Oxfordshire’s road safety crisis

It is a mark of the road safety crisis in Oxfordshire that, while we were writing this piece, news came in of another cycling death on a county road.

David Brain, 54, died on Saturday while cycling on Frieze Way, near Kidlington. It was one month, to the day, after Tim Joss (60) was killed cycling between Brize Norton and Witney.

Then, on Monday, a teenage girl was taken to hospital in a life-threatening condition after a collision outside Oxford Brookes.

Tim Joss, founder of an arts charity, was described by his widow Vivienne Parry as “unfailingly modest, but a man of strong principles and values… his love was warm, unbounded and generous”. David Brain was called a “gentle soul” with “a heart of gold”.

It’s against this backdrop that Oxfordshire County Council’s Vision Zero strategy goes out to consultation. Council leader Liz Leffman announced a commitment to Vision Zero – “a strategy to eliminate all traffic fatalities and severe injuries” – in March 2022. This, too, followed two cycling deaths: Ling Felce was cycling across The Plain roundabout in East Oxford, Ellen Moilanen was cycling past Oxford Parkway.

But what levers can the County Council pull to prevent these deaths? Is it achievable by the council alone – or do we need a wider change in mindset?

Brize Norton

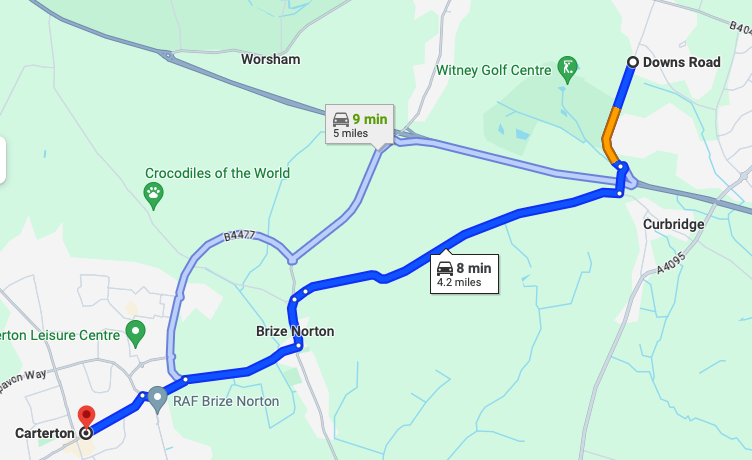

It was on the Carterton to Witney road, via the village of Brize Norton, that Tim Joss died. It is just five miles between the two, West Oxfordshire’s largest towns. In other countries – even in London, or Cambridgeshire – this would be a journey which hundreds of commuter and everyday cyclists would expect to make regularly, and safely.

In Oxfordshire, the roads are twisting. Traffic is fast. Segregated cycle tracks are rare, other than an occasional converted narrow pavement.

Carterton to Witney is not unique in having no safe cycle route. The same is true of Wheatley to Oxford, Eynsham to Botley, Adderbury to Banbury, Thame to Haddenham station, and many more.

Carterton to Witney, however, is unusual in that a cheap, ready-made solution is available. In 2018, a new roundabout opened in West Witney, connecting a distributor road to the A40. According to Google Maps’ traffic estimates, it is now only one minute slower to follow the main A40 and B4477 Carterton access road than to take the minor road through Brize Norton:

Witney’s community bike project, the Windrush Bike Project, proposed in 2020 that the old route should be reserved for pedestrians, cyclists, and property access.

There is a solution that could be implemented within weeks rather than years, and it’s been made possible by the building of the Downs Road–A40 roundabout. With the new junction there are now two parallel travel routes between Brize and Curbridge [on the outskirts of Witney]. By closing one to motorised traffic except for access, it creates a direct, low traffic route for cycling at a very low cost.

The concept would be minimally disruptive. Car journeys would be slowed by one minute. The two buses per day which use the road could take the A40 route.

Yet it’s fair to say the idea did not win universal acclaim. Suzi Coul, formerly a West Oxfordshire district councillor and currently an aide to Dominic Raab MP, posted to the Carterton Community Facebook group last year:

Among the 138 Facebook comments were “Whàt a load of shite too many cyle lanes now no devil uses them”; “What a stupid idea it's something I would expect from Oxford tree huggers”; “This post proves to do proper research before posting. Trying to cause trouble on something that isn't true thats all it is.”

(The posting was indeed incorrect: at no stage did Oxfordshire County Council “go through the motions to close the road”.)

Oxfordshire County Council says it has an alternative plan. A spokesman told the Oxford Clarion:

We send our sincere condolences to the family of the person who died in this incident. While we must wait for the police to investigate the cause, tragedies like this focus minds on the vital importance of making our roads and streets safer for all users – especially the most vulnerable.

The Witney LCWIP [Local Cycling & Walking Infrastructure Plan] – a wish list of projects which could improve the town’s active travel network, reduce the reliance on single use motor vehicles and cut congestion – has identified Witney Road between Carterton and Witney as a potential scheme to deliver a two-way segregated cycle track. This would be a major scheme and, due to the volume of work required is described as long term and would require significant funding.

We also plan to draft an LCWIP for Carterton during 2024/25 and continue to seek funding towards cycling schemes in the area.

