Sewage: The unsavoury blockage in Oxford’s planning pipeline

Health warning: we advise against reading this article while eating.

Oxfordshire has a sewage problem – one that is getting worse by the month.

Regular Clarion readers will know this, as will casual readers of almost any media outlet in the county; anyone who has received any political communication from any party recently; or any parent who has taken their little ones for a walk by a pond or river after rainfall. Sewage ends up in watercourses when Thames Water’s sewage system is at capacity. Without the ability to treat it, it discharges raw sewage into watercourses by the sewage treatment works.

Party poopers

There has been protest, after protest, after protest – from Banbury to Witney. Oxford had a Clean Rivers Festival featuring a singer dressed as a giant poo. Both Liberal Democrats and Labour made sewage a campaigning issue in the recent general election. Campaign groups from Windrush WASP to Henley Mermaids have kept up a steady drumbeat of noise about sewage in our watercourses.

🎥"The wildlife just looks sickly. We've seen swans with poo tide marks on their beautiful white feathers"🤢😡

— RiverActionUK (@RiverActionUK) April 3, 2024

Great work from @HenleyMermaids, keeping the spotlight on the Thames #sewagescandal and continually raising awareness on the plight of our rivers 👏👏 #RiverChampions pic.twitter.com/4t5PBsQ2TQ

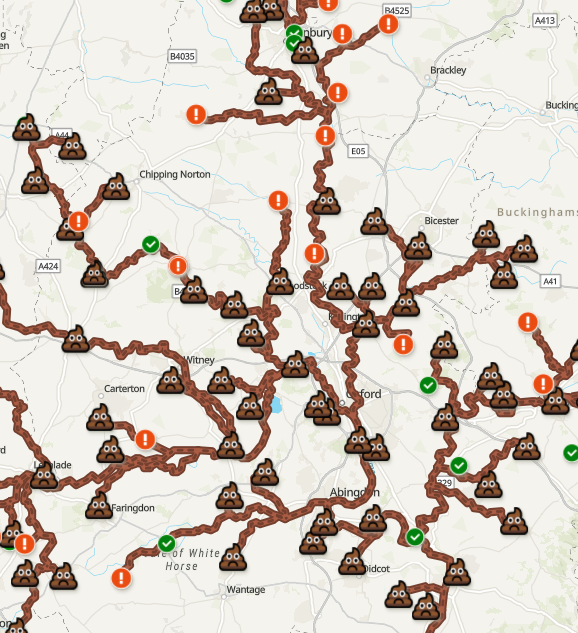

Alex Lipp at Merton College made a map that takes Thames Water data and maps it to a connected river network model to see which places downstream are affected.

The scale of the sewage dumping is illustrated by this graphic from Earthwatch which they catchily called ‘Top of the Plops’. For each sewage treatment works along the Evenlode, a Cotswold tributary of the Thames, it shows the total hours of raw sewage discharge. Congratulations to Milton-under-Wychwood for the most time spent issuing raw sewage into Oxfordshire's watercourses in 2024.

Flushing out the issue

Anyone who swims or paddles in our rivers, or has kids or dogs that do, will be only too aware why this is an issue. E-coli has been discovered in Hinksey Lake, Port Meadow, and the River Evenlode – three of Oxfordshire’s most beloved watercourses. Rowers are particularly at risk: Oxford University's rowing coach told newspapers the situation was a “national disgrace”.

But sewage in watercourses is dangerous in itself. It can kill some species, while its nutrient content can promote unnatural growth of others – algae, for example, which in turn affects the delicate riverine ecosystem and can kill off yet more species.

It may also create “sewage fungus”, according to a study from Oxford University. This is a complex mix of fungus, algae, and bacteria which forms large masses when there are high organic nutrient levels. They not only cause unpleasant smells, but severely reduce oxygen levels in water – adversely affecting all river species and causing mass fish mortality.

If that's not enough, sewage has been reported backing up into toilets around Witney and Radley. You should be able to rely on a flush toilet being a one-way device.

Up the creek without a paddle?

An explainer video taking a look into how sewage systems work.

Britain's sewage systems were once groundbreaking. Joseph Bazalgette designed London's sewer system, which helped wipe out cholera in the capital. (He also built bridges and roads and helped redesign London's streets to ease congestion from horse-drawn traffic. Plus ça change…)

Where London led, the rest of the country followed. Oxford was no exception: its sewer system was finished in 1880. (This excellent article by visiting Ukrainian professor Valerii Malko looks at the history of Oxford's sewers.)

But Oxford’s population has grown threefold since the 1880s, and continues to swell. Oxfordshire is set to add 100,000 houses over the next decade, with some 236,000 more residents to add to the current total of 738,000. The sewage system can’t cope with the current load. Are we all destined for mandatory Sunday 10am toilet flushing, as in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe?

