Oxford’s hidden food emergency – and the community filling the gaps

“What are your plans for next week?” asks Dave. Maria tells him that it's her birthday.

As a volunteer for Oxford Mutual Aid (OMA), which delivers food to people across the city, Dave calls Maria every week to check on any food needs or preferences and signpost her to wider services where necessary. It’s a throwaway remark from Maria, but he remembers it.

The following week, Maria sends a message to say that her birthday has been the best she’s had in a while. After a surprise delivery of eggs, butter, flour and sugar from Oxford Mutual Aid, she made a cake with her family. And to top it off, they had steak in the package too. “I was amazed,” she says.

From tiny acorns...

Maria is one of thousands of people who receive deliveries across the city. What began as a Facebook group in lockdown for trading supplies, crocheting masks and running errands is now a city-wide movement, and the biggest provider of food to those who need it in Oxford. Operating six days a week from the Richard Benson Hall on Cowley Road, they delivered over 10,000 packages last year. They estimate that they have reached more than one in twenty households across the city since they started.

While similar Covid-19 mutual aid groups have long vanished, OMA has persisted not just as a logistics network but also as an idea: that communities can organise and look after themselves. Its day-to-day work is quietly universal. Deliveries go to retired people living alone, to veterans struggling with rising costs, to families with young children, to shift workers juggling multiple jobs, to asylum seekers and unpaid carers. The principle is simple: anyone can need help at some point and anyone can give it too.

There are two main types of delivery. A bespoke weekly package provides a consistent, reliable supply of food, household items, toiletries and even baby supplies for new and expecting parents. Alongside this, an emergency service offers rapid, by-request delivery. Both the speed of the emergency service and the predictability of the regular delivery matters. Knowing that food will arrive consistently removes a major source of stress. As one person explained: “It really gave me breathing space… I was completely lost at the beginning, and this became a constant good thing in my life.”

