Oxford’s new billionaires

Do you know your Blavatniks from your Bukhmans, your Saïds from your Schwarzmans? We take a look at Oxford University’s 21st century donors.

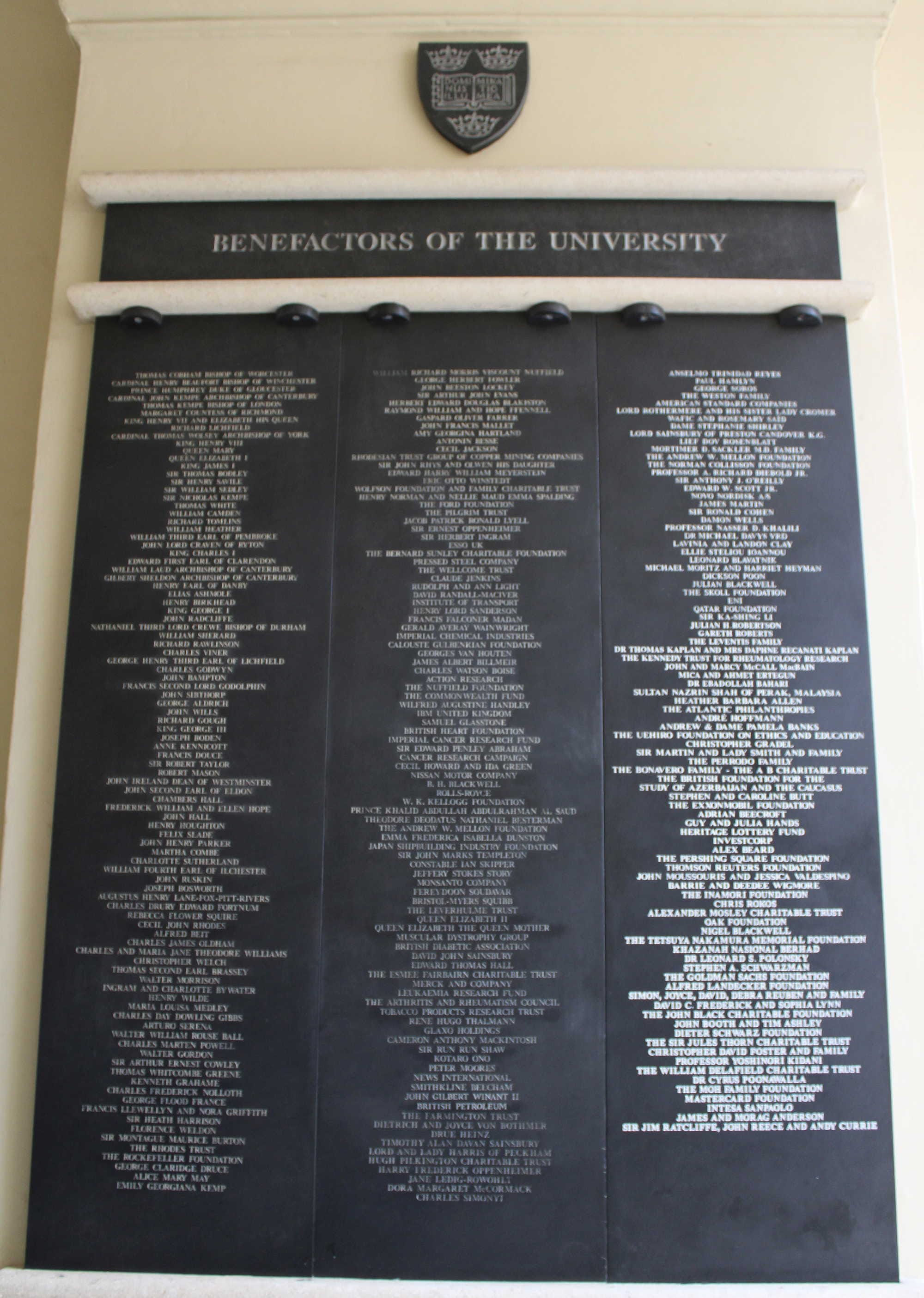

For centuries, Oxford’s university buildings have each been adorned with the name of a benefactor: Radcliffe, Rhodes, Nuffield, Templeton and Green. In Part 1, we started with Cardinal Wolsey and progressed through Rhodes to the 2010s; now we look at the names adorning the city’s latest rash of landmark buildings.

