The street in the National Cycle Network where cycling is banned

You might have thought a fundamental tenet of a National Cycle Network would be that you could ride a bike along it. In Bicester, that isn’t the case.

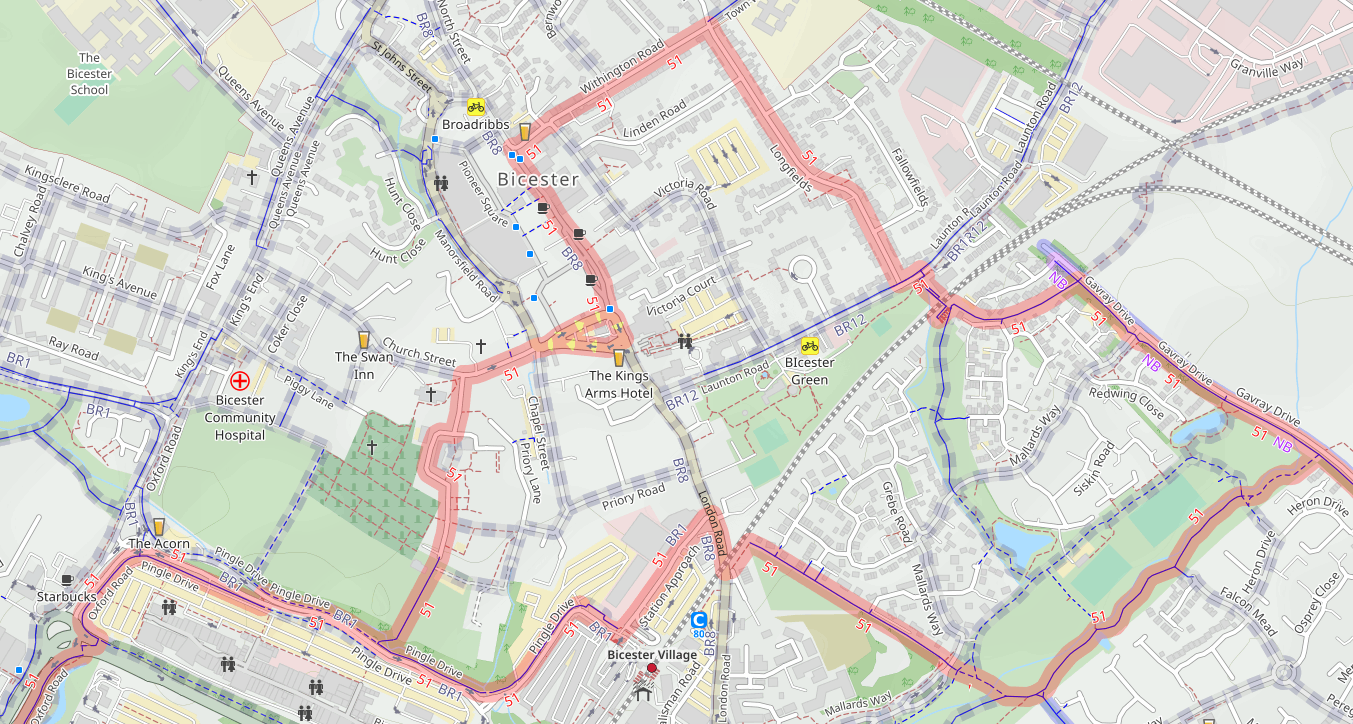

The Varsity Way is the official signposted cycle route from Oxford to Cambridge. Blue signs with the number ‘51’ on them point cyclists along back streets, cycle paths and country roads from Broad Street to the banks of the Cam. But on Sheep Street in Bicester, you’ll have to get off and push.

One of the town’s main shopping streets, it is up to 25m wide in places, and never narrower than 10m: in other words, between four and ten buses wide. It was pedestrianised in 1994 in an attempt to keep Bicester’s town centre vibrant in the face of competition from nearby towns – and from the Bicester Village retail park, under construction at the time and opened the following year.

