What does the Strategic Defence Review mean for Oxfordshire?

Last month, the UK Government published its Strategic Defence Review (SDR). A wide-ranging document, it has the aim of making Britain stronger and safer, as well as resetting the UK's approach to defence in the face of what it calls a ‘generational’ defence and security challenge.

The Government has pledged to implement all these recommendations – although critics question where the resources to meet the requirements of the SDR will come from, despite government pledges to raise defence spending levels.

The SDR has significant implications for the county, obvious and not so obvious. Military presence in the county isn't the scale it once was. Famously, Heyford Park and Harwell were once military but are now, respectively, a mega-development of 700 new homes and amenities, and a science campus – though traces of the past still exist.

But Oxfordshire still has a large military presence. More than 11,747 military personnel (2019) and an estimated 3,500 families live and work in the county at bases including Brize Norton, Abingdon, Bicester and Benson. The implications of the SDR go much deeper, and seek to blur the lines between civilian and military in a ‘whole country response’ in the event of war. They aim to move to warfighting readiness in part by using the best of civilian innovation, investing and growing the UK economy. Given Oxfordshire's known capability for innovation, and its position at the heart of the UK's Modern Industrial Strategy, we took a look at the likely implications of the review for the county.

But first, some background…

This self proclaimed first-of-its-kind Strategic Defence Review was launched by the Prime Minister within two weeks of the General Election. It contends that the world has changed:

“The threats we now face are more serious and less predictable than at any time since the Cold War, including war in Europe, growing Russian aggression, new nuclear risks, and daily cyber-attacks at home.”

The SDR is the response to those threats. It sets out these ambitions:

- 'NATO First’: stepping up on European security by leading in NATO, with strengthened nuclear, new tech, and updated conventional capabilities.

- Move to warfighting readiness: establishing a more lethal ‘integrated force’ equipped for the future, and strengthened homeland defence.

- Engine for growth: driving jobs and prosperity through a new partnership with industry, radical procurement reforms, and backing UK businesses.

- UK innovation driven by lessons from Ukraine: harnessing drones, data, and digital warfare to make our Armed Forces stronger and safer.

- Whole-of-society approach: widening participation in national resilience and renewing the nation’s contract with those who serve.

So what might change?

Forces accommodation

The most obvious impact of the SDR is on existing military personnel in Oxfordshire. A 2023 report by the Defence Select Committee found that two-thirds of Service Family Accommodation (SFA) was “essentially no longer fit for purpose”, and warned of its impact on recruitment, retention, and morale in the Armed Forces. Carterton, the hometown of RAF Brize Norton, has been no exception to this rule.

The government unveiled a new charter to upgrade SFA in April 2025. The SDR reiterates that commitment, which will please Banbury MP Sean Woodcock who has long campaigned for an improvement in military housing. It commits to:

“[…] a generational renewal of military accommodation, with at least £7bn of funding in this Parliament— including over £1.5bn in new investment for rapid work to fix the poor state of forces family housing.”

Brize Norton

The SDR says the future of the RAF lies in accelerating its adoption of the latest technology and innovation, learning from some of the targeting and drone technology being developed in Ukraine. It pledges to create a next-generation RAF, with F-35s, upgraded Typhoons, next-generation fast jets (whose HQ has just opened down the road in Reading), and autonomous fighters to defend Britain’s skies.

As such, RAF Brize Norton has the honour of being one of the few bases mentioned in the SDR, cementing its importance at the heart of the British military as its main air transport hub:

“RAF Brize Norton should be a high priority for investment and improvement in partnership with private finance, as part of a new partnership with industry. Given it is not affordable to establish a military alternative to Brize Norton should it be unavailable for operations, alternative commercial facilities must be planned and, if necessary, legislated for under the new Defence Readiness Bill.”

Brize, therefore, continues to be critical to UK defence and warfighting readiness – though the oblique reference to “should it be unavailable for operations”, particularly given the recent Palestine Action incursion to the base, might give local residents some cause for concern.

Defence innovation as an engine for growth

The corporate world often talks about ‘innovate or die’. In the military this may be taken somewhat more literally. AI and cyber are now warfighting domains. In the past the UK sought overwhelming force on land, sea and in the air; now we must add at least these two to the list.

