You can see them from space: Oxford Space Systems

Later this year, a rocket will blast off from Florida carrying a satellite made by Surrey Satellite Technology Limited (SSTL).

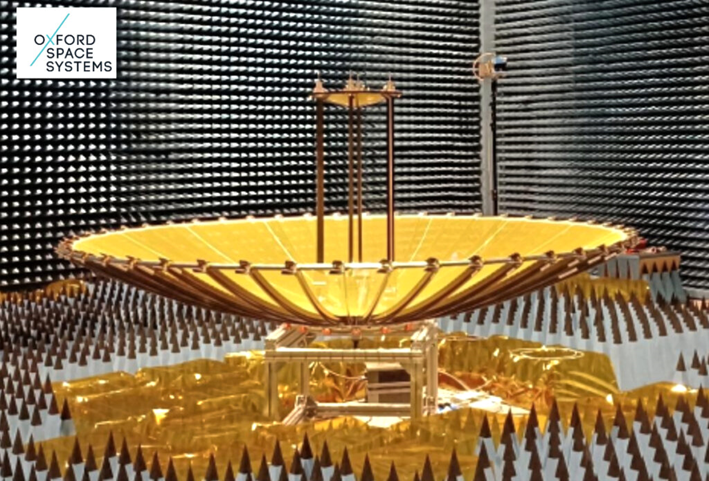

It’s a demonstration radar satellite, and on board, making an ambitious mission possible with a satellite the size of washing-machine, is the radar dish – or more accurately, the antenna – made right here in Oxfordshire. At launch it is folded up into a thin doughnut, 75cm across; but once in orbit, it unfurls to a golden dish bigger than you or me, a full 3m across. This is a product of Oxford Space Systems, part of the growing ‘space cluster’ at Harwell Campus in the south of Oxfordshire.

The origin story

After its role as an airfield in World War 2, Harwell became the Atomic Energy Research Establishment – its isolation, fences and abundance of open flat land providing the ideal location for facilities and expansion. In 1957, it was joined by the Rutherford High Energy Laboratory (now the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, RAL), which developed space research including instruments for NASA and ESA probes.

The early 2010s saw the emergence of space as a significant UK industry. In 2010, the UK Space Agency was formed. In 2013, the European Space Agency (ESA) and Satellite Applications Catapult arrived at Harwell. Despite the name, the latter is (unfortunately) not a giant piece of elastic to launch satellites, but an organisation that assists innovation and business growth in the space sector. Oxford Space Systems was one of its earliest proteges, also formed in 2013.

Your Clarion correspondent has followed their progress for several years, so we were delighted when we got the invitation to meet with Juan and Zoe from OSS. This was our first chance to look inside their dedicated building since they moved out from under the Catapult’s wings in 2018. We meet in the ‘Alderaan’ meeting room. Despite the omens, we have a good feeling about this.

The clean room is the largest on Harwell campus with a several antennas in construction and testing. It’s maybe half the size of a school sports hall, but much cleaner, and I only get to look through the windows as gowned and hair-netted technicians go about their business.

Small packages

The key to success in the space business is to get your products ‘space proven’. For OSS, that moment came in the form of OSS’s big breakthrough with the deployment of their Astrotube™ Boom from AlSat-1N in 2016. This was a small UK-Algerian satellite launched on an Indian rocket. The boom unfolded from a 10cm package to extend 1.5m, a bit like a tape measure does, but more rigidly. It was a great success, but Juan is keen not to focus on the moment. “It’s not the breakthrough, more it’s what you do every day that adds up. Yes, this was a milestone, and an important milestone, but the journey to get there is a cumulative effort.”

Since then the effort has continued, and OSS has grown from a few tens of people to 100. In addition to the ‘boom’ its main line of products are deployable antennas, for sending radio signals in various shapes and sizes. This is crucial, because while rocket launches have got cheaper, the space inside the rocket’s fairing is still very expensive, and the antenna can be one of the biggest parts of a satellite. Being able to launch small and unfold big is a great advantage.

Take a look at the OSS website, and you will find delightful animations of cylindrical ‘helical’ and ‘yagi’ antennas popping out of satellites. These are proving popular – on one SpaceX launch in January, satellites for three companies carried different OSS antennas.

From doughnuts to ribs

Success in these smaller antennas gives OSS the resource to move on to the bigger dish we described at the start: the ‘wrapped rib’, which looks like a golden and much scaled up version of a satellite TV dish. The ‘ribs’ here are what provide the final shape, and also the spring tension to unfold from the original ‘doughnut’. These ribs have been designed to be flexible, while taking advantage of carbon fibre’s lightweight and stiff properties. As we tour the site, we can also recognise the benefits to local shops and services of having 100 super hi-tech employees in the south of the county.