Leonard Blavatnik (Mark Neyman/ Government Press Office of Israel, CC BY-SA 3.0); the Blavatnik School of Government (Martin Cooper, CC BY-SA 2.0).

Sir Leonard Blavatnik

The Blavatnik School of Government was founded in 2010 thanks to a gift of £75m from the Blavatnik Family Foundation. Following in Oxford’s long tradition of educating the world’s leaders, it has a lofty vision: “a world better led, a world better served and a world better governed”. It's early days, but alumni already range from the youngest Member of Parliament in Panama's National Assembly, to an Assistant Governor in the Central Bank of Malaysia – and one Oxfordshire MP, Calum Miller, formerly the BSG’s Chief Operating Officer.

Sir Leonard Blavatnik is a Ukrainian-born British-American businessman and philanthropist, ranked the 75th richest person in the world. Born in Odesa, his family emigrated to the USA in 1978. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Blavatnik used his holding company, Access Industries, to buy up former state assets in Russia – particularly aluminium smelters and oil companies. He divested his last Russian holding, aluminium producer United Co. Rusal International PJSC, in 2022.

In 2015, the Guardian published an article highly critical of Blavatnik's donation to the University. Critics demanded that Oxford “stop selling its reputation to Putin’s associates”. Blavatnik's lawyers responded that “Mr Blavatnik is not an associate of Vladimir Putin, and he is a strong believer in encouraging democracy and freedom throughout the world.” Not everyone is convinced, as he remains sanctioned by Ukraine. (The Blavatnik Foundation says “We condemn the ongoing violence in Ukraine and are actively donating to charitable organizations which help Ukrainians displaced by Russia’s invasion.”)

On a lighter note, the Blavatnik building's most formidable enemy appears to be a playful seagull.

