Space Solar – power from above

We’ve written about the emerging climate crisis and the 250 years of Oxford science as evidence. We’ve written about its impact on our gardens. We’ve written how renewable solar energy, one part of the remedy, is planned on a large scale in Oxfordshire but is facing challenges in local planning.

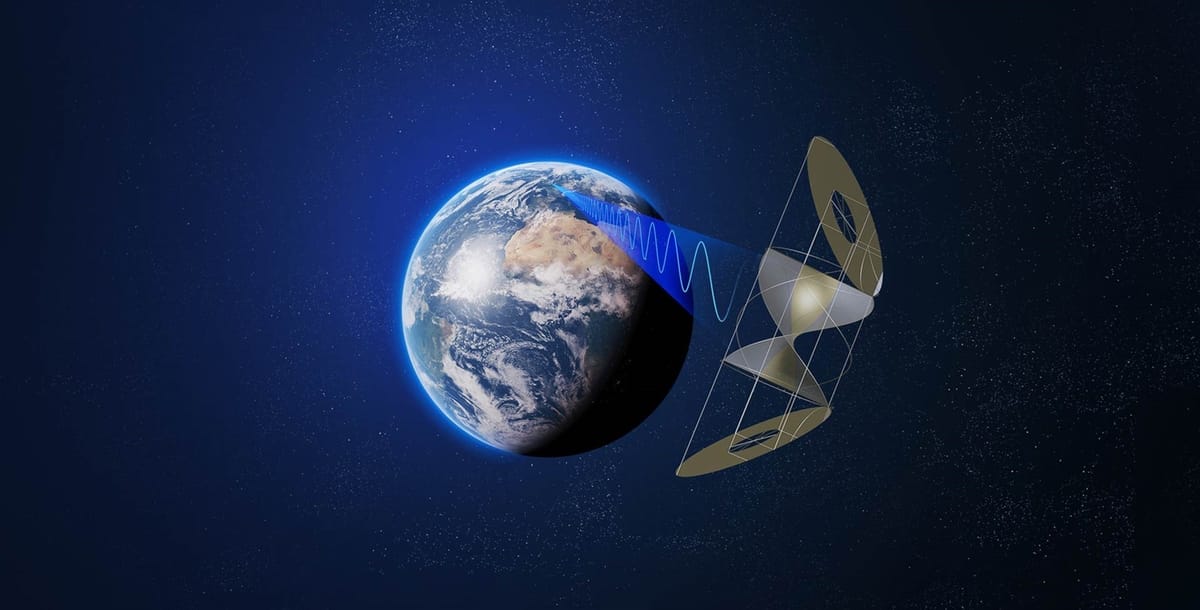

So, what if you could put your solar panels beyond the reach of a District Council’s Planning Committee? What if, even better, that place had 24 hours of sunlight every day? And what if, as a bonus, it had no clouds?

Readers, we are talking about solar power stations in space – 20,000 miles above the Earth – with Oxfordshire company Space Solar showing us the light. We met Co-CEO Sam Adlen and Chief Technology Officer David Homfray at their offices on Harwell Campus. Strap in for lift-off!

Origin story

The idea isn’t new. Science fiction writer Isaac Asimov first described the idea of a space station collecting energy from the Sun and distributing it to planets in his short story ‘Reason’, published in Astounding Science Fiction in 1941. When we met up with Space Solar, they proudly showed us an original copy.

Astounding Science Fiction April 1941; Isaac Asimov's story 'Reason', the first time a satellite solar power station is mentioned in popular literature.

So far, so fantastical. Then in 1968, Peter Glaser at US consulting firm Arthur D Little developed the idea into the ‘Solar Power Satellite’. He recognised that this would need to be huge to gather useful amounts of energy – perhaps a kilometre across. For obvious reasons he wasn’t planning to have wires trailing down from orbit, but rather recognised microwaves as a good choice. He got it patented. A 1970s follow-up study by the U.S. Department of Energy and NASA showed there was potential but several big hurdles to overcome.

From fiction to fact?

First, you have to prove the basic principles. Solar cells have been around for ages (1883, since you ask) and were first used in space on the Vanguard 1 mission of 1958. It’s the wireless transmission of power at scale that needed proving.

Then there is the challenge of designing, launching and assembling a kilometre-wide (or larger) power station in orbit. It’s a structure several times bigger than the International Space Station, which itself required the combined efforts of the world’s four largest space agencies and 13 years to construct.

Why go to that much effort? Because a solar panel in space, above the atmosphere and clouds, and with 24 hours of sunlight every day, can generate 13 times as much power as a solar panel on the ground. And while it might be expensive to launch a power station in space, the cost of climate change is far, far bigger. Maintaining ‘developed economy standards’ with 2°C of global temperature increase will cost $1200 billion a year according to McKinsey & Co, compared to the $186bn annual cost today.

