Oxfordshire’s councils: slicing the cheese

Do you want an extremely geeky deep-dive into local council reorganisation? You’re a Clarion reader. Of course you do.

Your quick recap. In those days, Angela Rayner issued a decree that county and district councils shall be merged. In previous episodes of the Clarion (cue dramatic theme music), we looked at the background, why Oxford City Council wants a Greater Oxford, and the case for a whole-county council. We wrote:

Local councils have been asked to draw up plans for these new authorities. Unsurprisingly, instead of digging their own graves, they have mostly responded with proposals to embiggen themselves while abolishing the others.

In other words, when the Government asked “We will ask you to work with other councils in your area to develop unitary proposals that are in the best interests of the whole area, rather than developing competing proposals”, Oxfordshire’s councils responded by developing competing proposals. These are:

- A single council for the whole of Oxfordshire (Oxfordshire County Council, unsurprisingly, supports this!)

- One council for the city and northern Oxfordshire; another council (‘Ridgeway’) for southern Oxfordshire and West Berkshire (the district councils, unsurprisingly, support this!)

- One council for an enlarged city (‘Greater Oxford’), one council for most of northern Oxfordshire, one council (‘Ridgeway’) for most of southern Oxfordshire and West Berkshire (Oxford City Council, unsurprisingly, supports this!)

The deadline for proposals to be submitted is 28 November. Government will make its decision in spring 2026, with elections to the new councils in 2027.

Inevitably, that decision will be (at least in part) political. It can’t not be. If the Government decides “we want councils that will help us build lots of houses”, it will make one choice. If it decides “we want councils that are cheap to run”, it might make another. Or it might decide “we want strong cities”, or “we’re taking aim at the Green Belt”, or even “we want councils with a fighting chance of being controlled by our own party”.

We can’t second-guess that. But we can at least look at some of the evidence they’ll be weighing up.

Population

Let’s start with the easy one!

The Government said it wants the new councils to have “a population of 500,000 or more”. We like that sort of clarity. “However, there may be exceptions to ensure new structures make sense for an area, including on devolution.” Ah, ok. “The population size of 500,000 or more is a guiding principle, not a target.” Hmm. “We understand that there should be flexibility, especially given our ambition to build out devolution and take account of housing growth.” Oh for…

So the new councils need to have 500,000 residents or more, except when they don’t. How do the proposals stack up?

- A single Oxfordshire unitary has a population of 738,000. Easy.

- A two-council split has one with 444,000 (northern/Oxford), another with 457,000 (Ridgeway). Close enough.

- A three-council split has Greater Oxford with 229,000, northern with 256,000, and Ridgeway with 414,000. Not really.

Ah, say Team Greater Oxford. But we’re going to build lots of houses. That will take us up to 345,000 (and northern Oxfordshire up to 340,000). Clever, hey?

Maybe. But Government wants more houses to be built everywhere, not just Oxford. If they meant “500,000 after you’ve built more houses”, surely they’d have said so? Or is this what “especially given our ambition to take account of housing growth” means?

Did we say this was the easy one?

Economy

If population were the only criteria, we’d just throw a computer at the problem and swap parishes in and out until each council hit 500,000. If that means Carterton ends up in Dorset, well, lucky Carterton. Sorry Henley, you’re part of Slough now.

Oxfordshire’s economy is thriving. We have top-flight universities, biotech, space industries, digital and AI, Minis, tourism, and cheese shops. But that economy isn’t evenly distributed. The space industry is clustered around Harwell and Culham. Oxford has three cheese shops, while West Oxfordshire has one and Cherwell, shockingly, none.

We've used per-district GDP figures (Gross Domestic Product) to work out the likely size of each council’s economy.

- A single Oxfordshire unitary would have a GDP of £31.5bn. Jeepers.

- A two-council split has £19.7bn in the north/City, £22.0bn in the south (Ridgeway). Closely balanced.

- A three-council split has £20.3bn in Ridgeway, £11.7bn in Greater Oxford, and £9.7bn in the north. Or if we put it in a chart:

Turns out West Berkshire is really prosperous! That might be thanks to Vodafone and AWE Aldermaston, or perhaps Newbury’s wine and cheese bar. But the corollary is that a three-way split would be unbalanced, with Ridgeway Council’s economy more than twice the size of the Cherwell/West Oxon combination. Yes, the north has its own industries and, in Blenheim Palace, Bicester Village, Soho Farmhouse and Jeremy Clarkson’s pub, a tidy tourist offer – but it’s no match for Science Vale or the University.