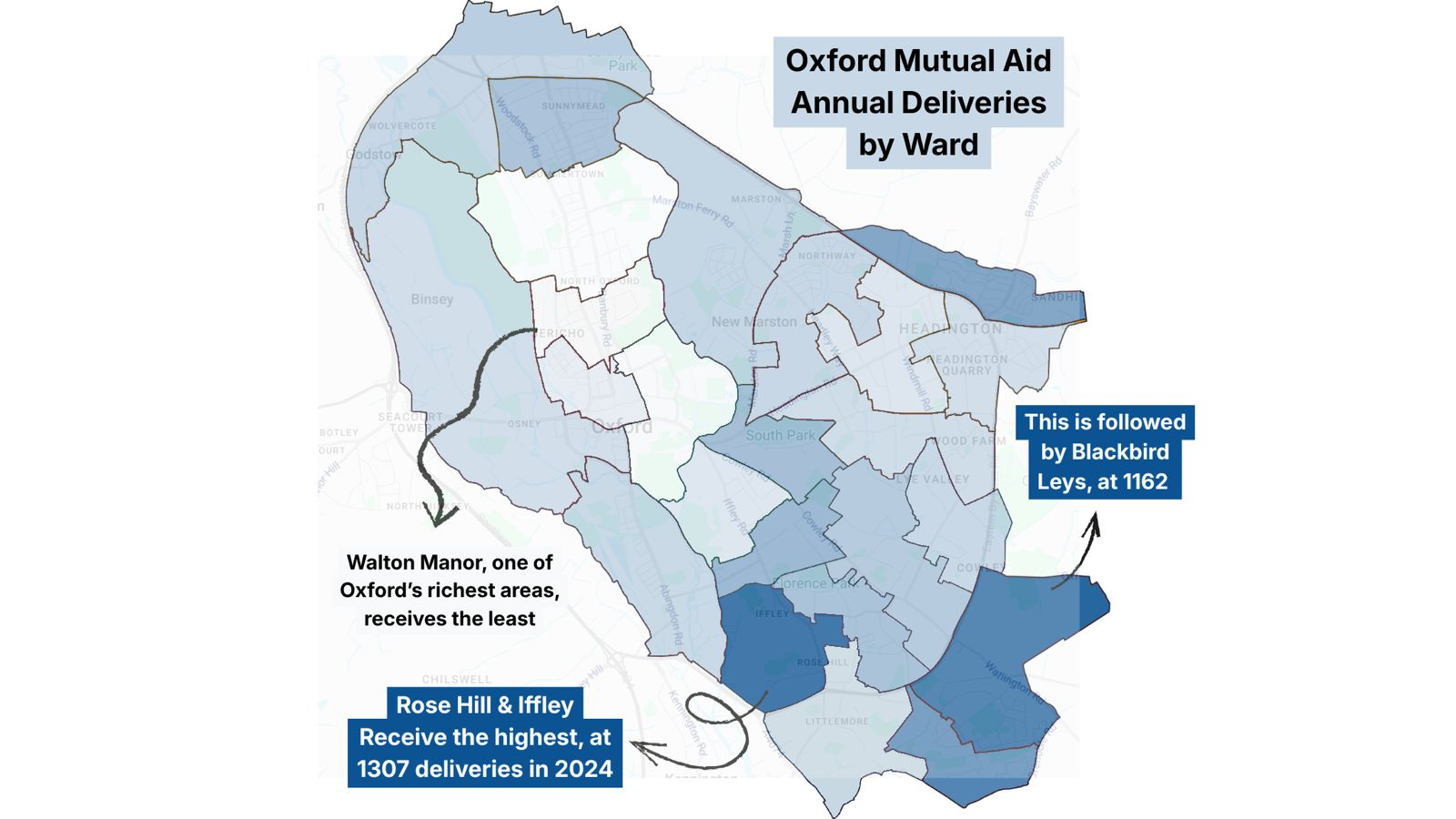

Oxford’s map of inequality

Despite its wealthy reputation, Oxford is one of the least affordable, most unequal cities in the UK. More than one in ten households are estimated to be affected by food poverty according to Oxfordshire's Food Strategy (2022). In Greater Leys, where around a fifth of OMA recipients live, residents live on average eight years less than those in high-income areas. When the cheapest food options are often high in sugar and fat, people on lower incomes can be at greater risk of diet-related diseases such as heart disease and Type 2 diabetes. The deliveries “give me the feeling that I'm looking after my body”, said one recipient.

Sometimes the two Oxfords are side-by-side, and patches in Oxford’s food safety net emerge. “Someone who had been moved into temporary council accommodation in Summertown rang up and asked whether I could refer them to anything in the area,” said Alfie Davis, OMA’s Director of Operations. “Of course there are no food banks there because the majority of the people in that area don’t need them.” It can be the same when people move to villages at the edge of Oxford for council housing or temporary accommodation. Food prices are often higher in these areas too. OMA is the only service of its kind which delivers to every corner of the city.

Businesses to bicycles: Oxford comes together

Meet Tom. He started volunteering at OMA because he “wanted to make a real, tangible difference in [his] local community” and his involvement whilst unemployed helped him “feel like you're part of something bigger”. Trio, packing up a box beside him, volunteers because she “loves the win-win of avoiding wasting surplus from the food retail process, and using it to feed people in food poverty”. Like many, Trio both receives parcels and volunteers in her own right.

“When I was unemployed I couldn't afford to pay for rent, bills and food from my standard universal credit payment. Without my OMA parcel there's no way I would have coped.”

Being able to volunteer to help pack as well helped her “accept that anyone can be both a giver and a receiver in life… we all have the potential to be both”.

Delivery volunteers don’t just drop off the food; they pick it up too. Every month, they rescue more than 20 tonnes of edible produce from supermarkets, shops, and restaurants, preventing it from going to waste. That’s the weight of three elephants.

Donations come from around the city – from local food businesses including Hamblin Bread, Wild Honey, and Taste Tibet, as well as from larger supermarkets and partner organisations. This plays an important role in cutting the city’s food waste and ensures that OMA operates more cheaply than similar organisations. In fact, they have worked out that putting together and delivering a food package costs half of what it costs a national charity, despite the latter’s economies of scale.

While they have so many brilliant volunteers who pick up and drop off food, Alfie tells me that a lack of delivery volunteers is their single biggest barrier to reaching the people that need them.