On that score, it has failed. Just a few name retailers are left on the street: Boots, Superdrug, Iceland. Charity shops dominate, plus vape stores, bookmakers, phone repair and a Wetherspoons. A recent post to the Bicestorian Facebook page contrasted 2024 with 1978, “when not a single unit was boarded up or empty, people shopped locally, and local businesses thrived – a far cry from the town centre of today!” It’s best seen on a Friday, when a small street market is held. Meanwhile, the two edge-of-town developments, Bicester Village and Bicester Avenue, go from strength to strength.

But despite the changing fortunes of the street, one thing has remained constant: a 24/7 ban on cycling.

The National Cycle Network

In her new book about the National Cycle Network, Potholes and Pavements, journalist Laura Laker lists the many challenges it faces. Unlike the country’s Government-funded road and railway networks, the NCN is run by a Bristol-based charity, Sustrans, which is reliant on sporadic and short-lived grants. She explains that urban areas like Bicester have particular issues:

In built-up areas the NCN was often of mixed quality, requiring some skill and confidence to navigate, and hardly attractive to a novice… in places, councils didn’t seem to know the NCN existed. Sustrans couldn’t make councils build, maintain or improve routes.

She recounts how the network’s aims are to be “attractive for novices, memorable for visitors, and useful for local cyclists”. Routes should be safe enough for a confident 12-year old.

The National Cycle Network was first set out in the 1990s with the help of a Lottery grant. Its Oxfordshire routes join together towpaths, old railways and (mostly) country lanes to link the county’s major towns. It’s rarely the quickest way by bike, but for journeys such as Oxford to Abingdon or Didcot to Wantage, it’s the most enjoyable and the safest. In Bicester, it’s none of these.

The NCN in Oxfordshire is looked after by groups of volunteers. Richard Fairhurst, co-ordinator of the group for Bicester, says sending the route another way through the town doesn’t work:

The situation on Sheep Street means we’ve actually signposted an alternative route via Langford Village to Gavray Drive. That’s safe enough, but if you’re just going to send cyclists through a housing estate, what’s the point of going through Bicester at all?

If the Oxford–Cambridge cycle route is to go through Bicester then we want to give people a chance to visit what’s otherwise a lovely town centre, and for that, it has to be Sheep Street. The traffic is too heavy on Launton Road or Manorsfield Road for non-confident cyclists, and sharing the narrow pavements with pedestrians is something no-one wants, especially pedestrians themselves.

A wolf in sheep’s clothing?

Earlier this year Oxfordshire County Council, after 30 years of the bike ban, took the view that Sheep Street’s ten-bus width could conceivably accommodate cyclists safely. It opened a consultation on whether to, experimentally, allow cycling along the street. Responses were mixed.

Replying to the consultation, Thames Valley Police said “Sheep Street is a very wide area which, personally, I feel can more than accommodate pedal cycles and pedestrians sharing use of the area”. Bicester Bike Users’ Group, as you would expect, also supported it:

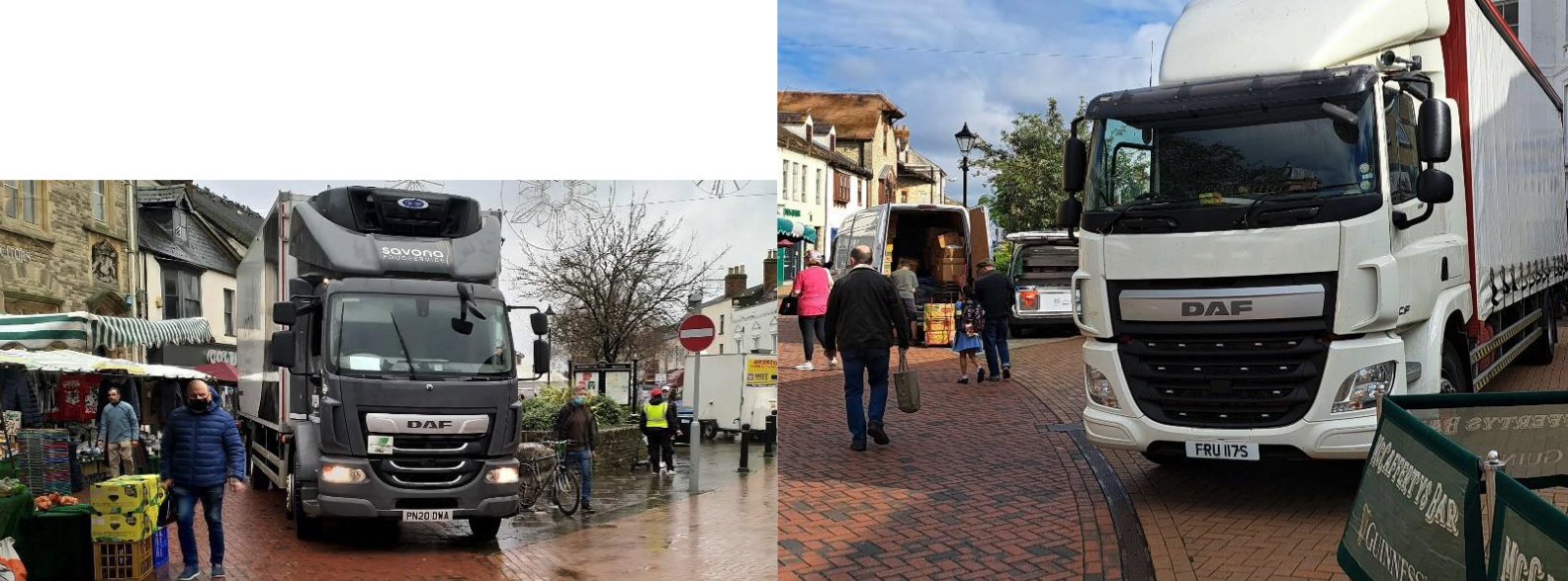

The perceived risks to pedestrians from cyclists are generally greatly exaggerated. In around 25 years, despite cyclists actually using Sheep Street despite the prohibition, there has only been one minor reported accident on Sheep Street, involving two teenagers. The current situation is completely inconsistent and coherent: far more dangerous and heavy vehicles such as trucks, vans and private vehicles are permitted to drive along Sheep Street even during market hours.

One business owner said “I support the introduction of pedal cycle access” while another said “We believe this will have a negative affect on the town centre.” The organisers of the Friday market requested that “cyclists are not allowed in the street on market day”.

The two strongest voices in opposition came from Bicester’s two Conservative county councillors, Michael Waine and Donna Ford. Responding to the consultation, Cllr Ford said “A full public consultation is necessary before making such a major change”, while Cllr Waine told the OCC meeting in April considering the consultation report that “Pedestrians have been sidelined and not consulted. This is a major infringement of democratic rights.”

Consequently the meeting saw Cllr Andrew Gant, Oxfordshire County Council’s cabinet member for highways, defer the decision for further consultation as “this is what the local councillors have asked for”. The consultation period now closes this Saturday, 31 August; the survey now includes a question asking if cyclists should dismount on market days.

“Shouty headlines”

OCC has a target of “reducing 1 in 4 current car trips by 2030”. In Potholes and Pavements, Laura Laker asked Chris Boardman, former Olympian and now head of Active Travel England, how change like this could be achieved.

In representative polls, between two thirds and four fifths of people support this agenda. Then the local consultations come around and we disproportionately hear from those on the extreme ends. The debate, from there, is held in shouty headlines decrying council overreach. Chris believes the rest of us are quietly getting on with our lives, supporting quieter, cleaner, safer streets without writing angry letters or social media posts, and often not responding to consultations. He wants to represent the majority, not just the loudest shouters.

Sheep Street is just one road, but to the county’s cyclists, it is a litmus test of whether Oxfordshire’s councils and residents have the appetite to improve cycling provision outside the city. If a 25m wide street remains open to delivery drivers but closed to cyclists, the 1-in-4 target seems certain to be beyond reach.