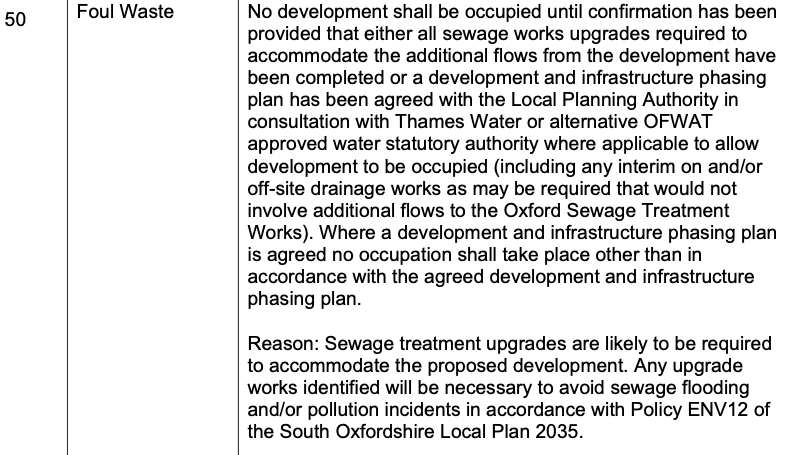

New homes are already running up against this capacity issue. In March 2024, the Environment Agency said it had “significant concerns about the performance of Oxford STW [Sewage Treatment Works]… we suspect it does not have any more capacity for new connections”, and that it understood Thames Water’s proposed improvements had been “significantly delayed” beyond 2025. The Christ Church-owned development beyond the ring road, which (in a rather Narniaesque tone) is known as the ‘Land North of Bayswater Brook’, has been given planning permission – but houses must not be occupied until sewage infrastructure has been upgraded.

This raises the very real possibility of the houses being complete before the sewage infrastructure works are completed with a possible, yet extremely vague ‘interim solution’, rumoured to be temporary holding tanks with sewage trucked away. Similar stipulations have been placed on Oxford University’s Begbroke South development between Yarnton and Kidlington, and the high-profile new Oxpens development in central Oxford.

Tim Bearder, county councillor for Wheatley including Land North of Bayswater Brook, commented to the Clarion:

“I'm deeply concerned that the district council approved this application despite serious objections from the Environment Agency. The conditions applied by the council allow the developer to deal with sewage on site until the Oxford Sewage Treatment Plant is upgraded, but no details were given on how that could be achieved, whether it will be safe or sustainable and who would monitor it. We could be in a position where we see hundreds of lorry movements carrying tankers of raw sewage across the county between Oxford and Upper Heyford, where we understand the developers own a treatment plant.

“The incredibly serious issue of sewage has been fudged, and we have no idea when or how it will be resolved. If this is how we are building houses now, I'm very fearful for South Oxfordshire when it is required to build 1,242 new homes each year – a development roughly the size of Land North of Bayswater Brook each year under the Government’s new targets.”

Oh CRAP (and the motions that followed)

Bearder is far from the only councillor up in arms on this. Politicians of all stripes are not happy.

Henley Town Council (independent-controlled) passed a vote of no confidence in Thames Water. Witney Town Council (Labour) did the same. South Oxfordshire District Council (LibDem/Green) called for Thames Water to be brought back under public control . Oxford City Council leader Susan Brown (Labour) said “they have let us and our environment down disgracefully”.

Oxford City Council agreed a City River Action Plan (that cannot have been accidental naming, surely?) after a city LibDem motion asking Government to place Thames Water into Special Administration, so that its £18bn debts don’t fall on the taxpayer. It issued a stinging statement on Thames Water:

“We have long been raising the major problems created by the historic lack of investment by Thames Water in the Oxford Sewage Treatment Works, and its subsequent lack of capacity. [...] This lack of investment has now led to the Environment Agency (EA) objecting to both the City Council’s proposed Local Plan 2040, and to housing and commercial planning applications coming forward in and around the city. This is a very significant environmental and economic issue for both Oxford and Oxfordshire. [...]

“We continue to press for an urgent resolution to build the infrastructure necessary to help clean up our rivers and support our local communities. Without this, there is a major risk that we negatively impact the Government’s agenda to deliver 1.5m new homes in the next five years, and to grow the UK economy, supported by Oxford’s world-class life science and technology sectors.”

All together now; Oxfordshire's politicians voting in Parliament on the Water (Special Measures) Bill in January 2025

Enema of the state?

Oxfordshire’s sewage is the responsibility of one organisation: Thames Water.

Thames Water is a private company providing, in many ways, a public service. It exists for the benefit of its shareholders: as such, its priority is profit. Thirty years ago, it was a debt-free public company.

Privatisation was intended to lead to a new era of investment, improved water quality and low bills. Instead, it turned water into a cash cow for investment firms and private equity companies, with correspondingly high shareholder dividends. As a data-driven Guardian article says, Thames Water’s modus operandi “was to borrow against its assets to increase dividend payments to shareholders”.

