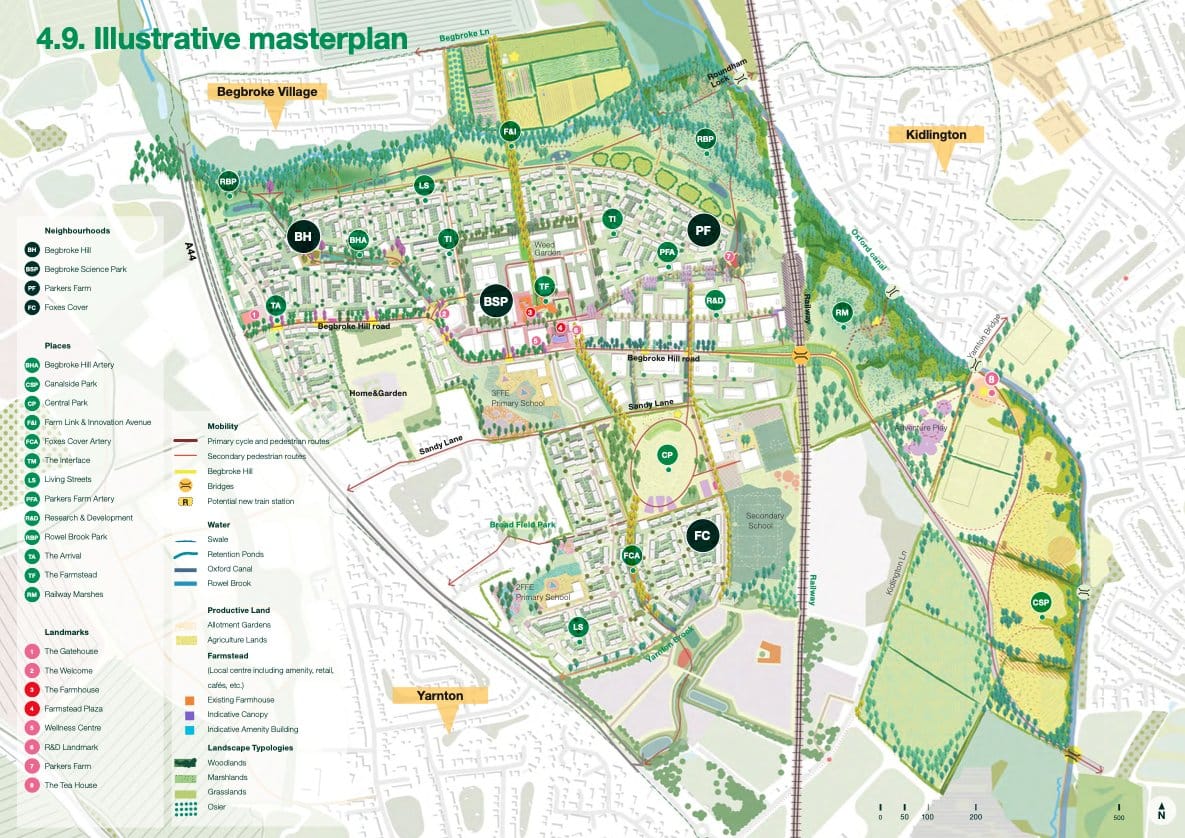

Oxfordshire’s fourth proposed station (after adding the two on the Cowley Branch Line) is at Begbroke, near Kidlington, in connection with the housing and science park development unfolding in the area. This could be served by an more frequent stopping service between Oxford and Banbury. It’s been described as a “halt”, which hints at cost-saving possibilities: in an age when most people buy tickets on their phones, is there really a need for a ticket office building? With houses and labs adjacent, can a car park simply be omitted? Could the cost of a footbridge be shared with providing a public path to Kidlington?

Siting employers by stations

You might be wondering why we’ve barely mentioned the Cowley Branch Line so far.

It’s tempting to assume that the challenge is simply to ship more people to Oxford station every morning, and out again in the evening. But although Oxford is a compact city, not every workplace is in easy reach of the station. Staff at the John Radcliffe, for example, still have three miles (along) and 50m (up) to go. In other words, employees don’t just need to live near stations: employers need to be near stations too.

Oxford is doing well here. The upcoming Oxpens and Osney Mead developments are both a short stroll from the central station. The Oxford North quarter is close to Oxford Parkway, though a direct walking/Brompton route is needed rather than the dogleg via Wolvercote Roundabout and its painfully slow pedestrian crossings. There are railside employers outside Oxford, like the Culham Campus, and visitor destinations, like Oxford United’s proposed new stadium.