Does it matter? A healthy economy means a well-funded council – directly via business rates (currently divvied up between district and county councils and central Government), but also through the tax base of well-paid workers living locally. A solo Ridgeway would be sitting pretty. But would Banbury become the poor relation without Science Vale to support it?

(We’ve only looked at GDP here – essentially, council income. That’s just one side of the balance sheet. Cities and large towns have greater social housing (and homelessness) costs than rural areas. District councils tend to have healthy reserves (money in the bank), counties not so much. Government will want councils to be financially sustainable – but does that inevitably mean the bigger, the better?)

Politics

Here’s a quandary. Let’s say the Government is persuaded by the case for a Greater Oxford Council, which you might recall is “we’re only 229,000 right now, but we’re going to build lots of houses, taking us up to 345,000”. But then the electors of Oxford turn round and vote for a different party with the policy of “actually, we’re happy as we are, thanks”. Having set out a target size of 500,000, Government finds itself lumbered with a council of 250,000 residents.

Because that could happen. We’ve divvied up the most recent Oxfordshire election results between the councils, and added in (where appropriate) West Berkshire results adjusted to be equal-sized with Oxfordshire divisions. Here is how the votes would fall.

- A single Oxfordshire unitary would have a LibDem majority (36 LibDem, 12 Labour, 10 Conservative, 7 Green, 1 Reform, 1 IOA, 1 Henley, 1 Independent) – that is, the OCC balance of power as it is now.

- Under a two-council split:

- Ridgeway Council would have a LibDem majority (30 LibDem, 7 Conservative, 5 Green, 1 Labour or Independent, 1 Henley, 1 Reform)

- Northern/City would be a hung council with the LibDems as the largest party (16 LibDem, 12 Labour, 7 Conservative, 3 Green, 2 Independent). A minority LibDem/Green administration would have 19 seats from 40.

- Under a three-council split:

- Northern Oxfordshire would probably have a LibDem administration (12 LibDem, 7 Conservative, 5 Labour).

- Greater Oxford would be a hung council (7 LibDem, 7 Labour, 4 Green, 2 Independent, 1 Conservative). Any two out of the LibDems, Greens and Labour working together would have a majority, and recent precedent is for the LibDems and Greens.

- Ridgeway would be a clear LibDem majority (27 LibDem, 6 Conservative, 4 Green, 1 Labour or Independent, 1 Henley, 1 Reform).

The Liberal Democrats are flying high in Oxfordshire right now. One day, perhaps soon, the pendulum will swing the other way. But it’s remarkable that the most likely outcome for every single council is the LibDems in power, either alone or in coalition with the Greens.

Costs

“Disaggregation’s what you need… if you want to be a Record Breaker”

We can confidently say, with the assurance of Donald Rumsfeld’s known unknowns, that neither we nor anyone else have any idea how much all this will cost. Each council’s submission to Government will include some confident, plausible numbers. So did the HS2 business plan, which is currently orbiting somewhere around three times its initial estimate.

But we can at least say what the money will be spent on.

Disaggregation is splitting up existing County Council services between the new councils. Right now OCC has one adult social care department, one highway department. Moving to three councils would mean slicing these particular lumps of cheese three ways – a big reorganisation cost with no room for error (don’t even think about SEND pupils’ records being sent to the wrong council).

(Advocates of two or three councils will point out it’s a bit more complicated than this. West Berkshire is already a small unitary so has its own social care departments etc.; Oxford City Council does some highway work itself. There are other agreements that would need to be unpicked; for example, West Oxfordshire shares many of its services with councils in Gloucestershire. Our proposal for a Greater Cotswold Council has sadly gone unheard.)

Aggregation is merging existing District Council services, like planning and bins, into the new, larger councils. In theory this is easier and cheaper, because you can put it off indefinitely; there’s nothing to stop a single Oxfordshire Council having a ‘West Planning Office’, a ‘South Planning Office’ and so on. Some waste services are already run county-wide, and South and Vale have long been BFFs.

Consultants love citing savings from aggregation. We imagine the savings from moving TSB’s IT systems into those of new owner Sabadell, for example, looked very tempting. The ensuing chaos lasted eight months and TSB was fined £49m. Fortunately, public sector IT projects never go wrong at all ever.