The vision of the SDR is that, by 2035, UK Defence will be

“A leading tech-enabled defence power, with an Integrated Force that deters, fights, and wins through constant innovation at wartime pace... Advantage on the battlefield will not come from a single technological advance but from the combination of existing capabilities and a range of emerging technologies.”

One term we're all going to have to get familiar with is ‘dual use’. A drone that takes beautiful aerial shots at a festival is fundamentally the same technology used lethally in the trenches in the Donbas. A satellite like the Earth Observation satellite can be used to look for ‘grey belt’ land, where houses might be built, or to assess deforestation in Brazil... or military supply build-ups close to a a foreign border.

So while recent innovations may have come from within the military or from traditional military partnerships, the SDR outlines a radical change of approach in order to move to warfighting readiness more quickly. Specifically, it advocates drawing on commercial solutions in partnership with British industry, sharing problem sets with industry – not product specifications, which would be a significant change to military procurement.

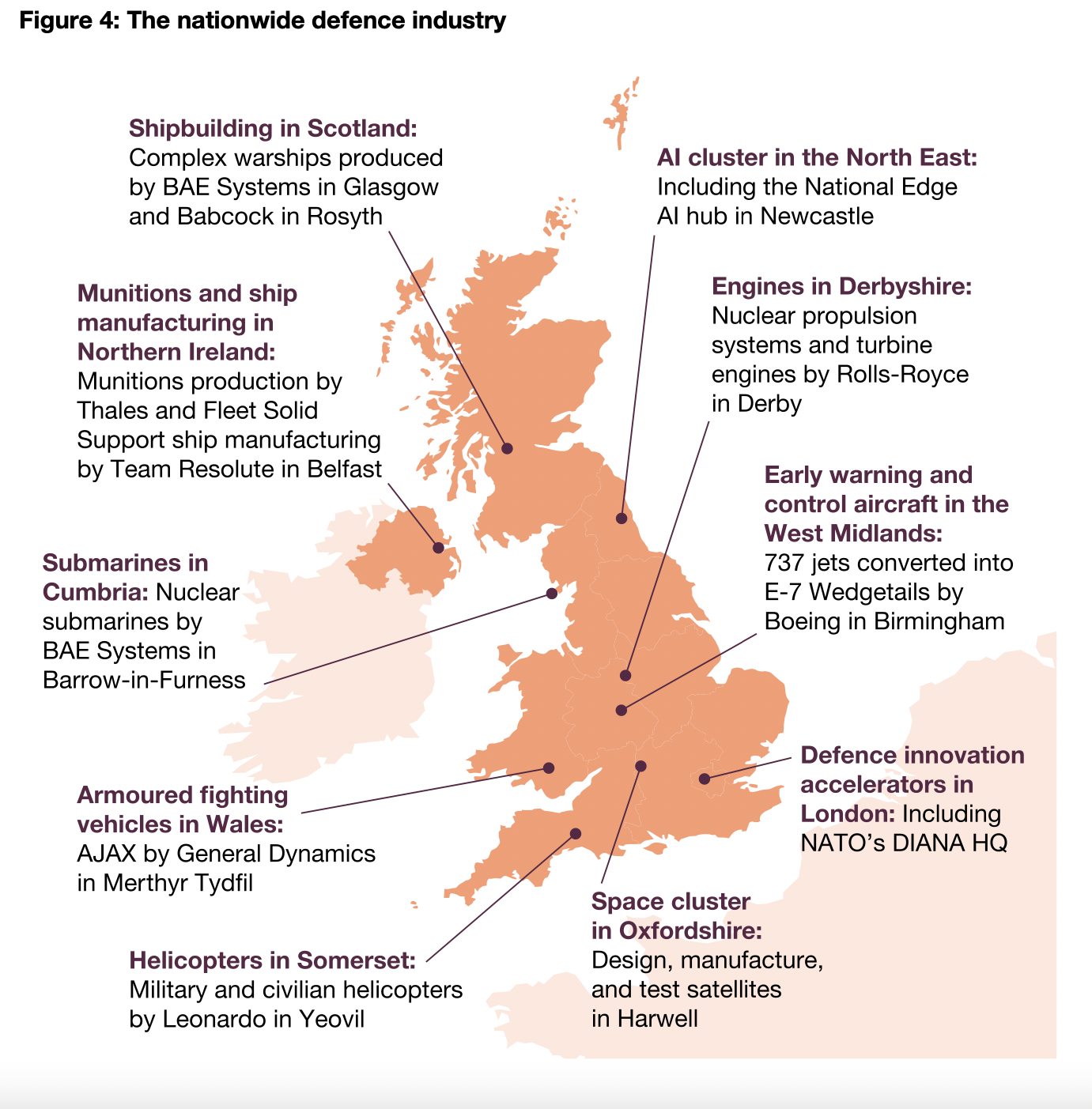

The defence industry has traditionally been with large companies like BAE, Airbus, with only 4% from SMEs. The Ministry of Defence, recognising that innovation can come from smaller firms, has plans for new targets and a support hub. All of this should benefit small tech firms in Oxfordshire, including those that don't even exist yet. This means working with startups, scale-ups, and spinouts, particularly in the tech sphere as well as innovation organisations, private equity, venture capital, and other investors within the UK and NATO member states.

It also speaks to developing regional clusters and supporting local-national partnerships, using locally based staff to build understanding of local business sectors. If there is one thing (okay there are many things, but go with us) Oxfordshire is good at, it is innovation; a second would be spinouts. So which areas that Oxfordshire is known for are called out in the SDR as having potential to help scale the UK military?

Space

The space cluster in Harwell is highlighted in the SDR. Just as space technology has entered our daily lives through satellite TV, weather forecasts and sat-nav, so it has become embedded in military planning. The UK now has a 'Space Command' alongside other services. This has a role to protect satellite services which underpin about £1 billion a day of the UK's economy, a domain that the SDR calls “increasingly congested and contested”. It is also deploying its own space-based services for communication: ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance), and PNT (Positioning, Navigation and Timing).