Here’s where the Cowley Branch Line comes in. Of course, it will be a boon to residents of Littlemore and Blackbird Leys, as well as new house-building around the former Kassam Stadium site. But perhaps more significant is the inbound traffic, to the hi-tech industries and lab space at the Oxford Science Park, ARC Oxford, and soon, the Ozone. A direct rail link will make train commuting the natural choice for hundreds of employees – a fact not lost on employers who have launched their own Campaign for the Cowley Branch Line.

Other new stations are planned with employment in mind. Begbroke would serve the University’s research campus, while Wantage & Grove would be on the doorstep of Williams F1.

Improving connections across towns

Received wisdom among transport planners is that once a commuter steps into their car, it’s hard to get them out again. Where driving all the way is just too painful, such as journeys to London or increasingly Oxford, then commuters will consider a ‘parkway’ arrangement where they drive to the station. But the biggest modal shift happens when there’s no need to use a car for any part of the journey.

It’s two miles from Bicester’s outermost point to Bicester Village station. Banbury and Didcot are similar. Walking four miles every day adds an hour or more to the commute time. By bike, the same journey is just 10 minutes each way. If those 10 minutes are on dangerous and congested roads, though, few will cycle.

Encouragingly, Bicester is moving in the right direction. Oxfordshire County Council has recently unveiled plans for safe, segregated cycleways along London Road and Middleton Stoney Road, key routes from housing estates towards the town’s two stations. Elsewhere, progress is slower: we’ve seen no sign of carving cycle space out of Banbury’s wide highways, for example.

This isn’t an issue restricted to the start of the journey. The final leg of your journey, from station to office, is typically by foot, bike or bus. If you work in central Oxford, for example, you’re likely to walk along Hythe Bridge Street – a dispiriting experience where pedestrians are crammed onto a narrow pavement, while single-occupancy cars enjoy two traffic lanes. The bus station is 600 yards distant. We’ve written extensively, of course, on the inadequacy of Oxford’s cycle lanes.

Infrastructure is the biggest challenge, but not the only one. Train operators do their damnedest to discourage passengers from taking bikes on trains. If your office is beyond easy walking distance from the station, bike and scooter hire schemes are a real boon. (Especially e-bikes: the 2.5 mile path from Didcot Parkway to Milton Park is honestly tedious, and electric assist makes the journey much more tolerable.)

In other words, attracting commuters to rail doesn’t stop at Oxford station. The whole end-to-end journey needs to be safe, easy and inviting…

Metro-level service

…and frequent. Train planners speak of “generalised journey time”, which factors in frequency as well as point-to-point time to estimate the time to reach your destination. Put simply, a train that takes 15 minutes to reach Oxford is less compelling if that train only runs every two hours.

Banbury residents may be allowed a rueful chuckle here. CrossCountry Trains, regularly rated as Britain’s worst train operator, cut its Banbury–Oxford frequency from half-hourly to hourly during Covid. A handful of these trains have since crept back into the timetable, but passengers are still regularly left on the platform in the evening peak.

Cambridge’s rail boom is built on frequent services. Ely residents have four services to Cambridge every hour, some of them eight carriages long. From Royston, there are between three and six each hour. GWR does run eight-carriage commuter trains out of Paddington, but since the 2016 Government cancelled electrification from Didcot to Oxford, many Oxford commuter services are restricted to rattling two-coach diesels.

Even Oxfordshire’s best-served lines have only a half-hourly service at peak times (more or less), sometimes dropping down to hourly off-peak. It’s some way off the ‘Oxfordshire Metro’ concept of frequent, full-length trains.

Lucky Bicester will go up to four trains per hour when East-West Rail opens, but both Banbury and Didcot sorely need more, longer trains. An extra Chiltern service from Oxford to Birmingham Moor Street via Banbury has long been mooted, and could perhaps be viable now Chiltern has acquired more trains.

Are we getting it right?

Many developments planned in Oxfordshire right now are embarrassingly unaware of their railway potential.

For example, take the Blenheim Estate’s application for 500 new homes on the edge of Woodstock, among the biggest developments to come before a planning committee this year. The application’s Travel Plan says “The regional and national rail network can be accessed at Oxford railway station.” Only by the brave: at rush hour, Oxford station is typically one hour from Woodstock by bus or car.

Hanborough railway station, on the other hand, is just two miles from Woodstock – ten minutes by car or bike. For commuters to London or Reading, it’s the natural choice. But the Travel Plan appears completely ignorant of its existence. That’s a problem, because the cycle route from Woodstock to Hanborough station desperately needs upgrading – an upgrade that the developers could fund. There is a bus from Woodstock to Hanborough, the S7; but only now, two years after it started running, is its timetable being adjusted to tie in with train times.