Disruption, then. Sometimes, as with TSB, it hits the headlines. Usually it doesn’t. Yet reorganisation always means disruption and a loss of institutional memory. The sole 60-year old in Windrush District Council who understands planning issues in Little Sprotcot takes the opportunity for early retirement; the new, unified planning department glides smoothly on; then two years down the line, the Friends of Sprotcot Water Meadows haul the council to Judicial Review because a new development breaches an ancient covenant. There is a cost to this, most of which ends up on the Riviera via lawyers’ pay packets. But it won’t appear in the forecasts.

(To be fair, we should say that reorganisation can, sometimes, have an energising effect. Oxfordshire’s councils, no more or less than any other, can suffer from inertia and complacency. A new structure could shake that up. Your Clarion scribe has never worked anywhere where that’s actually happened, but we’re told it can.)

Ongoing costs are the headline act. Right now Oxfordshire has six planning departments (yes, OCC has one too!). One council means one planning department means big savings. Even the three-council plan implies a 50% saving. Repeat for Democratic Services (the people who run elections), backend functions like HR and IT, and the consultants are practically salivating.

Effectiveness

Running things better, then. Isn’t this why all this is happening? It makes no sense for one council in Banbury to approve 400 new houses, while another in Oxford has to figure out how the 1000 residents will get to work. The district council in Witney can blithely say “let’s expand Carterton as far as the A40”, while the county council is drastically paring down the A40 improvements to keep them under budget. Unitary councils fix this.

This increased efficiency and joined-up thinking should make for the biggest savings of all. But putting a number on it is destined to fail. Each business case will hand-on-heart argue that their proposal will work out best. Their proponents fervently believe it. They can’t all be right.

Here’s an example. Oxford City Council commissioned a survey about local government reorganisation, asking residents if they agreed with statements like “Councils are most effective when they are smaller and closer to the people they serve” and “Urban and rural areas often require different approaches”. 69.4% agreed with the first statement, 80.0% with the second. The City Council says this means “residents prefer smaller, more responsive councils”, like, purely for example, the three they propose.

The Clarion doesn’t have the budget for polling, but if we did, we could ask people if they agreed with statements like “Oxfordshire should have one council HR department, not five.” Or “It’s impossible to fix Oxford’s congestion without considering people driving in from the rest of the county.” Or if we were being really mischievous, “Abingdon [population 38,000, 7 miles from Carfax, not part of Greater Oxford] is more connected to Oxford’s economy than Weston-on-the-Green [population 500 and a dog, 10 miles from Carfax, part of Greater Oxford]”. We’re pretty confident those would get 80% agreement too. But their implication is the direct opposite of the City questions.

Perhaps we can find an impartial arbiter. Here’s a report that says unitary councils of 500,000 or more could save £1.8bn, while smaller ones would cost £850m in the same timeframe. That’s according to PwC, who were being paid by, er, the County Councils Network.

And here’s a report arguing that small unitary councils are best for children’s services. It’s written by the Staff College and funded by, wait for it, the District Councils Network. How about a report saying that cities are governed by outdated boundaries and need space to grow? That one was written by Inner Circle Consulting, paid for by ten smaller city councils (including Oxford, Cambridge, and bizarrely, Swindon cosplaying as a city). We haven’t yet found a report that argues local democracy is more harmonious when devolved to parish level, commissioned by Handforth Parish Council, but we’re sure it’s out there somewhere.

In truth, the big questions – transport, housing, democracy and responsiveness – are leaps of faith with all three proposals. Oxford City Council points to the success of its Oxford Model, where arms-length companies run services and generate income for the city, and says a Greater Oxford would free it up to build more houses and fix the city’s transport. It’s a heartfelt and persuasive argument.

But it’s not the only one. We’ve aired the idea of building houses near stations across the county, for example. New towns are being planned right now at Salt Cross, Heyford Park, Chalgrove Airfield and Dalton Barracks, all of them outside Greater Oxford. Pity the civil servants making the call on this one.

Identity and coherence

There’s one intangible we think we can take a stab at.

People want their councils to mean something. Humberside was established in 1974, bringing together East Yorkshire and North Lincolnshire. 20 years on, a local MP said that “almost the day after the decision was announced, a campaign began to have Humberside abolished”. They got their way in 1996. No one is campaigning to bring Humberside back.

Avon (Bristol, Bath and thereabouts) was equally unloved and was duly split. So too Hereford & Worcester, which reverted to separate Herefordshire and Worcestershire (though sadly not with the latter’s genuinely insane 19th century boundaries).

Oxfordshire is a universally understood area. So too is Oxford, and jokes about Weston-on-the-Green aside, surely Botley and even Kidlington villagers accept that their settlements are a little bit Oxford-ish.