These environmental and economic imperatives, combined with progress on the technical challenges, has led to solar power from space now being considered as a commercial possibility. Space Solar’s CEO Sam Adlen says: “We can deliver baseload power at £30 per MWh (Megawatt-hour – enough to keep a Clarion contributor's laptop running for about 4 years) with today’s launch costs, which is transformational. If costs drop as expected, it will be £10 per MWh.”

Don’t cross the beams!

NASA ran small scale tests in the 1970s that showed wireless power transmission was possible. They transmitted kilowatts over kilometres with the efficiencies that would make space-based solar power commercially viable. Since then, it’s been a case of transmitting more and more power over longer and longer distances.

But increasing the distance of transmission is not the only challenge. With power coming from multiple panels, it is essential to synchronise them so they add up to one synchronised beam rather than cancelling each other out. Space Solar recently showed that they could synchronise and steer a power beam in all directions, rotating through 360° using electronics alone.

Over a gigawatt of power beamed down from space has generated some concern that this could be used as some form of ‘death ray’. Space Solar are quick to dampen those fears. The power beamed down is spread over a wide area and would be one-quarter the intensity of the midday sun. (Organisations in other countries are developing power beaming using lasers rather than microwaves, and these could deliver a more intense beam.)

On the ground, the receiving structure is made of lines of wires held above the surface on poles, almost invisible from a distance. This could be above crops, or even combined with a solar or offshore wind farm. The simple structure opens interesting possibilities: receivers would be cheap enough to be built to receive energy when needed to top-up local needs. The satellite beam can be switched quickly to wherever the power is needed (or wherever offers the highest price). This could one day replace burning gas for short-term electricity peaks, so we no longer need back-up power stations on standby for the increasingly limited time they are needed.

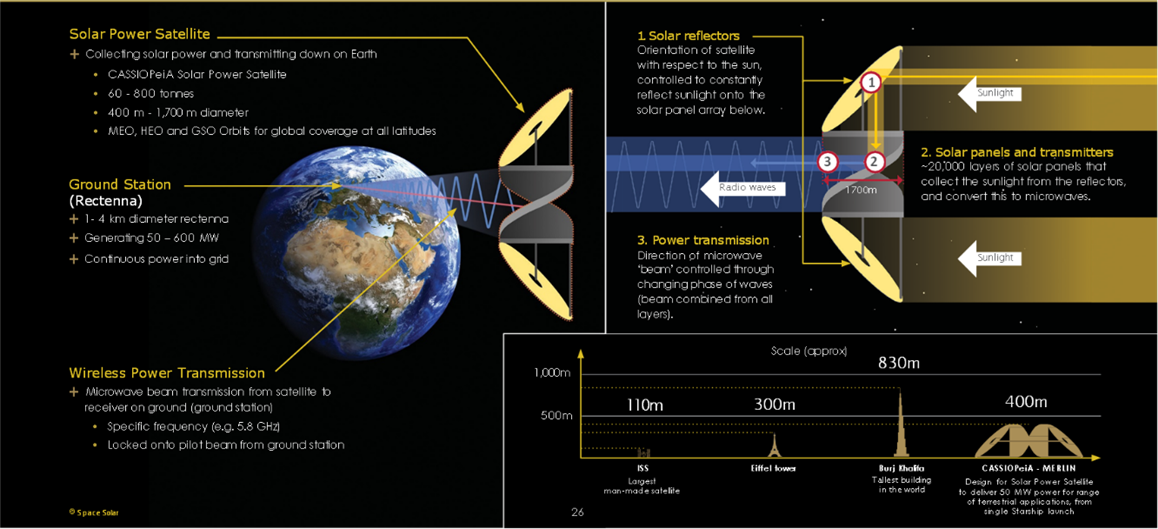

That’s no Moon

The full-scale power station envisaged by Space Solar is a design called CASSIOPeiA: Constant Aperture, Solid State, Integrated, Orbital Phased Array (first proposed in 2016 by Ian Cash). The full-scale version would be 4km long, 1.4km wide and with a mass of 800 tonnes (physics ed: mass not weight). It has two large mirrored discs at each end, reflecting light at the spiral-shaped central section, which holds 20,000 solar panels and microwave transmitters.

A key part of the design is that the reflectors concentrate light from a wider area, increasing the efficiency far beyond an Oxfordshire-based panel. This helps answer environmental concerns about the rocket launches. The savings from needing fewer solar panels to generate the same electricity mean that a solar power station will be better in terms of greenhouse gas emissions after 23 days of operation – if, that is, it is launched using carbon-free fuels. Space Solar also claims that it uses only one-thousandth of the critical minerals, because of its generating efficiency and because its 24/7 power reduces the need for storage batteries.