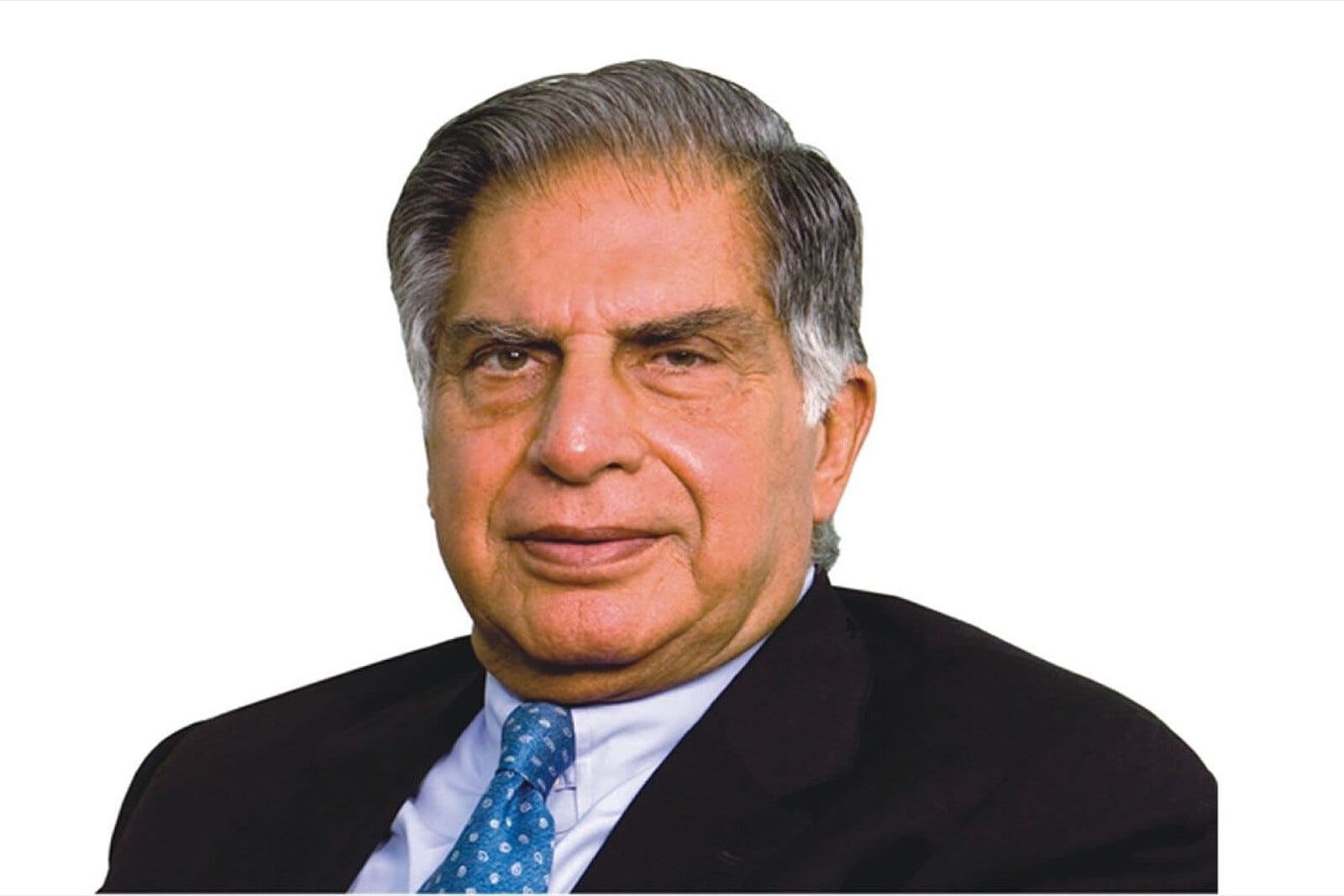

Ratan Tata (Wikimedia commons); an artist's impression of the Ratan Tata building at Somerville College.

Ratan Tata

Indian billionaire Ratan Tata was “a dear friend of Somerville” according to outgoing college principal Baroness Royall. Educated in America, he had no prior connection with Oxford or the university.

Tata Group is an industrial conglomerate known for making cars and steel. It owns Tetley Tea, Jaguar Land Rover, and formerly Corus (the successor to British Steel); it withdrew from Port Talbot in South Wales last September, two weeks before Ratan Tata's death. The Ratan Tata Building in Somerville College will be the first building in the university named after an Indian, and home to the Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development.

Dr Sadok Besrour

In May 2025, the university announced the establishment of the new Dr Sadok Besrour Professorship of Global Primary Care, and a dedicated Besrour Centre for Global Primary Care in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. It will focus on improving access to high-quality, evidence-based primary care worldwide.

Dr Besrour is a Canadian physician whose leadership and philanthropy led to the founding of the original Besrour Centre for Global Family Medicine in Canada in 2014. He has supported the development of family medicine academic programmes (what we call “general practice” or “primary care” in the UK), improved training for generalist physicians, and strengthened teaching capacity in low- and middle-income countries through education, research, and international collaboration.

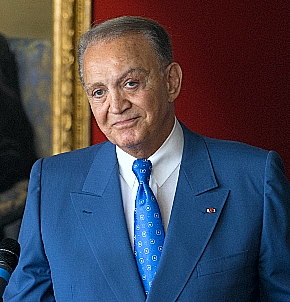

Wafic Saïd; the Saïd Business School (Philip Halling at geograph, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Wafic Saïd

The Saïd Business School is unmissable to anyone arriving to Oxford by train. Its imposing building opposite the station was designed by leading architects Jeremy Dixon and Edward Jones, also responsible for the Royal Opera House in London.