It's a fast-moving field. Satellites that cost billions and were the size of a van, like the UK's £5bn Skynet 6 military communication satellite programme, are on the way out. Future systems will comprise larger numbers of smaller (washing-machine size), cheaper satellites like the ISTARI satellite programme (named after Middle Earth wizards). The Tyche imaging satellite (after the Greek goddess of fortune) became UK Space Command's first operational satellite last year. Another planned constellation, Azalea (a flower… clearly they're not all mythology fans), has even smaller satellites.

With Brexit, the UK dropped out of the EU's Galileo programme, losing access to the secure and jam-resistant versions of its navigation signal intended for emergency and defence services. This is a gap that still needs filling. As the SDR notes, the MoD needs to “ensure Defence requirements are reflected in cross-government efforts to deliver resilient space-based PNT systems”.

The UK's commercial sector puts it in a strong position for filling these gaps. UK-based companies have the ability to build complete satellites. Some of the companies are US or European owned, but the skills are resident in the UK. The one big gap is in launching the satellites, but after an initial troubled start we're likely to see UK-built launchers and launches from the UK (Scotland) this year... or maybe next. (Space is famously hard.) Oxfordshire's own spaceplane company is a story for another day.

We've already noted that Oxfordshire, and Harwell in particular, have a strong suit here. At Harwell Campus there are now over 100 organisations in the ‘space cluster’. Anchored by RAL Space, the national space research and technology laboratory, the Satellite Applications Catapult, which helps bring new ideas to commercial markets and the UK Space Agency, these range from branches of giants like Airbus and Lockheed Martin to smaller businesses like antenna manufacturer Oxford Space Systems and Earth observation data company Spottitt. Any of these may find opportunities in the new defence environment.

AI

The UK's first AI data centre will be in Culham, although it has not met with universal approval locally. AI has multiple military applications, from detecting and jamming radar to gathering intelligence and guiding drones. Though we might hope not to need these, if the horrifying conflict in Ukraine is a guide, this is the way that warfare is going. While the SDR sets out a 'NATO first' approach, in an increasingly unstable world, the UK must be self-sustaining in AI, making Culham a likely target. For investment, of course.

Quantum

Advances in quantum computing offer the potential to break commonly used encryption techniques, making secure communications and cyber security much more difficult. Quantum technologies also have the potential to reduce dependence on satellite-based GPS, which may be vulnerable to interference.

