Make Oxford Great(er) Again

Occasionally your Clarion team just stops and stares in admiration at the sheer political chutzpah of our city and county’s politicians.

The ‘Greater Oxford’ proposals unveiled today by Oxford City Council are one such example. Politically, they’re one of the shrewdest moves we’ve seen. Malcolm Tucker would be envious.

A quick recap before we dive in. The Government wants to replace ‘two-tier’ councils (county does some things, city/districts do others) with ‘unitary’ councils where one council does everything. (Here’s our primer.) Local councils have been asked to draw up plans for these new authorities. Unsurprisingly, instead of digging their own graves, they have mostly responded with proposals to embiggen themselves while abolishing the others.

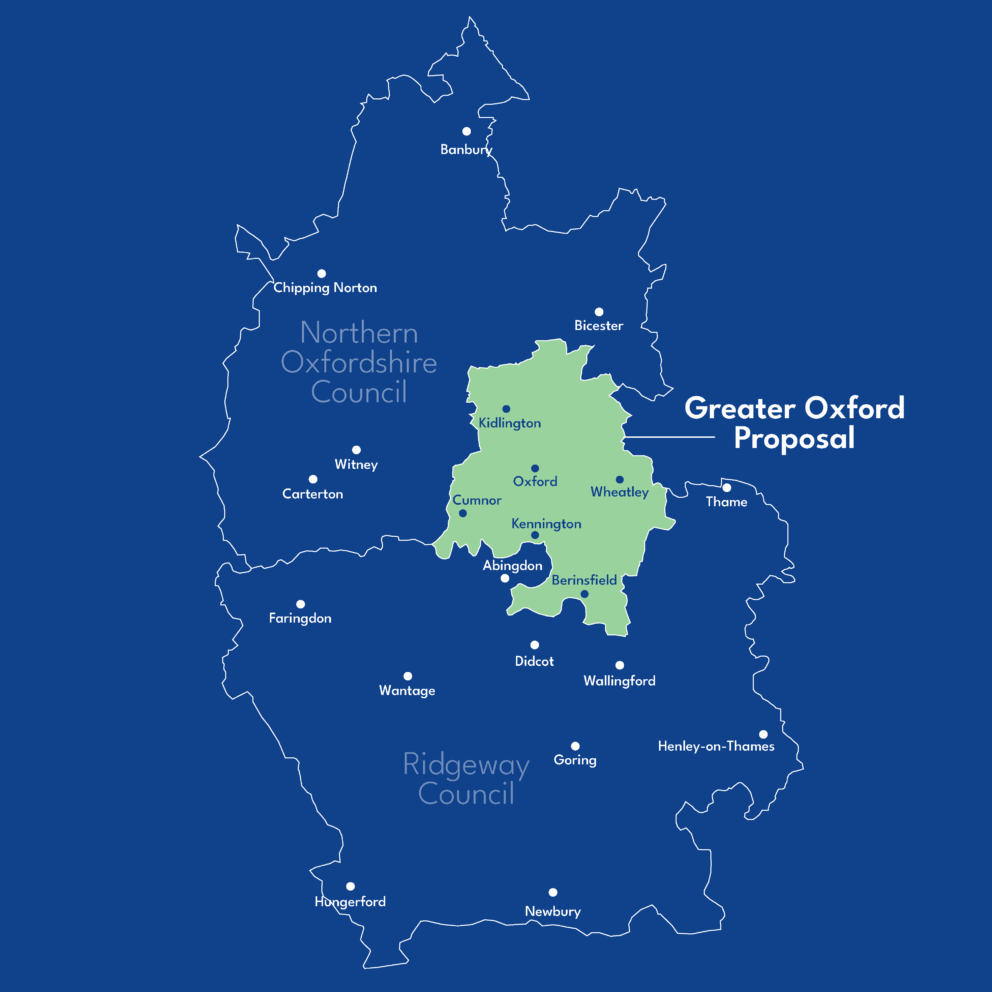

In Oxfordshire, that means the County Council proposes a whole-Oxfordshire unitary, abolishing the city and districts. The rural districts want to merge with their neighbours to create two new unitaries. And the City Council wants a “Greater Oxford”, an expansionist city on larger boundaries, with two remainder authorities left to fight over the scraps. (More details from March.)