Thames Water now has the highest debt of all water companies. Population has grown across the south of England; capacity has manifestly not kept pace with demand; yet despite this under-investment, Thames has continued to return money to shareholders. As recently as December 2024, Ofwat – not known as the fiercest of regulators – banned Thames Water from issuing any further dividends until its credit score improved.

Freddie van Mierlo is MP for Henley & Thame, a constituency defined by the River Thames. He said:

“I am very worried that neither the Conservative or Labour governments have got to grips with our public utility companies. The failure of Thames Water to upgrade the Oxford Sewage Treatment Works is putting developers and the councils in an impossible position. It is holding back badly needed new homes and risking terrible environmental damage through leaks and discharges into our streams and rivers.”

Enter the Water (Special Measures) Bill. Introduced by the Labour government in September 2024, it had its second reading in January. The bill aims to address poor performance from water companies, whether financial management, water pollution, or outcomes for customers. The Government said it was introduced in response to a lack of public trust in the water industry. Are we making progress?

Witney MP Charlie Maynard has been a persistent thorn in the side of Thames Water, recently appearing at the High Court to argue against a bailout. We asked him if he thought the bill would bring the company under control.

“As someone who campaigned for cleaner, safer water in Oxfordshire long before becoming an MP, I was delighted to get the chance to scrutinise the Water Bill and put forward proposals to toughen it up. Along with my colleague Tim Farron, the LibDem environment spokesperson, I put forward 44 proposals to improve regulation of the water sector and better protect our natural environment. To give some examples, we called for water and sewage companies to have fixed targets to reduce pollution levels, to be made to monitor overflows on their network, and be made to publish data on the volume, length and number of sewage spills.

“It was regrettable that the proposals we put forward to the Water Bill weren’t accepted, and as a result it offers far weaker protections for our water than I would have liked. Nonetheless, I’ll keep pushing the Government to get tougher with water companies when it comes to cleaning up our rivers and holding them properly to account when they fail.”

No sh*t, Sherlock

The political waters are less murky than a year ago. Thames Water has agreed to a brace of STW upgrades, whether voluntarily or by force. The Water Bill will toughen up the regulatory framework, even if not fast enough for some. But is this fast enough for the rapid pace of development in Oxfordshire?

In November 2024, improvement works at the Benson Sewage Treatment Works were completed. In September we reported on the the upgrade of the Oxford STW being put out to tender. The works include tripling the size of the storm tanks, increasing treatment flow rate by 80%, and improving overall water quality. It is a £240m project, twice what Thames Water originally planned to spend on the project. But it will not be complete until 2031/32 – years after the first inhabitants are due to move into Bayswater Brook or Oxpens.

Planning applications have recently been lodged for upgrades at Henley-on-Thames, Sonning Common (near Henley), Milton-under-Wychwood (on the Evenlode), and Faringdon. Cholsey, Witney and Charlbury and more are also earmarked for expansion. Thames Water say the works will help these smaller sites to “meet all government targets for storm overflows” between 2026 and 2030. (You can check out the progress on your local STW here.)

Is this simply running to stand still? Planning applications have been moving forward at pace for the Land North of Bayswater Brook, Upper Heyford, Culham, Salt Cross and many, many more. Is anyone joining the dots on the sewage capacity the county will need in the future?

Witney MP Charlie Maynard again:

“The planned increase in homes in Oxfordshire must be matched with investment in our water and sewage network. We need changes to the planning process which mean the impact on the capacity of the local sewage system is always considered when approving new developments. One of the amendments I argued for in the Water Bill was that water and sewage companies should be included in planning consultations and be required to provide full and honest information to them.”

In late January, the Government announced a Growth Commission led by Lord Vallance. The Oxford–Cambridge Arc has been rechristened a “growth corridor”, a local powerhouse of innovation:

“Oxford and Cambridge offer huge potential for our nation’s growth prospects. We are not prepared to miss out on the opportunities here any longer. We are going further and faster to unlock the potential of the Oxford-Cambridge Growth Corridor.”

This was the promise of Rachel Reeves, Chancellor of the Exchequer, delivered in a speech in Eynsham. She blamed Britain’s slow growth on “our planning system”, “decades-old green belt policies”, “the lack of a proper industrial strategy”, and “a £100m bat tunnel for HS2”. Sewage was not mentioned once.

Yet sewage, not a bat tunnel, is the immediate threat to development in Oxford. There are three city developments where builders are ready to move in, yet where no houses can be occupied until the sewage situation is fixed. The people powering this brave new growth engine of the UK all need to live somewhere. Government cannot wash its hands of the problem for much longer. Otherwise, we will all need to wash our hands rather more often.

This is part of the Oxford Clarion’s Infrastructure Week series. Read our introduction to the series – and why we should all care.