Train operators themselves are often strangely keen to dissuade customers. CrossCountry’s Oxford–Banbury service, using short, badly designed trains, is a cause célèbre. Culham and Appleford saw their service reduced after GWR was told by Government to trim its budget. Today’s Oxford–Marylebone service is some 20 minutes slower than at launch.

Going beyond

The A40 from Witney to Oxford is perhaps Oxfordshire’s most congested transport corridor. An active local campaign to rebuild the railway (a Beeching-era casualty) has seen some support from Oxfordshire County Council, who commissioned a feasibility study. It concluded, yes, it would be feasible: but it would also cost at least £700m.

You could draw up a long shopping list of rail schemes for Oxfordshire. A tram-train for Oxford, perhaps extending the Cowley Branch Line to Wheatley? (A Stadler Citylink tram can get up a 10% incline, so the closed Horspath Tunnel need not be an obstacle.) Electrification from Didcot to Oxford; redoubling the single line from Wolvercote to Hanborough and Charlbury; the list goes on. None would be cheap. Scotland and Wales have embraced reopening branch lines, while trams and metro systems are now commonplace north of Watford Gap. but right now, Oxfordshire would be foolish to pin its plans on distant dreams.

The impact on Oxford station

Oxford station is barely able to cope with its current number of passengers. If you’ve ever stood on platform 3 in times of disruption, or queued for the ticket gates after an express from London disgorges its human cargo, we won’t need to convince you of that.

The City Council has commissioned masterplan work for the main station building (the east side), while Network Rail is planning a new entrance/exit for the northbound platform (the west side). Leaving aside whether two different bodies redesigning one side of the station each is a smart idea, neither is moving forward at any pace. The City Council says “some preliminary options are currently being developed and tested”, while Network Rail has postponed station works until the Botley Road bridge is complete:

“We are focusing on reopening of Botley Road as the priority, as requested by the Department for Transport. Design and planning works will continue on […] the new platform 5 and Western entrance but most of the construction work for those elements will be rephased to start following the completion of Botley Road.”

The can can’t be kicked down the Botley Road much longer. Crowding conditions will worsen when East West Rail begins later this year. Every single one of the projects we’ve set out will add more passengers to the mêlée. The Botley Road bridge works expand line capacity, but not station capacity. Rebuilding the station building and bridge should be comparatively easy: no Victorian inverts lurking underground, no signalling to rewire, just a plain ol’ building.

(And can we put a plea in for somewhere to buy a decent cup of coffee? Come on.)

The next departure

How many new homes does Oxfordshire need?

Oxford City Council says 10,000 within the city boundaries by 2036, with a further 15,000 “as close as possible”. Cherwell District Council is planning 24,500 by 2042. The other districts have similar numbers.

At current rates, only a fraction of those new residents will commute by train. Many will live in towns without rail, or work at offices far from stations, or simply have a job that doesn’t lend itself to rail commuting.

But this scale of building will stress Oxfordshire’s transport infrastructure to breaking point. Rail is not the only solution to move thousands of people across the county, but it is the best solution. Roads like the A34 and A40 are already full, and road widening simply pushes the problem further into Oxford.

By contrast, Oxfordshire’s railways could accommodate many more commuters every day with relatively little investment. Cambridge’s two million annual journeys should be a target Oxford can hit. Some of this can be achieved by rail improvements alone: more frequent services, longer trains, new stations, reopening the Cowley Branch Line.

Oxfordshire County Council is inching towards the realisation that the county’s railways can do more. It is pushing forward plans for Wantage & Grove station and a reopened Witney line. Its ‘OxRail 2040: plan for rail’ strategy goes out to consultation in September. Crucially, as well as railway upgrades, it focuses on “Rail as place-shaper” – the idea that housing can be developed with rail transport aforethought. West Oxfordshire is thinking similarly, saying a reopened Witney line “could transform how we grow as a district”.

As ever, good intentions are hampered by the decisions on housing (city/district councils) being taken in a different office from those on transport (county council, rail authorities). But with unitary councils coming down the track, is the time finally right?

Cambridge is a nice model. Copenhagen is a better one. The Danes’ finger plan shows that the real gains come when we focus housing development around stations. Thousands of new rail-adjacent homes at Banbury Canalside, Culham, and Didcot’s Vauxhall Barracks should be a right-now priority, not a future dream. Residents elsewhere in Banbury and Bicester need safe, direct cycleways and shuttle buses to their stations.

The finger plan worked not because it was a railway plan, but because it was a housing plan. For the county’s thousands of new residents to get to work quickly, with minimal climate impact, and affordably, Oxfordshire needs to build homes near stations, and stations near homes.