No questions asked

“Solidarity not charity” is a common slogan in mutual aid groups, emphasising two-way, horizontal support rather than a top-down model. Recipients talk about “food that was free with no expectation. I didn't have to provide any proof that I was applying for Universal Credit”. Anyone can self-refer via OMA’s website, email, or phone line. Applications are not means-tested. This means they often reach people who find themselves in a gap between support services.

“There is a tremendous amount of guilt and shame around needing support and being seen as taking more than you deserve,” Alfie tells me. “I’ve had people sobbing on the phone when requesting a parcel because they feel so ashamed they need support. We all need help at different times in our life, and the work we do here is to try and make that help as accessible and stigma-free as possible.”

OMA operates under the ethos that individuals are themselves the best judge of deciding the help that they need. Alfie notes that means-testing is often an unwise use of resources: “Means-testing programmes often cost much more than they save, all for the sake of excluding a few people.”

Unpaid carers make up 15% of people receiving supplies. Over a third of the people that OMA reach are children under 12; over half are under 18. This hints at an important reality behind the figures: families being stretched thin as inflation rises, and carers quietly doing everything they can to look after others in their household. Disabled people make up over half of package recipients, with the delivery model setting OMA apart from other community food projects that require people to visit a fixed location.

GPs, social workers and community groups point people towards OMA, meaning that they often provide custom deliveries for those in temporary accommodation, catering for their restricted cooking facilities.