From day 1, the Greater Oxford plan seemed the least plausible of the three. That’s partly down to numbers: the Government wants unitary councils to have at least 500,000 residents, and dividing Oxfordshire’s 750,000 residents into three councils gets you half of that.

But it’s also a question of definition. What is Greater Oxford? So far the best response has been “anywhere Inspector Morse investigated a murder”. Oxford City Council thinks it has a better answer.

Redrawing the map

Here’s what the City Council proposes for its new “Greater Oxford” council.

It’s an expansionist view of Oxford, incorporating its dormitory villages but, crucially, not its satellite towns. Abingdon, Eynsham, and Woodstock are out. Kidlington and Kennington, Begbroke and Berinsfield, Wheatley and Botley are in. Intriguingly, so are Culham and Clifton Hampden.

Here’s the political calculation, part 1. The rural districts would scream if it were any bigger. Vale of White Horse would march on Westminster at the prospect of losing Abingdon. West Oxfordshire would riot for Eynsham. That’s been avoided. Ok, Cherwell might be a bit miffed to lose Kidlington. But this is a proposal that the districts could, begrudgingly, accept. South and Vale still get their prize of a new ‘Ridgeway Council’, while the northern districts have barely suffered a flesh wound.

Here’s the political calculation, part 2. A phrase heard in the Clarion WhatsApp today was “it’s very Labour”. This is a package of Oxford expansionism, parcelled up in a Labour-controlled council, ready to deliver to a Labour government which has already signalled its enthusiasm for expanding Oxford. No pesky LibDem NIMBYs to fret about the Green Belt: Labour shall speak development unto Labour. The argument to Government is: “It’s not 500,000 residents… yet. Can we interest you in a new town in Culham?”

Here’s the political calculation, part 3. Look how the votes fall. A single Oxfordshire unitary would vote LibDem. A two-council setup would do the same. Only with a “Greater Oxford” council does Labour have a chance of retaining any political control. But not too much greater, or the LibDem votes from Abingdon and Eynsham might pose a threat.

You can see why we think it’s clever. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s any good.

The shape of things

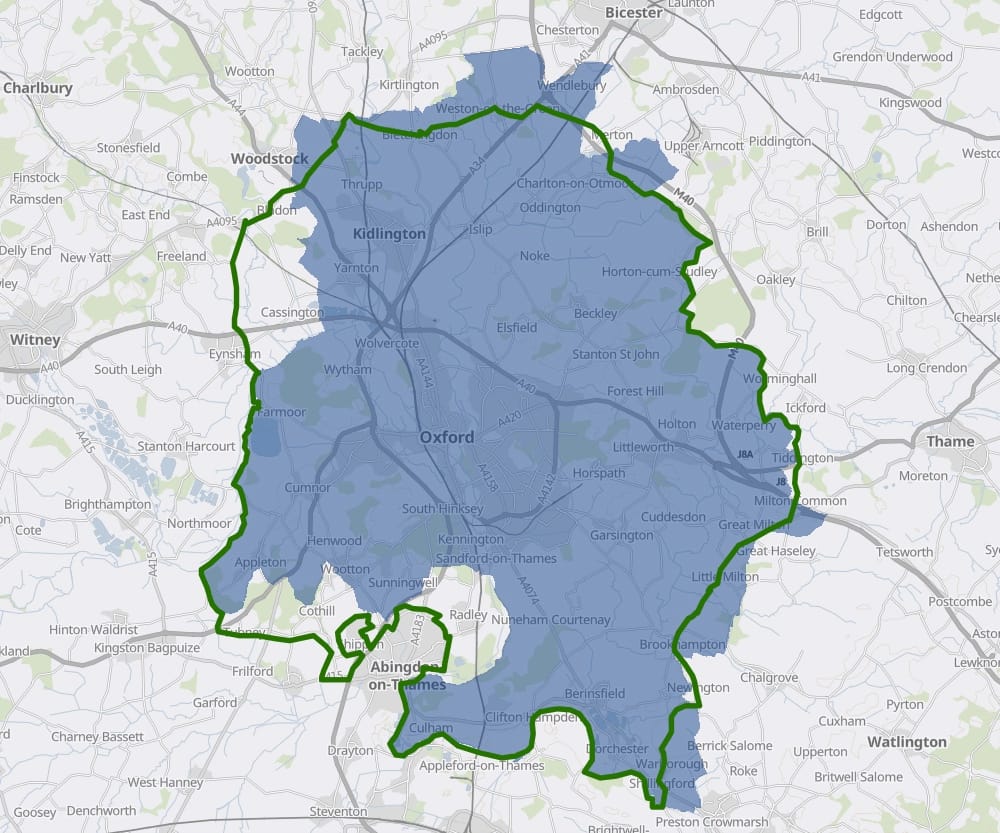

Squint at the map and it looks remarkably similar to another map you might remember. It turns out that Greater Oxford is, pretty much, the Oxford Green Belt.

