The life and death of Oxford’s ‘effective altruism’ dream

The ripples from the conviction of Sam Bankman-Fried, the fraudster whose FTX crypto empire collapsed into bankruptcy from a valuation of $32bn, continue to make waves a long way from the Bahamas HQ of the one-time wunderkind.

Wytham Abbey, a 15th century manor house just outside Oxford, has gone up for sale for £15m. The building was owned by an Oxford-based charity, funded by ‘SBF’ among others, which promoted effective altruism – the notion that the best way to change the world was not to become a doctor, or an aid worker, but a seriously rich banker who could fund more doctors and aid workers.

After the SBF connection led the Charity Commission to institute an investigation, the charity, Effective Ventures, announced its closure. Its Wytham Abbey Project is one of the first to be wound down.

But what exactly is effective altruism? How did Oxford become the global headquarters of a billionaire-backed movement to change the world? And why has it all come crashing down?

“Something of an intellectual scam”

The premise behind effective altruism is simple. The best way to change the world is to become filthy rich, and then direct those dollars to rigorously researched spending on improving the human condition.

Think of Bill Gates’ philanthropic works. Now imagine if Gates, in 1975, had sat down and said “I’m going to dominate the personal computer market solely as a means to the end of eliminating malaria”. Imagine that Windows, Office and Internet Explorer were intentionally developed as the products that would bring the biggest return to be spent on good works.

Then think back to the anti-trust battles of the late 90s, where Microsoft was convicted of misusing its monopoly to drive out competitors such as Netscape. Such behaviour, in the world of effective altruism, can be justified if it earns more money to be spent on good works. In the words of Clive Crook (ex-FT/Economist):

You judge acts by comparing their effects on the global sum of happiness, and the morally right course is the one you expect to achieve the maximum effect. Crucially, other moral considerations – obligations to be honest, to be just, to be loyal, to respect property rights and many more – count only to the extent that they bear on the happiness calculation.

It’s an intensely seductive vision, particularly to the intellectual courtiers of the Silicon Valley elite whose billions genuinely could change the world. Philosophy lecturers don’t often get invited to soirées at California beach mansions.

It’s also an intensely comfortable vision. Moving in such circles requires living like a lord. But you can justify that as an expense if it results in more money for your altruistic goals. Would SBF’s spiel have won over investors if it were delivered from a Berkeley basement, not a Bahamas penthouse? Would the Effective Ventures Foundation raise more money from tech leaders over coffee in an Oxford office block – or if it could wine and dine them at Wytham Abbey? As the New Yorker put it:

The Centre for Effective Altruism bought Wytham Abbey, a palatial estate near Oxford. Money, which no longer seemed an object, was increasingly being reinvested in the community itself. The math could work out: it was a canny investment to spend thousands of dollars to recruit the next Sam Bankman-Fried.

But the logic of the exponential downstream had some kinship with a multilevel-marketing ploy.

Why Oxford?

There is nothing new in gurus appealing to the super-rich with a promise of changing the world. Sixty years ago, the Maharishi won over the Beatles with a promise of world peace. (He died in 2008, leaving an organisation whose holdings were valued up to $5bn.)

Yet the cold, calculating premise of effective altruism, and the gilded circles in which it was advanced, seem a long way from the corridors of Oxford academia. How did Oxford become the intellectual centre of this global movement?

The answer begins with its own guru, William MacAskill.

EA’s Oxford antecedents go back centuries. Jeremy Bentham, the high priest of 19th century utilitarianism, had his eureka moment in Queen’s Lane Coffee House. For Peter Singer, the Australian philosopher of “applied ethics”, a lunch at Balliol set his convictions. All Souls’ Derek Parfit was Oxford through and through. But it was MacAskill who forged what we today call effective altruism.

Born in 1987, William MacAskill is the Millennial boy wonder among the GenXers who dominate this branch of philosophy. (One early critique called effective altruism “a rather homogenous movement of middle-class white men fighting poverty through largely conventional means”.)

He hatched his theory of effective altruism during his graduate studies at Oxford, developing ideas over long talks with research fellow Toby Ord. A 2011 talk, ‘Doctor, NGO Worker, or Something Else Entirely?’, set out his emerging philosophy. The slides, published under his pre-marriage name of William Crouch, are still online. It sets out a simple fable:

Suppose that Jo becomes a doctor working in the developing world. She performs 10 life-saving surgeries every week.

Suppose that Lorna becomes an altruistic banker, earns £400k/yr, and donates enough money that she pays for 10 developing-world doctors. That means 100 lives per week would be saved.

The banker was able to save ten times as many lives as the doctor, even though she wasn’t directly saving any lives in her career. The moral: Ways of indirectly benefiting others, such as earning big and donating, can do much more good than directly benefiting.