Vision Zero

The County Council explains Vision Zero simply. “No human being should be killed or seriously injured as the result of a road collision, whichever mode of road transport you are using.” It aims to eliminate road deaths and serious injuries by 2030 in the largest towns, and by 2050 across the county.

To do this, it will look for clusters where most collisions have taken place. A £4m budget, over three years, will be spent on safety improvements at dangerous roundabouts and other “hot spots”. Roundabouts in Oxford, Didcot and Witney have already been shortlisted.

It will look at reducing speed limits in rural areas, potentially enforced with average speed cameras. It will create more traffic-free School Streets, review road design in new housing developments, and launch a campaign to encourage “behaviour change” among road users. It will require its own contractors to sign up for safe HGV schemes.

The strategy is out for consultation now.

£4m is not a large budget. It’s enough to make meaningful improvements at a few locations. But 2030 is not far away. To get from “reduced deaths” to “zero deaths” in Oxford alone would require significant investment. To achieve it across Oxfordshire would be many times more. Neither of the roads in the two latest cycling deaths had been identified in OCC’s initial works list.

A shift in thinking

Robin Tucker, from Oxfordshire Cycling Network – the body that represents the county’s cycling campaigns – says we need a change in mindset.

“The main thing is not to accept that deaths on the road are acceptable or inevitable – it’s a shift in thinking. You just don’t accept the ethics of saying ‘killing happens’, and leaving it to happen again. It's very much like the approach you see in the aviation or rail industry – whenever there is a crash, or even a near miss, you investigate it, learn from it, and use that to reduce the chances of it happening again.”

But he cautions that OCC is constrained by funding.

“To some extent they have the tools – they can redesign roads, they can reduce speed limits. But they have limits – they don’t have much funding, some of which is in their control and some is not, because central government tends to micro-manage infrastructure bids. While the money put into Vision Zero is great, it’s a fraction of, say, the new slip roads planned for the A34 at Lodge Hill.”

The congestion-busting Lodge Hill works, which add two new slip roads to the existing junction north of Abingdon, are expected to cost over £33m. The ‘HIF1’ road project from the A34 to Didcot and Clifton Hampden is priced at £279m. £180m is being spent on the A40 between Witney and Oxford.

A segregated cycle track along the Witney to Carterton road, as envisaged by OCC, would typically be priced at £3m–£5m. It is a small fraction of the cost of the road schemes. But OCC admits that funding will not be available until the “long term”. The Windrush Bike Project’s proposal, which would come in at less than one-tenth of the price, could be implemented now.

Frieze Way near Kidlington, where David Brain died, is a relic of a former road layout. Built in 1961 as a dual carriageway to carry what’s now the A34, it was superseded in 1990 by the flyover at Peartree. It now serves as a local access road to Kidlington, much larger than it needs to be. Last year, cycling groups suggested inexpensively carving out a bike lane on each carriageway, or repurposing one entire carriageway.

Why hasn’t this happened? The answer, perhaps, lies in Suzi Coul’s Facebook post. A county council bruised by the ongoing traffic changes in Oxford is understandably wary of creating a further furore. No matter that the actual effect on motorists would be a barely discernible increase in journey times. No matter that the budget exists already. There is still a strong strand of opinion that thinks “too many cyle lanes now no devil uses them”.

“Life can never be exchanged for other benefits”

But how representative are Facebook comments?

In the Netherlands 50 years ago, a rising tide of road deaths was halted by a shift in public opinion – or by those who already believed in road safety finding their voice. These voices empowered the country’s government to rethink the way it designed roads and cities. As a Guardian history of Stop de Kindermoord (“Stop the Child Murder”) explains:

“I was a young mother living in Amsterdam and I witnessed several traffic accidents in my neighbourhood where children got hurt,” Maartje van Putten, 63, recalls. “I saw how parts of the city were torn down to make way for roads. I was very worried by the changes that took place in society – it affected our lives. The streets no longer belonged to the people who lived there, but to huge traffic flows. That made me very angry.”

Van Putten remembers the 70s as a time when Dutch authorities were remarkably accessible: “We simply went to tea with MPs – and they really listened to what we had to say. We cycled with a group of activists and an organ grinder to the house of the prime minister, Joop den Uyl, to sing songs and ask for safer streets for children. We didn’t get beyond the hallway, but he did come out to hear our plea.”

Robin Tucker stresses that achieving Vision Zero is not just a job for the County Council.

“These efforts really work best as a partnership, where the council, the police and local transport stakeholders are all working together to get changes done and to get the message out. That’s what is happening in Surrey and in Essex; you think of them as car-dominated counties, and in many ways they are, but they are still leading the way on making their roads safer through Vision Zero.”

Wikipedia describes Vision Zero as prioritising life above all else:

A core principle of the vision is that "Life and health can never be exchanged for other benefits within the society" – rather than the more conventional comparison between costs and benefits, where a monetary value is placed on life and health, and then that value is used to decide how much money to spend on a road network towards the benefit of decreasing risk.

This may be uncomfortable for some in Oxfordshire. It changes the balance in favour of repurposing the Carterton to Witney road, or the surplus capacity on Frieze Way. It suggests that the 2014 decision to prioritise bus throughput over road safety at The Plain roundabout should be rethought.

It is not yet clear that Oxfordshire – the county, its council, but most of all its people – has the courage to take that step. Until it does, we will continue to report deaths on the county’s roads.