Its doors opened in 2001 thanks to a £23 million benefaction from businessman and philanthropist Wafic Saïd, who by 2014 had donated over £70m to the school. In medieval times it was the site of Rewley Abbey, a 13th-century centre of learning for Cistercian monks. Saïd also established the Saïd Foundation, which supports education, healthcare, and humanitarian relief across Syria, the Middle East, and the UK.

Wafic Saïd started his career as a banker for UBS in Geneva, then became a restaurateur in London before turning to construction in Saudi Arabia. Following the oil boom, his companies played a crucial role in building the airports, desalination plants, housing and hospitals which helped to rapidly develop Saudi Arabia. Saïd helped facilitate the immensely controversial al-Yamamah arms deal between the British and Saudi governments in the 1980s. This was the biggest export deal in British history, generating £43bn in revenue for BAE Systems.

Saïd's role in al-Yamamah has led to him being described as an arms dealer, a term that he rejects:

“The deal brought a huge boost to British industry: you are talking about thousands of jobs. But for some reason, which I cannot understand, the press want to portray this as a shady, mysterious deal... Quite honestly, I thought I was doing this country a favour; I have never even sold a penknife. I was not paid a penny [for advising British Aerospace], but I benefited because the project led to construction in Saudi Arabia that involved my companies.”

Saïd's philanthropic efforts for the university have seen him honoured with the Sheldon Medal, awarded annually to a member of the Chancellor's Court of Benefactors who has “made a strategic difference to the life of the university”. A bust of Saïd by artist Michael Rizzello stands at the entrance to the Saïd Business School, it was one of the last works sculpted by Rizzello before his death in 2004.

This spring, the Saïd Business School is due to open its Global Leadership Centre, a new teaching and residential facility for the School’s prestigious executive education programmes on the site of the former Osney Power Station, thanks to another £15m gift from Saïd.

The Bukhman family

Igor & Dmitri Bukhman founded mobile games developer Playrix in Russia, moving its headquarters to Ireland in 2013. Their sister, Anastasia, runs the Creative restaurant company in London. Igor and Anastasia together run the Bukhman Foundation with a mission to “foster a healthier, more creative, and more inclusive future for everyone”.

In Oxford, that comes in the form of a £10m gift to fund Type 1 diabetes research, a cause they have been supporting since 2015. In September, they announced a £10m gift to establish the Bukhman Centre for Research Excellence in Type 1 Diabetes. The Bukhman Foundation has also donated £1m to the Oxford Mindfulness Research Centre.

Wikipedia describes Igor Bukhman as a “Russian-born British Israeli entrepreneur”. In 2022 Playrix announced it was shuttering its operations in Russia and Belarus, whilst maintaining a presence in Ukraine, “due to the continued aggression against Ukraine and in order to maintain its operations”.

David and Simon Reuben

Having a college named after you is perhaps the ultimate vanity project. David and Simon Reuben, through their charitable Reuben Foundation, have achieved that with Reuben College, the university’s newest. It is a graduate college with specialisms in entrepreneurship, AI and climate change.

The brothers are reported to be the third-richest family in the UK, and just like Leonard Blavatnik, much of this fortune was garnered via Russian aluminium smelters in the 1990s. Speculation connected the Reubens’ holding company Trans-World with several murders, but an investigation by Fortune magazine led to a lawsuit and, eventually, a published clarification that “Fortune did not claim and does not claim that the Reubens were responsible for any murders”. A similar Financial Times report stressed that David Reuben “angrily denies any hint that they or their partners had any role” in murders connected with Russia’s second largest aluminium smelter.

The Reubens no longer invest in Russia, but have a chunky UK property portfolio including London Oxford Airport (aka Kidlington airfield). They were awarded the Sheldon Medal by the university in 2022.