Last month, Oxford Quantum Circuits published a roadmap to dramatically improve quantum computing capability, which it claims is more than 10 times the highest level reached in published roadmaps for other quantum computing providers. Oxford Instruments, the original Oxford spinout (other than Cambridge University), recently sold its NanoScience Quantum Division. And again, last month, physicists at the University of Oxford set a new global benchmark for the accuracy of controlling a single quantum bit, achieving the lowest-ever error rate for a quantum logic operation. That's quite the hotspot for one county, even before you look at the National Quantum Computing Centre in Harwell (spotting a theme?) which was promised a decade of funding in the recent Modern Industrial Strategy.

Engineering biology

The SDR was never going to make the most restful bedtime reading, but we will single out this sentence as one of the most chilling.

Engineering biology that creates the potential to enhance the capacity of the armed forces through advances in medicine, healthcare, and wellbeing, possibilities for new energetic and explosive materials, as well as avenues for enormous harm in the shape of new pathogens and other weapons of mass destruction.

Once more, Oxford has known expertise in biochemistry, and medicine development, the most well known being the Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid vaccine. Last month, the OUP published a paper calling for a comprehensive reform of military medical planning of NATO and its allies based on lessons from the Ukraine War. The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine played no small part in the UK's pandemic response. Could the University, and the spinouts around it, contribute medical and biological science in the support of the UK military? Will the new labs being built in the city be a spearhead for emerging science in this vein?

Robotics and autonomy

With armed forces increasingly using uncrewed and autonomous capabilities, both for everyday tasks and for work that might be dangerous for humans to do (such as de-mining), Oxfordshire's expertise in robotics could come in to play. RACE is the UK Atomic Energy Authority's Centre for Remote Applications in Challenging Environments, and it's in Culham. OXA, in East Oxford, is developing self-driving software and autonomous capability using generative AI. Their test customers are Ocado and BP's wind and solar farms. But could it power autonomous uncrewed warfighting vehicles in the future?

Land

So far, so military. But all of this, must of course, be paid for.

The military estate takes up 1% of the land mass of the UK. One of the more innovative ideas to come out of the SDR was the suggestion of selling off some of that land, either for homes where security was not critical, or as lab/development space for dual use purposes. In other words, selling land close to (or even within) military establishments, particularly to civilian companies who are developing technology with application within the military. Could we see more labs built near Oxfordshire's six bases? Or land sold off that could ease Oxfordshire's housing crisis? Watch this space.

Conclusion

The SDR seeks to make the military responsible for developing regional clusters and supporting local-national partnerships, using locally based staff to build understanding of local business sectors. Based on the expertise already extant in the county, a cluster of military expertise in Oxfordshire seems likely.

In many ways the Oxford Cambridge Growth Corridor is doing this already, with Science Minister and Oxford–Cambridge Innovation Champion Lord Vallance setting out his vision to make the Corridor an economic growth engine for the entire of the UK. It remains to be seen whether the Oxford Cambridge Corridor and the Modern Industrial Strategy will dovetail with the Strategic Defence Review.

This all needs to be funded of course, and land sales as laid out above will not be the whole solution. But geopolitics does not stay still. The SDR says the Defence Investment Plan will be completed in Autumn 2025 – warp-speed for a project of this scale, and likely to make the Sir Humphreys quake. We could start seeing some of these changes as early as 2026.

We hope, of course, that we will never need to use the cutting edge skills of those in this county in a time of war. But it seems likely that growth in Oxfordshire will accelerate as a result of a change in military strategy, and just possibly, support this country in making Britain safer, secure at home, and strong abroad.

Further reading

- Strategic Defence Review

- Strategic Defence Review 2 pager: executive summary of the original

- You can see them from space – Oxford Space Systems: Clarion long read on a leading space innovator in the county.

- The Space Sector in Oxfordshire: an independent report on the themes and capabilities in the space and related sectors within the Oxford-Cambridge Arc

- National Space Strategy and National Space Strategy in Action, if you ever dreamed of being an astronaut.

- Defence Space Strategy which further explains the UK's approach to defence on the high frontier.

- National Space Security Policy (which gives deep context to every James Bond film in the last 20 years)

- The very model of a modern industrial strategy?: Clarion long read on the Government's Modern Industrial strategy, and its implications for Oxfordshire.

- Housing Week and Infrastructure Week: our series of long reads on Oxfordshire housing and infrastructure, because none of the above sits in a vacuum.