But it moves swiftly on to the “comfortable” component of effective altruism:

Successive slides went on to co-opt Bill Gates and, shamelessly, Oskar Schindler as proto-effective altruists. All this, it implied, was within the audience’s reach: “Almost any Oxford graduate can make a lot of money.”

By slide 47 it has shaded over into multi-level marketing territory:

Consider, for example, the canny persuader. She decides not to make money, but instead to persuade others to make money to give it away. In one year, she persuades 10 Oxford students to become professional donors.

Still, it’s a philosophy almost tailor-made to attract Oxford graduate disciples. Change the world, be widely admired, and still enjoy a “high-flying lifestyle”. Who could resist?

This new philosophy found kindred spirits in Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute. (For plot development reasons we’re not hyperlinking it quite yet.) Nick Bostrom, who founded the Institute in 2005, was not (and is not) chiefly an effective altruist. His main area of research is human extinction, and how to prevent it – the notion of man-made “existential risk” from developments such as artificial intelligence.

But the FHI provided a nurturing cradle for MacAskill’s emerging creed. Its core approach was essentially the same: a philosophical, technology-informed take on the survival of humanity. MacAskill’s co-conspirator Toby Ord was a research fellow there. If effective altruism dealt with raising money, FHI debated how best to spend it.

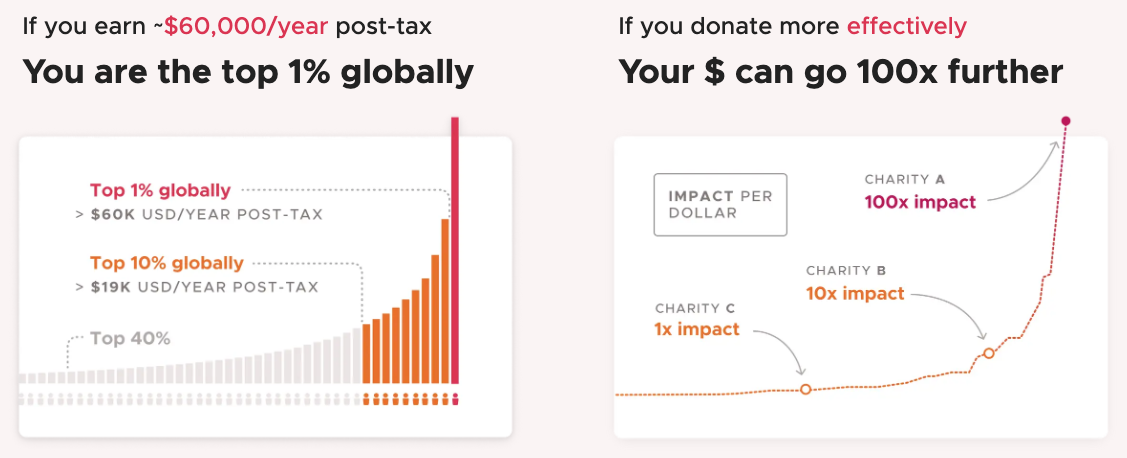

MacAskill and Ord founded the Centre for Effective Altruism in 2012. It shared premises with FHI in the university-owned Trajan House, on Mill Street in Osney – a hothouse for futurist thinking and utopian research. Growth was rapid and followed a predictable playbook: conferences, spin-off foundations, an “online fellowship” e-learning course, self-help careers guides, and an expensive new headquarters/events space (Wytham Abbey). One of its best-known projects, Giving What We Can, is effectively MacAskill’s 2011 slide deck in corporate form and with better typography:

Sam Bankman-Fried came on board for a while, briefly serving as the Centre of Effective Altruism’s director of development before leaving to found Alameda Research, the trading firm that would ultimately take down FTX. Elon Musk spoke at CEA-organised conferences. In 2022, CEA became ‘Effective Ventures’, the name change reflecting the circles in which William MacAskill’s acolytes now moved: venture capitalism for good.

The Centre for Effective Altruism was not a University project. But the academic underpinnings of MacAskill’s philosophy remained strong. The Faculty of Philosophy, perhaps sensing that it was missing a trick, founded its own effective altruism centre, the Global Priorities Institute (“our aim is to conduct foundational research that informs the decision-making of individuals and institutions seeking to do as much good as possible”). It, too, was headquartered in Trajan House. Its founding director, Hilary Greaves, continues to co-author papers with William MacAskill with titles like ‘On the desire to make a difference’ and ‘The case for strong longtermism’.

Oxford-trained effective altruists reached out across the world. Carrick Flynn was the first US politician to openly advocate effective altruism, after a grounding in Oxford in the mid-2010s. Sam Bankman-Fried bankrolled Flynn’s 2022 run for Congress, which majored on the pandemic preparedness message he had studied in Oxford. He lost the Democrat nomination – handsomely – to Andrea Salinas. Unbowed, Flynn returned to Oxford where he became an affiliate of the Centre for the Governance of AI, another Effective Ventures project. (The Centre told us that “GovAI’s affiliates are a global network of researchers that the organisation may choose to collaborate with on an ad-hoc basis, but they play no role in our running or operations.”)