Patrick Soon-Shiong

And now for a curiosity. Ten years ago, billionaire doctor and medical researcher Patrick Soon-Shiong announced a £31.2m commitment to cancer research in Oxford. The Oxford University announcement, still live, spoke of a ‘Chan Soon-Shiong Oxford Centre’ which would have “a pioneering role to play in making personalised medicine a reality for cancer patients”.

Nothing has been heard of it since.

Soon-Shiong reappeared in Oxford in May 2024, as the newly appointed chairman of cancer biopharma startup IngenOx. He resigned in December of that year without fanfare. He is rumoured to have held discussions with an Oxford college about a “transformative” donation, but the Clarion has been unable to verify this.

Patrick Soon-Shiong is the inventor of the drug Abraxane, which is used for lung, breast, and pancreatic cancer. With a net worth of $12bn, he bought the Los Angeles Times in 2018; but despite being a major donor to the Hillary Clinton campaign, Soon-Shiong blocked the newspaper's proposed endorsement of California native Kamala Harris in 2024. (Soon-Shiong said he wanted the newspaper to be “less divisive”.)

Stephen A Schwarzman (UKinUSA at Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0) and the newly opened Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities (photo by Roger Close).

Stephen A. Schwarzman

The most visible fruit of billionaire donations in Oxford this year has been the Stephen A. Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities, in the Radcliffe Observatory site between Woodstock Road and Walton Street. As well as the humanities departments and libraries, it features a 500-seat concert hall and café open to the public.

The centre exists thanks to the largest single gift in modern times made to the university from philanthropist and businessman Stephen A. Schwarzman, whose support towards the project now stands at £185m. William Hague, Chancellor of the University, called it “an enormous vote of confidence in the humanities”. Schwarzman himself said: “When announcing this gift in 2019, I shared my belief that the study of the Humanities and Ethics were critical to addressing some of the most fundamental questions society faced, including the impacts of AI. The pace of change since then has only made those questions more urgent.”

Schwarzman is the son of a Pennsylvania shopkeeper, a Yale and Harvard graduate, and is now chairman and CEO of the Blackstone Group, a global private equity firm. Navigating American politics is outside the Clarion’s paygrade, but Schwarzman has supported Mitt Romney and George W Bush, praised Hillary Clinton, and befriended Donald Trump.

In 2019, faculty members and students at the University of Oxford signed an open letter urging it to reject Schwarzman's donation:

“The Schwarzman Centre will be built with the proceeds of the exploitation and disenfranchisement of vulnerable people across the world. In a 2018 report, UN special rapporteur Leilani Farha identified Blackstone as the main contributor to the global housing crisis. Two companies owned by Blackstone are “significantly responsible” for the deforestation of the Amazon, causing untold ecological damage and the displacement of indigenous peoples and the trampling of their collective rights. Closer to home, Independent Clinical Services, an NHS care provider owned by Blackstone, was found to have avoided paying around £3m in tax in 2012 alone.”

He is currently renovating a house and 2,500-acre estate in Hampshire. Local residents were furious to find contractors shipping tankers of water to use in building work, including filling a private lake, during the hosepipe ban in the summer of 2025 (the estate insisted all water was used legally). He also got a warning for over-watering his Palm Beach residence during a drought in 2011, though the estate claims it has been compliant since the citation.

Larry Ellison in 2010 (Oracle PR, CC-BY 2.0); the proposed EIT at Littlemore; artists’ impression of a renewed Eagle & Child on St. Giles.

Larry Ellison

Entrepreneur and philanthropist Larry Ellison is co-founder, chairman and CTO of Oracle, one of the world’s largest software companies. He is so closely identified with the company that Oracle is jokingly said to stand for ‘One Rich Asshole Called Larry Ellison’. His own investing has been shrewd enough to land him (briefly) in 'world's richest man' territory.