We wrote about the Green Belt in our Housing Week series. It is under threat. For many people, let’s be clear, this is a good thing. A 1958 blueprint is still constraining housing supply in Oxford, 67 years later. The Labour government’s planning rules have relaxed this by introducing the notion of “grey belt”, less valuable Green Belt land with fewer development protections. We’re already seeing encroachment on the Oxford Green Belt with developers arguing it’s grey belt land.

So to get from a population of 240,000 today, closer to the Government’s magic 500,000 figure, the new Greater Oxford Council would build in the Oxford Green Belt.

No one is going to build a new town on Port Meadow, Otmoor, Shotover Hill or Waterperry; alongside the new Flood Relief Channel in West Oxford; or in the environmentally sensitive floodplains of the Cherwell and Ray. (Play with the layers at DEFRA’s Magic Map to see where is out of bounds.)

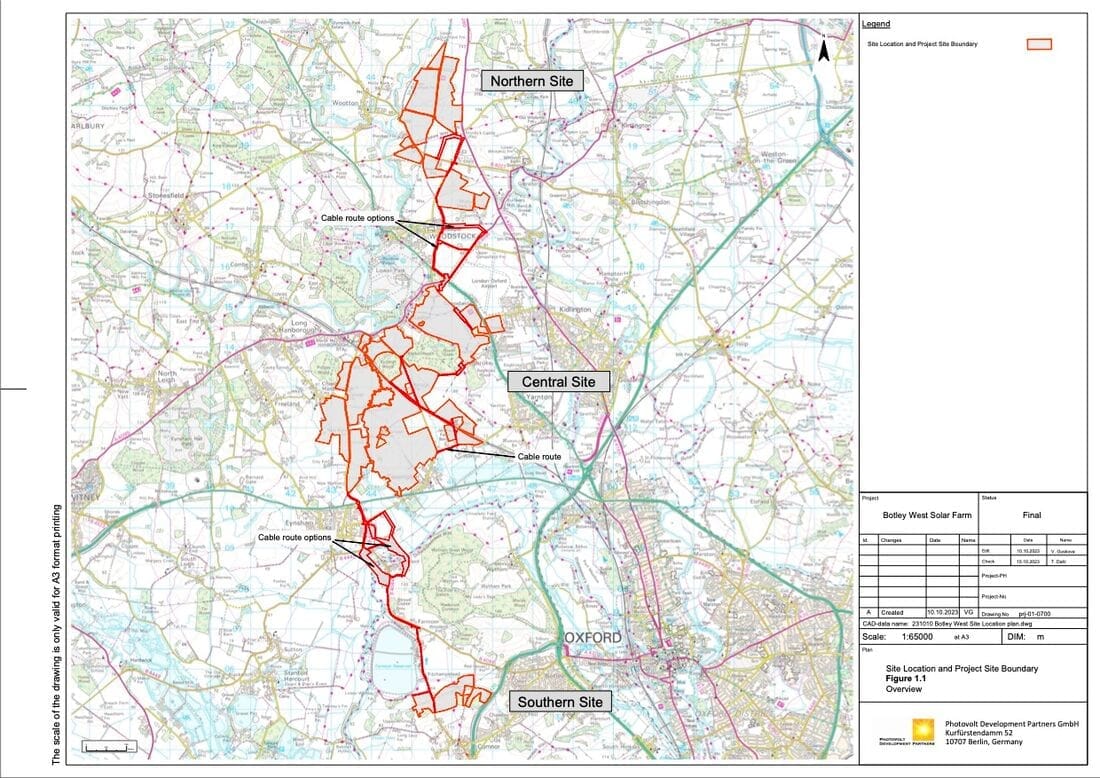

That leaves a small number of plausible places to build Greater Oxford’s first new 100,000 houses (the plan officially targets 345,000 by 2040). Culham, which we wrote about last year. Begbroke, Yarnton and Kidlington. Wheatley and Horspath. Berinsfield. Islip’s northern edge. Expect the boundaries of “city Oxford” to grow, to the south-east and perhaps beyond Cutteslowe, and look for grey belt development alongside major roads.