The falling cost of those rocket launches is the other big enabler of the project. 20 years ago, it cost $20,000 to put one kilogram into orbit. It now costs $2,000/kg with SpaceX’s Falcon 9 – and that’s likely to fall even further due to competition between the (much larger and more reusable) SpaceX Starship and the Blue Origin New Glenn. Space experts expect capacity to rise and prices to tumble, not least because company founders Elon Musk (SpaceX, Tesla) and Jeff Bezos (Amazon, Blue Origin) are famously competitive.

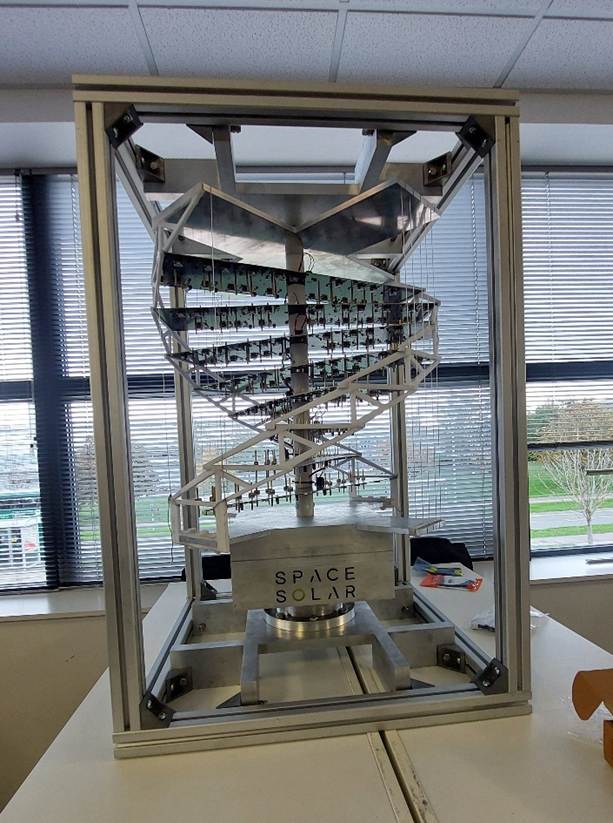

Assembling the beast is a whole other game. How do you assemble something the size of a market town when there isn’t even ground to stand on? And isn’t something that big going to be hit by meteoroids or space debris at some point? Planning for this, Space Solar engineers have developed a design that is highly modular, assembled like a giant construction set in space by robots, and the robots can replace any units that break down.

Space Solar have been testing this with UKAEA’s RACE robotics division at Culham. Chief Technology Officer David Homfray showed us the test rig in the office. He described how the robots are designed to replace broken sections and even climb over each other if necessary. (No humans will be on site, so every eventuality must be planned for.)

He explained that it is difficult to test robots built to work in zero gravity on the Earth: they are simply not designed to lift things against gravity. So you can understand why Space Solar is pleased that Satellite Application Catapult has a new Gravity Offload System, built to take the weight. This will enable Space Solar, and a rising wave of in-orbit service and assembly missions, to test their kit in a more representative situation.

To credibility and beyond

You don’t jump from ground tests straight to the huge satellite that Space Solar envisages. Instead, they plan to move from tests of power beaming from drones, to a 1MW space demonstrator, to a system that provides power for polar regions that would fit in a single Starship launch. Only then will they move to grid-scale power satellites.

Space Solar’s research so far been funded by grants and private investors, supported by partners including MDA Space and Thales Alenia Space. They are now looking for investors that will help them to take the tests into orbit.

Is this (literally) pie in the sky? Are solar power stations in space really the answer to our rising energy needs? A recent study led by Dr Wei He at King’s College London reckoned it could play a ‘pivotal role’ in the transition to renewable energy. This is because it will provide constant reliable power, potentially reducing the need for battery storage by two-thirds (full paper).

Professor Henry Snaith from Oxford University agrees, but believes space-based solar power will not be large enough quickly enough to be a big contributor to humanity’s 2050 Net Zero target: he argues it is more likely to be a technology for energy needs after that.

Homfray takes a surprising perspective on this. Although we’ve been talking about harnessing invisible energy, he wants to talk about physical material instead. “In the next ten years, to achieve the energy transition, we’re going to be digging more rare minerals out of the ground than ever before. If we don’t use them responsibly, we won’t have enough.” He points to an International Energy Agency (IEA) report, ‘The Role of Critical Materials in Clean Energy Transitions’.

Space Solar have set their sights high and want to be shaping that transition. It is another example of how the Oxfordshire innovation ecosystem has brought together big ideas with the capabilities that might just be able to bring them to fruition, subject to the practical and funding difficulties that so many UK innovators face between research and commercial success. We’ll watch their progress with interest – and you can watch their 3-minute video now.