His Oxford ambitions have been developing for a while now, but really hit the headlines with the acquisition of the Eagle & Child on St Giles as the de facto Senior Common Room for his Ellison Institute of Technology. The big investment (nearly £1bn) is going into EIT’s massive new science campus in Littlemore, which will house 2m square feet of labs and offices for about 7,000 researchers and staff. Architects Foster + Partners are both revamping the Eagle & Child and designing the campus, which is expected to open in 2027.

National government was sufficiently star-struck by Ellison’s ambitions to finally give the nod to the restoration of passenger service on the Cowley Branch Line. The Department for Transport said in October it will spend £120m to bring the line to fruition, with a direct service to London Marylebone and estimated ridership of 1m passengers a year. There was briefly talk of Ellison commiting £10bn to support the Littlemore campus and its activities over ten years; that amount seems to have been scaled down to a, still astronomical, £2bn.

Ellison is not without controversy. In a 2024 financial analyst Q&A, he said that AI and surveillance technology mean that “Citizens will be on their best behaviour, because we’re constantly recording and reporting everything that is going on.” In an unlikely metaphor, he argues that you can only understand the computer industry if you understand women's fashion (hot themes come and go). Databases might not be hot, but much of the world's important data is in one with Oracle's name on it.

And also…

Michael Moritz is a venture capitalist, former director of Google, and unusually in this list, an Oxford alumnus (he studied history at Christ Church). He has been linked with many of the stars of the internet age, including PayPal, Yahoo, LinkedIn and Stripe. His Oxford donations include a £75m gift to provide scholarships for low-income families; this has now become the Crankstart programme, named after the charity run by Moritz and his wife Harriet Heyman.

Li Ka-shing funded Oxford’s Big Data Institute, aka the Li Ka-shing Centre for Health Information & Discovery, which marshals massive datasets in the cause of medical science. A Hong Kong tycoon with retail, telecommunications, and water interests through his companies CK Hutchison, Hutchison Whampoa, and CK Asset Holdings, he also indirectly owns Oxfordshire’s historic breweries of Morlands and Morrells – both were acquired (and, inevitably, closed) by Greene King, which Li Ka-shing now owns.

Dickson Poon is another Hong Kong magnate, this time making his fortune through luxury goods and martial arts movies. He donated £10m to St Hugh’s to found the University of Oxford China Centre, housed in the impressive Dickson Poon Building.

James Martin was the donor behind the Oxford Martin School; its eye-catching research into climate change and other “pressing global challenges and opportunities of the 21st century” regularly makes the Clarion’s round-up of university news. A Keble alumnus, he founded a succession of IT consultancy firms in the ’70s and ’80s. His £100m donation to found the school in 2010 was, at the time, the largest single donation to the university. He died in 2013 swimming off his private island in Bermuda.

Dame Stephanie Shirley came to the UK with the Kindertransport in 1939 as a child fleeing the Nazis. She wrote that she was determined to 'make sure that mine was a life worth saving'. She founded an all-female software firm (later Xansa plc) while signing letters 'Steve' in a male-dominated industry. Her charitable foundation has so far made grants worth over £67m, including the establishment of Oxford's Internet Institute in 2001. Dame Stephanie died in August this year. Thanks to a Clarion reader who submitted this one.

Persona non grata

Oxford University has a strict donation policy which precludes the acceptance of donations from those involved in illegal or unethical activity: funding terrorism, funds related to tobacco or fossil fuels, or anything where the university would be required to act in an illegal or an unethical way. This policy has caused it to reject or cut ties with previous donors.

Arthur M Sackler (Smithsonian's Freer and Sackler Galleries, CC-BY 2.0); the former Sackler Library (Ralf van Bühren, CC BY-SA 4.0).

Sackler family

In 2023, the University finally relinquished its links to the Sackler family, the American family who owned the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma. Purdue has faced lawsuits regarding over-prescription of addictive pharmaceutical drugs, including OxyContin, and its role in the opioid epidemic in the United States. The Sacklers have been described as the “most evil family in American history”.