No one departs, no one arrives

That leads us to the Achilles heel of this proposal: transport.

Culham and Islip have (small) railway stations. Begbroke could get one. But there’s no railway anywhere near Wheatley, Cuddesdon, or the eastern A40. Development there would be entirely dependent on private cars or buses, and Oxford has run out of capacity for both. Any resident of Wheatley New Town would be catching the same bus to work that sits in traffic on St Clements every day.

If Greater Oxford’s 100,000 new residents are to get to work quickly, easily and affordably, they will need either an expensive silver bullet like a tram system, or for Oxford’s bus-friendly traffic filters to be cranked up to a full-on Ghent rather than the watered-down replica currently proposed. Since Labour’s county councillors have recanted their support even for the weakened filters, we have our doubts about this.

The plans have little detail on transport, saying merely that “The proposals would provide additional bus services to villages around the city by extending existing routes.” But to take one example, Stadhampton’s public transport problem isn’t frequency, it’s that the morning commuter bus takes 46 minutes to Oxford city centre – an average of 9.9mph. Additional services won’t help if those services end up queuing for the Plain.

A proposal could be made for a railway-centric Greater Oxford. But this isn’t it. (Maybe we should write one.)

A speculative side-note: the proposed boundaries of Greater Oxford face towards the Oxford–Cambridge Arc Growth Corridor, along the A34 and A40 corridors. Should the Government ever resurrect the Oxford–Cambridge Expressway, its proposed route between the A34 and M40 would largely run through Greater Oxford territory. How do you make the traffic filters more Ghent-like? Free up space on the ring road by diverting long-distance traffic round the south. Tempting for a council largely elected on votes from city, not country. We didn’t say any of this.

Our one source of energy

Oxford needs homes, and those homes need infrastructure: electricity, water, sewage. (We wrote about this in our Infrastructure Week series.)

Greater Oxford will not be self-sufficient. Botley West Solar Farm falls almost entirely outside its boundaries. Abingdon Reservoir will be a headache for Ridgeway Council, not Greater Oxford.

That’s not necessarily a problem. No one expects that Rutland Water will only supply water to the residents of England’s smallest county. But it sets up planning battles for the future. Rural district councils may be less keen to sign over farmland to solar power if all that capacity is being used up by Oxford City. A council that includes both city and country can balance these demands: an urban unitary can’t.

On the upside, Oxford United’s proposed new stadium at the Kidlington Triangle would be within the Greater Oxford bounds. The planning decision should be taken long before any new council comes into effect, but with city councillors having enthusiastically endorsed the project, this would be a fillip for OUFC supporters.