The surface is a fine gold-plated mesh. It is knitted from gold-plated metal thread one-tenth the thickness of human hair (which sadly is not available in Mason’s of Abingdon) by a conventional, if somewhat tweaked, industrial knitting machine. Rumpelstiltskin had nothing on this! We have to walk gently up the stairs, just in case knitting is underway.

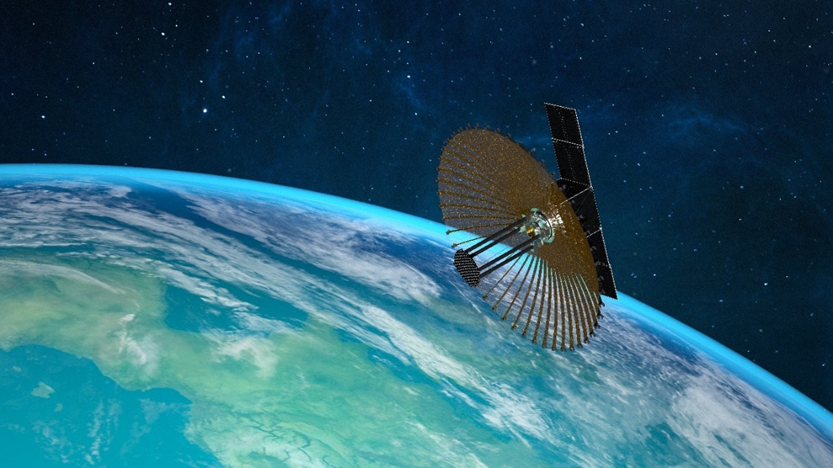

The dish will sit on one end of the ‘CarbSAR’, a 140kg satellite made by Surrey Satellite Technology Limited. Once a spin-out from the University of Surrey, SSTL is now owned by aerospace giant Airbus. CarbSAR is a Synthetic Aperture Radar satellite, which scans the surface of the Earth with radar beams and uses the movement of the satellite and lots of computing power to simulate (this is the synthetic bit) a larger aperture or dish. If you are wondering why a dish is named an aperture, which is a hole, that’s because telescopes for light came before telescopes for radio, and they started as tubes with lenses in. The size of the hole or aperture was important – and it still is. (The Carb bit is because it is based on SSTL’s Carbonite series of satellites. Some of you may recall Han Solo being frozen in Carbonite in the Empire Strikes Back – it seems that SSTL are Star Wars fans as well.)

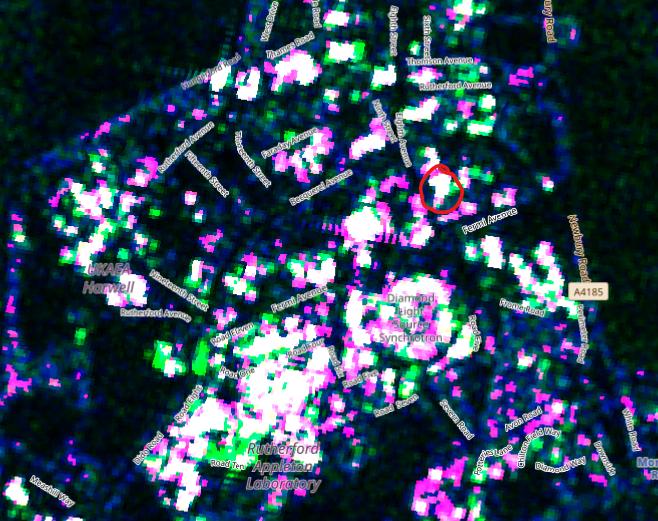

SAR has the benefits of seeing at night, or through clouds, and CarbSAR has the ability to resolve objects 50cm across, easily enough to spot the building we are in. Previously, satellites like this used to be large and expensive, so might only revisit a location every week, but with new technologies like the wrapped rib antenna making them smaller, they can be launched by the dozen in a ‘constellation’, allowing daily scans. Very useful for environmental monitoring or disaster response or defence.

The satellite future

Meanwhile, sales of smaller antennas are going well. A sure sign of a good product is that they are winning export orders, and they are winning orders for groups of satellites as well, allowing production to scale up.

From defence, to navigating our journeys, to monitoring pollution, as satellites become cheaper to make and launch they are quietly entering more aspects of our lives. They remain complex, and there are many businesses creating and assembling their components.

Walking away from OSS, we’re struck by the cranes and construction – there seems always to be another building going up at Harwell. It’s a sign that, like Oxford Space Systems, the campus and its space cluster are Oxfordshire success stories.