The Sacklers’ links with Oxford were, in the main, galleries and positions related to the Ashmolean. The Louvre, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the British Museum also removed the Sackler name from exhibitions.

Nguyen Thao

Linacre College announced in 2021 that it was to rename itself Thao College after a £155m funding offer from Vietnam's richest woman, Nguyen Thao, which would have paid for a new graduate centre and graduate access scholarships.

However, in 2022 Cherwell reported that the donation was under investigation by the UK government due to Ms Thao’s alleged links to the Communist government of Vietnam. The Telegraph later revealed that the donation was blocked by the Vietnamese government due to restrictions on outward donations.

Nguyễn Thị Phương Thảo became a millionaire at age 21 while studying finance and economics in Moscow, where she began distributing fax machines, plastic and rubber from Japan, Hong Kong and South Korea in the then Soviet Union. Since then she has developed a portfolio of business interests, including VietJet and Sovico Holdings. However, Sovico has participated in several oil and gas projects, while the University's donation policy stresses the need for a commitment to net zero by a funder. At the time, the Oxford University Climate Justice Campaign said: “Given that no company involved in fossil fuel extraction or aviation has been able to meet these standards, we seriously doubt whether the Sovico group’s own promise to become net zero represents anything other than greenwashing.”

Rupert Murdoch

In 2024, the University quietly changed the name of a professorship from the ‘Rupert Murdoch Professorship of Language and Communication’ to the ‘Professorship of Language and Communication, endowed by News UK’. It explained the title change was “in order to attract the widest range of candidates” and noted that “the change to the title has the full support of the donor”.

Rupert Murdoch, an honorary fellow of Worcester College, is the former Chairman of News Corp – owners of the Sun and News of the World in the UK, and Fox News in the US. The News of the World famously hacked phone records of prominent people and crime victims, forcing the closure of the paper. Murdoch was also assistant editor of the original Oxford Clarion (the university Labour Club journal) in the 1950s, but we don’t talk about that.

Pecunia non olet

Roman Emperors Nero and Vespasian imposed a tax on the distribution of urine from public urinals, where it was used in tanning and wool production. The tax was used to fill treasury coffers; the phrase pecunia non olet, “money does not stink”, is still used today to say that the value of money is not tainted by its origins.

The streets of Oxford continue to be shaped by philanthropy. Perhaps you, or your neighbours, owe your job directly or indirectly to an eight-figure donation. Perhaps you have been relocated to a university building bearing a donor’s name.

Yet the question of whether billionaires pay their fair share to society has never been more relevant. Oxford’s own global relief charity, Oxfam, says “taxing the super-rich” is essential to tackle inequality. The Green Party’s energetic new leader, Zack Polanski, has called for a 2% wealth tax on billionaires. Meanwhile, Oxford’s rivers are filled with sewage and its bridges are crumbling – perhaps because the Stephen A. Schwarzman Sewage Treatment Plant doesn’t have quite the same ring to it as a world-class humanities venue.

Oxford, like London and Cambridge, is doing better than most. As well as the knowledge and wealth attracted by these billionaire projects, our infrastructure gets a little relief from the developer contributions that come along with them. Blackpool, Barnsley, and even Banbury get none of this.

But perhaps there should be pause for reflection as to the city we are building. An international seat of learning should be a complete ecosystem that benefits and grows around its ‘host’, the City of Oxford, not just a parasite with carved busts of funders and easy access to Heathrow. The Oxford Growth Commission’s interim report, published this week, pointedly called on the University and colleges to “take a wide view about the benefits of development for the City”, citing Christ Church’s responsible ownership policy as a path forward.

Meanwhile, we’d just point out that when Patrick Soon-Shiong wanted to make his mark on Los Angeles, he paid $0.5bn to buy the city’s newspaper. Our inbox is always open.

Further reading

- Donations policy summary for the University of Oxford.