Time for Oxford to organise

With the far right hogging the headlines, Oxford trade union activist Toby James says the city can buck the trend – but only if we work together, from allotment associations to school governors to community music…

There's a Kurt Vonnegut quote:

“What should [...] people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.”

It may be familiar to some readers. These words used to hang on the wall of Jericho Coffee Traders in the High Street. I didn't put them there – but that's where I found them, and something in this sentiment stuck with me.

Where are our communities now? Shattered somewhere among the broken porcelain and coffee dust on that café’s floor, I'd say.

Britain is fractured – this is clear. It's maybe the only truth recognised across the Overton window. This is my thesis: the only way to rectify this is to reorganise. Organise in the sense of building connections, relationships, communities. Organise in the sense of organised labour.

The state we’re in

There is a tendency among modern progressive movements to look immediately to the state for solution. But there is a flaw in this. There are limits to state power. No amount of governmental hocus pocus can mandate you into trusting your colleagues or your neighbours.

And actually, the government has often made a reasonable go at ensuring some baseline standard of living for all. It's us, as wage earners, who've fallen short. We’ve failed to hold up our side of the collective bargain.

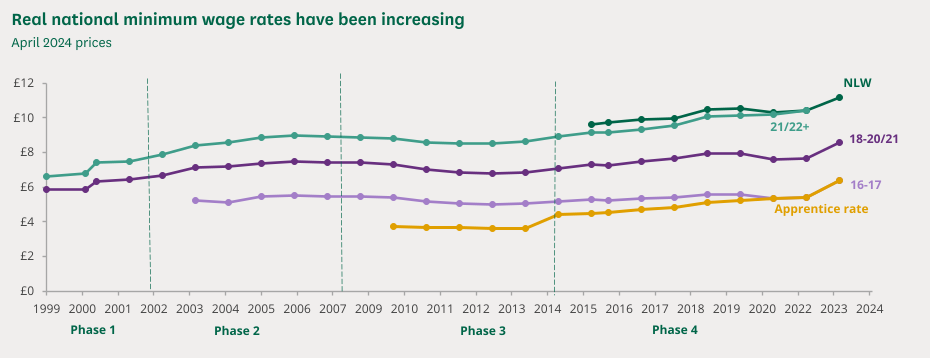

Nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than in wage growth this century. Much is made of the astronomical increase in the pay of CEOs, directors, and various other bogeymen. But there is one – and only one – other wage band that has done fairly well against inflation over that period. That's minimum wage. And yes, this includes under the 14 years of Tory government from 2010, albeit with a blip after the financial crash.

Meanwhile, the median university graduate, in Oxford as anywhere else, is closer to minimum wage than ever before. Most people have received below-inflation pay rises for years. Nationally, pay scales are being squeezed, collapsing into a sticky blob propped up by a creaking legal minimum.

Why is this? The simple, or trite, answer is the decline in trade union membership, and it is broadly correct. But there is a crucial nuance to this: it is really the collapse in collective bargaining coverage that is the issue, not just the spiralling membership percentages.

We want to be together

Collective bargaining is the process by which wage earners improve their conditions. You can find it in the market dynamics of labour, and the nature of employment. It comes in a few shapes, all of which are built on a power calculus between employees and employer.

Its initial principle is the same one that drives an employer to raise the salary of a post they’re struggling to fill. If the employer is struggling to fill that post because all possible applicants have agreed with each other not to take work below a specific rate, that’s collective bargaining.

In employment, staff earn more money for their employer than they take home in wages. This confers on workers a huge amount of power to bring employers to heel.

It is a difficult power to invoke. Individually, you are easily replaceable – some people more so than others. This power can only be wielded collectively, by entire workforces against an employer. And this is difficult. It is a tangled cat’s cradle of interests and needs. This is collective bargaining – the implicit threat of the strike, the necessity for an employer to heed the collective.

In law, a union can seek recognition of its collective bargaining rights by an employer. If the union can demonstrate support of the majority of the workforce, this recognition is given, whatever the boss has to say about it.

Great!

Well, sort of. Let’s not pretend that this magical threshold, that fabled 50% of support, makes worker power a done deal. (If we did pretend that, we wouldn’t be the first. We’d be in pretty good company, in fact. This is where trade unions as institutions have fallen short consistently for decades – and in some parts, forever.)

Collective bargaining isn’t signing up to let a trade union official negotiate your conditions for you. Collective bargaining isn’t being a lone union member in a workplace, with a remote rep on hand to stand by your side while the boss makes you redundant. Collective bargaining isn’t paying your subs out of charity, or signing up for the pension scheme, the insurance, or the discount codes for the local gym.

Collective bargaining is engaging with your colleagues, building a collective together, reaching compromises with each other if not with your employer. It is putting effort in. It is taking an active interest in your workplace, one at least equal to the size of its interest in you.

Unless you are willing to sign up to every pay scale in every company being set by central government, collective bargaining is the only route to better conditions or higher pay in the workplace.

“There is nothing more valuable than connection”

Here is a point made many times: anything a government gives you, the next can take away. This is true, and it is often made to highlight the need for changes to be won. Won through collective action, struggle, however you want to put it. It highlights the need to build a collective capable not only of winning in the moment, but also holding firm into an uncertain future. But building these collectives is an end as much as a means.

In an increasingly isolated world, a world of remote work and self-employment, bogus or otherwise, there is nothing more valuable than connection. Yet throughout our country, people are jumping to the politics of individualism, closing in and turning away from our communities. It is perhaps understandable in the face of declining living standards and an uncertain world – but it is a vicious cycle.

Earlier this year, I was at a talk in London by a US political organiser. He said that the 2024 Democratic US presidential campaign found that a key indicator for someone’s political leaning was the size of their friendship circle. The wider someone’s social life reaches, the more progressive their politics. But with the price of a pint stubbornly buoyant above a fiver, and a coffee not much below, where are people meant to make these connections? In the 20th century, working men’s clubs and social clubs (and, indeed, Clarion walking and cycling clubs) were founded in reaction to these same pressures. Oxford is wonderful for this – we still have a rich selection of accessible and affordable civic spaces. But we must not take them for granted.

And this is the nub. If you believe there is anything worth defending in society, then defend it. It requires active participation from all of us, building and strengthening relationships, decentralizing ideas and power. Community isn’t a player piano, it’s an orchestra, and it needs you on the timpani.

If the kids are united

I've elided one word in that Vonnegut quote. He specifically talks to young people. There’s a truth in this that he may not have intended. Progressive politics may often appear a folly of youth, but trade union membership, and civic engagement, are not. As society’s shape evolves, younger people find themselves stretching for a housing ladder they can’t reach, lost in a barren job market, and staring down a terrifying climate future. And yet their engagement in their unions, or in the organs of their society, are muted at best.

If society as a whole cannot engage Gen Z and Gen Alpha, we are all, as they would put it, cooked.

So put into practice, what does that mean? It means going to Bossaphonik. It means volunteering to sit on your local allotment committee. Run to be a governor of your kids’ school. Yes, join a union – but join the union and put the work into building the strength to make it worthwhile. Organise your workplace. Organise a workplace social. Vote – in local and national elections, but also in trade union ballots. See what’s happening at Florence Park Community Centre. Volunteer with a charity, go to the local swimming pool, play at an open mic night.

Britain is in a parlous state. But latent within our towns, cities, and workplaces, is a power that we can use to fix it. And now it falls to us to harness it. It falls to us to reorganise.

Toby James is Oxford Labour’s Trade Union Liaison Officer.