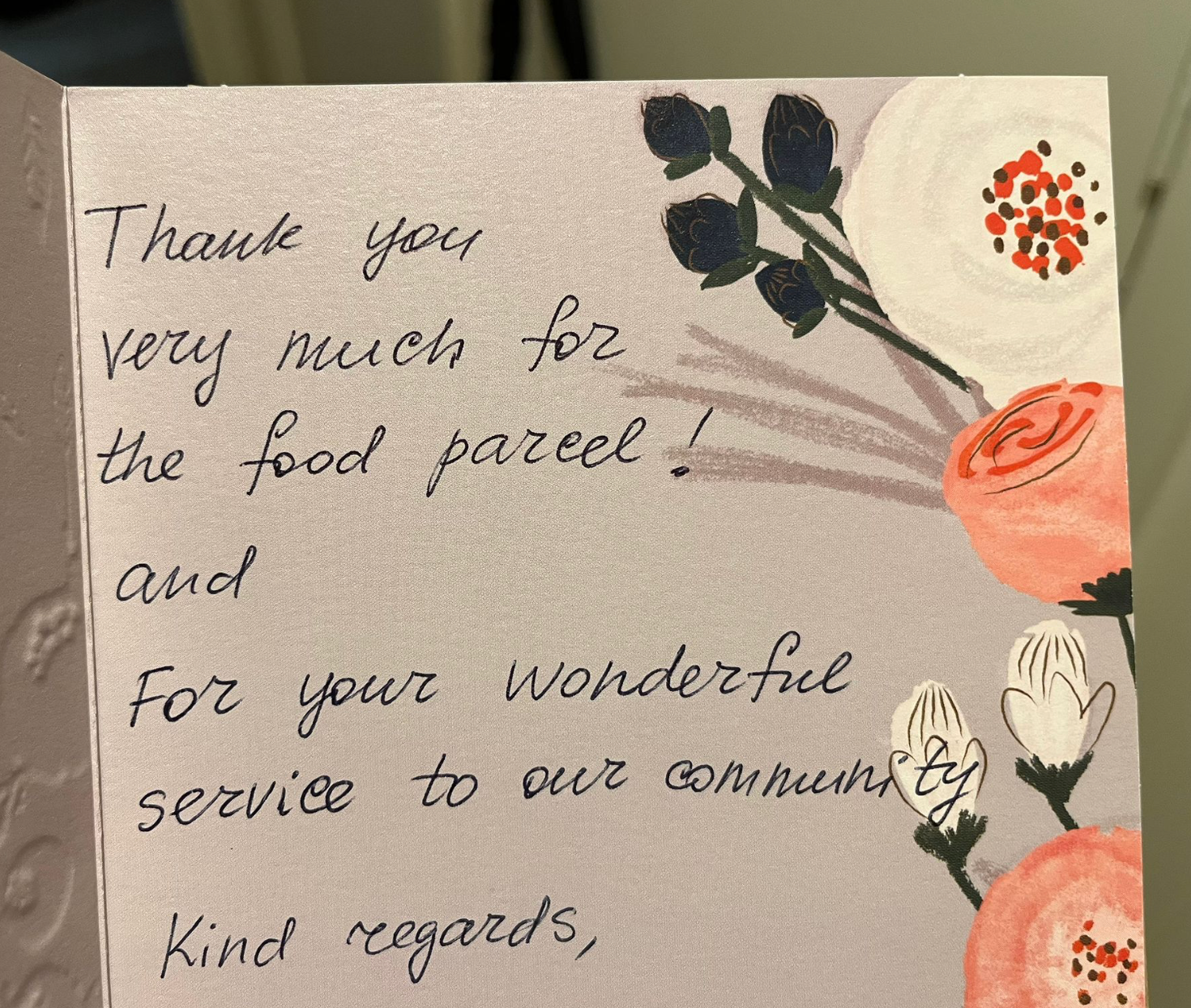

“Thank you” notes from OMA recipients. The text on the right-hand box reads “To a friend. It's not much compared to the sacrifices you make in order to help support people like me, but I hope you like the gift.”

Extra touches

Alfie describes OMA as “acts of care from local people who've sort of put it together and built it up”. But what does this care look like? For some, it is the personalised touches enabled by the regular weekly phone calls.

“It's even little things – like a few months ago … I had a lovely, like, extra big package with tons of nurturing things and a letter to say, you know, we really like hearing about you and the cats, and we thought we'd put together an extra special package for you. And obviously I burst into tears because it was just, yeah, really lovely, nurturing and special things. So it's been wonderful having support from OMA.”

“People in poverty shouldn't have to live off the bare minimum,” Alfie adds. “If we can go out of our way to give someone their favourite brand of snacks, for example, then why shouldn't we?”

Solidarity is not transactional; it is rooted in the understanding that communities are deeply interconnected. Alfie tells me about people who have received deliveries while navigating illness, job loss, or other personal upheaval. The same people have sent messages weeks or months later saying that they’ve found work and would like to give a regular donation of £20 a month. For OMA, this isn’t unusual. It’s what mutual aid looks like in practice: resources flowing in and out of people’s lives as their circumstances change. The strength of a community lies in its willingness to work together as people navigate those shifts.

“I feel quite emotional when I think about it, but OMA has given me, you know… two and a half years of kind, caring support. Back then, I was in a complete mess, you know, just horrendous. It's been a constant in my life that's helped me to really turn things around, which has been, yeah, just really lovely.”

Rising demand

While the cost of living crisis can come in and out of the headlines, OMA has seen a steady rise in demand. In 2025, they received more than double the monthly average of first-time requests for emergency support compared to the previous year. Last week they received almost 100 emergency package requests, numbers not seen since the pandemic.

Everywhere around Oxford, volunteers are coming forward to meet this demand, doing what they can. From packing, collecting surplus and delivering; to social media and fundraising efforts, calling recipients, organising case-management support and assisting with administrative tasks. Much of the work is designed to be done remotely, so low-mobility volunteers and staff can contribute in vital ways.

The alliances across the city are growing too. OMA is part of the OX4 Food Crew, an alliance of seven local food poverty organisations working together. They also partner with The Porch, another wonderful organisation providing food support to people experiencing homelessness. Their growing partnerships with other food organisations, neighbourhood groups, and advocacy networks reflect a shift from crisis response to systemic challenge.

It is a reminder that when people in Oxford work together, they can be there for their neighbours, with both determination and dignity, one delivery at a time.

Oxford Mutual Aid are currently fundraising to try and increase their capacity, following pandemic-level demand in November. If you would like to donate whatever you can, you can do so here. If you would like to volunteer as a parcel packer, driver, biker, caller or other volunteer, you can sign up here.

Thank you to Phil Perry for contributing this article to the Clarion. Names have been changed.