Oxoniensis est omnis divisa in partes tres

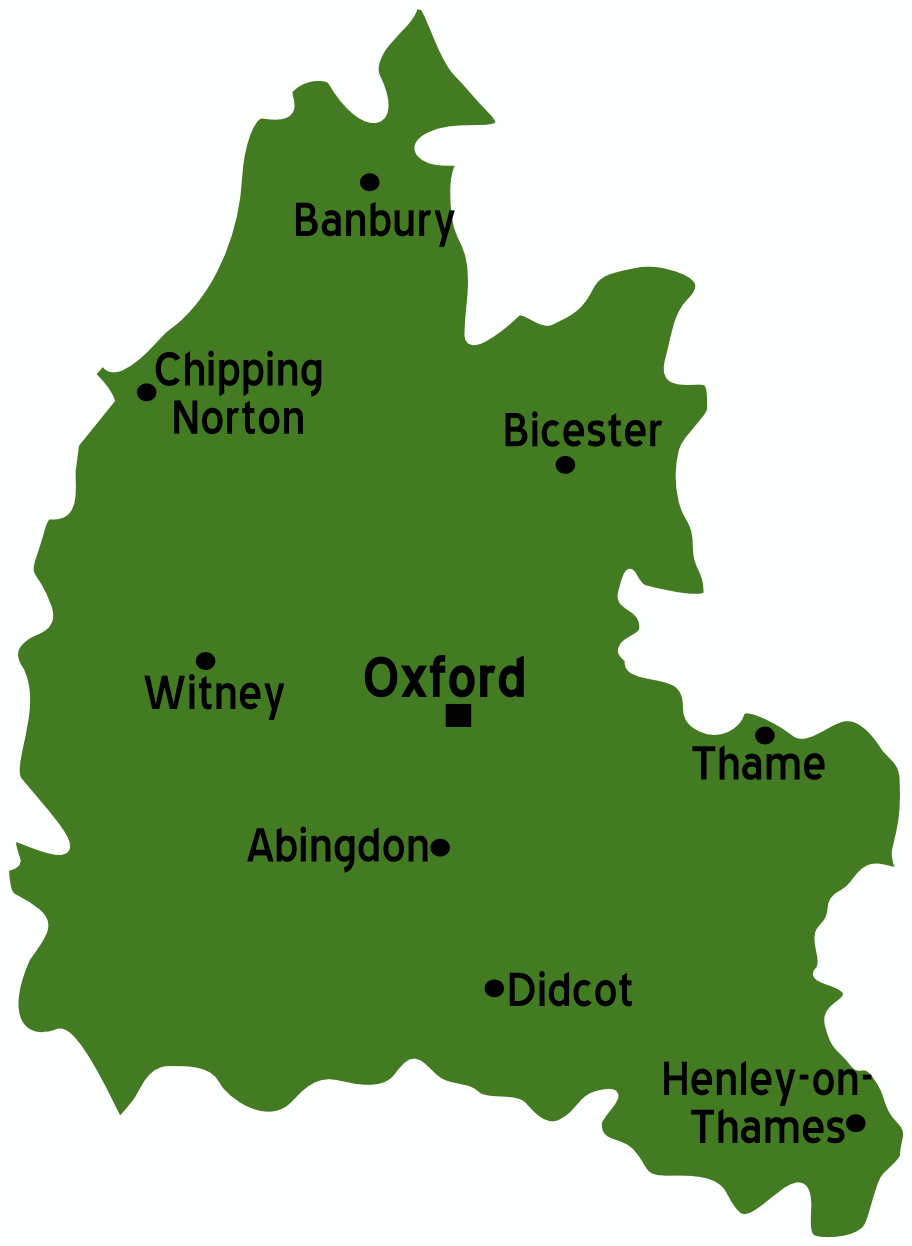

Any proposal to divide Oxfordshire into multiple councils has to answer the question: “Why not just Oxfordshire?”

Because there is arguably already a Greater Oxford, and it looks like this:

The economies of Witney, Abingdon and Didcot are intimately tied up with Oxford. Small settlements like Eynsham, Woodstock and Charlbury are wholly dependent on the city. A Greater Oxford Council would exclude all of these. Divorce Witney from Oxford, and there’s no one pushing to improve the A40. Cut off Didcot, and the voice for Didcot–Oxford railway electrification is diminished. And so on.

The Greater Oxford website sums up its answer to the question like this: “Our proposal would bring local decisions under one roof and closer to the people they affect.” But it would be more accurate to say “some of the people they affect”. What happens in Oxford affects the rest of the county – Abingdon more than Banbury, Witney more than Henley.

Nowhere is this more true than transport. The proposals, as yet, don’t advance any argument for fixing Oxford’s traffic even on its existing boundaries. Make the city bigger, and the problems grow with it. It’s not clear why Oxford’s population growth would be better accommodated at Wheatley (45 minutes from the city centre by bus) than Didcot (13 minutes by train) or Hanborough (9 minutes). “Closer” is best measured in minutes, not miles.

These are still early days for the proposals. The Government has asked for final bids to be submitted in November. Oxford City Council is inviting comments from residents between now and then. There’s a lot of time for any rough edges to be ironed out. Meanwhile, the rural districts are publishing a few more details about their own two-council proposal, and Oxfordshire County Council will unveil its own plans in due course.

Do you think of yourself as an Oxford resident, an Oxfordshire resident, or both? The answer could be very different in a few years’ time.

Further reading

- Official Greater Oxford site

- Our Housing Week series

- Our Infrastructure Week series

- Our primer on local government reorganisation