For all Oxford’s influence, effective altruism was still charity seen through a California-futurist ‘tech bro’ lens. Fund artificial intelligence for a better world. (Kickback: your tech company gets more work.) Fund cryonics and eliminate death. (Kickback: you’ll be one of the first to live forever.) Lobby for EA causes to get tax-deductible donations. (Kickback: you, not those pesky governments, get to decide how to spend your billions.) If this is indeed social progress, it’s one very particular take on it. Not many effective altruists are Marxists.

What went wrong?

Sam Bankman-Fried went wrong.

William MacAskill had been quick to notice SBF. He recruited him to the cause in 2012, seven years before FTX was founded. By 2014, SBF was giving half his New York trader’s salary away: some directly to charity, some to EA causes. Three years later, he was working for MacAskill’s Centre for Effective Altruism. In FTX’s pomp, he spoke of donating $1bn a year.

Unfortunately, as SBF’s trial laid out over the course of October 2023, that billion wasn’t his to donate. FTX had played fast and loose with customer funds. Much went to prop up trading losses. Some was spent on expensive sponsorships, political donations and executive comfort. $27m went to CEA/Effective Ventures. How much actually reached genuine, non-speculative charitable causes is lost in the FTX accounts… if indeed it ever was documented there.

Effective Ventures was forced to pay back FTX’s $27m. But this in itself wouldn’t have spelt financial doom for the project, which had income of £140m in 2022. Rather, it rapidly became apparent that SBF’s conviction had severely dented investor confidence in effective altruism – and without the support of those Silicon Valley moguls it had courted so assiduously, Effective Ventures could no longer function.

Wytham Abbey, intended for lucrative conferences, was the first casualty. A statement read:

While the project cleared the donors’ funding bar at the time of the original grant, and by all indications the project was well-run, a subsequent drop in the level of funds available to support the community working to reduce global catastrophic risks caused the Abbey’s donors to revisit the project.

Another announcement explained, true to the principles of effective altruism, that “The proceeds of the sale, after the cost of sale is covered, will be allocated to high-impact charities.” Hilariously, Effective Ventures CEO Rob Gledhill later footnoted this with “Since this announcement, we have decided that we will use some of the proceeds on Effective Venture's [sic] general costs. I consider EV to be a high-impact charity.”

This was a clue that the “drop in the level of funds available” affected more than Wytham Abbey. With an SBF-inspired Charity Commission investigation hanging over it, Effective Ventures “decided that the charitable purposes for which the charity was set up would best be served by spinning out all of the projects into new independent entities” – in other words, closing down EV itself. (The Charity Commission duly found that EV’s finances had been a “weak point” and that conflicts of interest with FTX had not been monitored.)

Nick Bostrom’s Future of Humanity Institute was the next to fall. It said “increasing administrative headwinds within the Faculty of Philosophy” had cramped its work from 2020 – around the time when effective altruism was enjoying its moment in the sun. The Institute was closed on 16 April 2024. In a self-penned eulogy, it saluted its work on effective altruism:

There was substantial cross-pollination between the ideas and methods of effective altruism and FHI. Effective altruism was influenced by many FHI ideas, including macrostrategy, existential risk, and taking humanity’s position in the universe seriously. Effective altruism in turn influenced FHI’s approach to choosing research topics — selecting for those where we could make the greatest counterfactual impact.

Those outside the Institute were less kind. A Guardian report said FHI had inspired “a cult-like following, which may have alienated many in the wider philosophy community in Oxford and indeed among the university’s administrators”. Bostrom was linked with eugenics and a 1990s email that declared “Blacks are more stupid than whites. I like that sentence and think it is true.” One critic called this “the last straw for the Oxford philosophy department”.

Only in Oxford?

Maybe only Oxford could have invented effective altruism. The university’s most famous, perhaps notorious, course is Philosophy, Politics & Economics: PPE. The list of UK politicians with Oxford PPE degrees is long. It includes Rishi Sunak, Liz Truss, David Cameron, Rory Stewart, Ed Davey and both Milibands. In political commentary, PPE has almost become a sneer, applied to those who might understand the theory of governing but none of its real-world human impact.

Indeed, William MacAskill’s 2011 slide deck unwittingly echoed the stereotype of the entitled PPE student:

Is effective altruism merely PPE for the 21st century? Was Wytham Abbey the ivory tower of a new movement, turning out disciples who want to change the world without getting to know it first?

In effective altruism, everything has its price. Wytham Abbey’s price is £15m.