The merged districts have to work harder. The two-council plan promises to “take advantage of the unique opportunities in each part of the county”. But it doesn’t explain why Oxford’s ‘unique opportunities’ are closer to those of Witney and Banbury than Abingdon or Wheatley. It talks of “looking further out from Oxford to key areas to the north, east and west”, but is silent as to why the south is shut out.

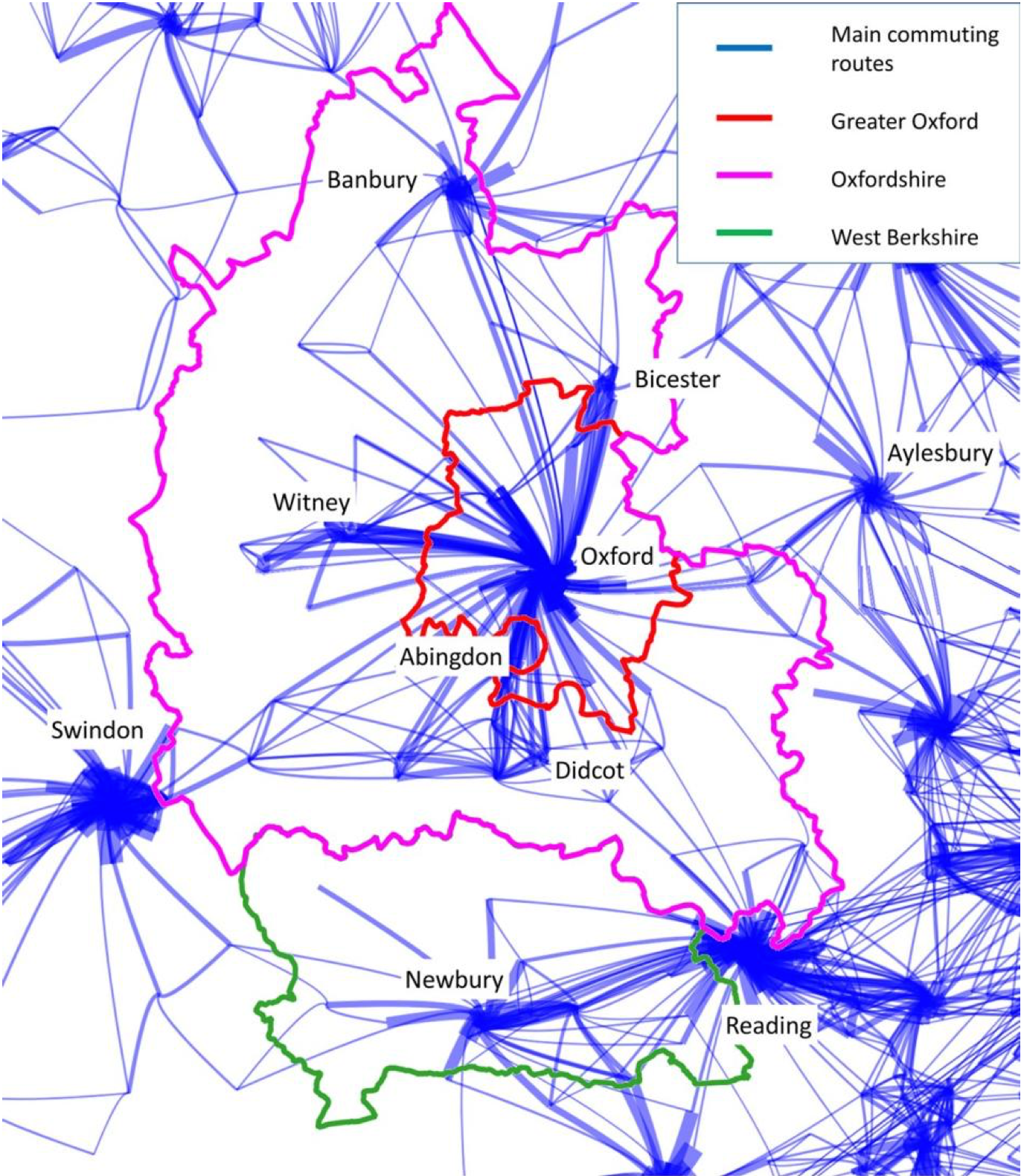

The Ridgeway concept has a lot going for it. It would be a coherent county of market towns and high-tech industry, of Thames and Downs, broadly homogenous and not dominated by any one settlement. There’s just one problem: West Berkshire people don’t actually travel to Oxfordshire, or vice versa. As this visualisation of travel-to-work patterns by think-tank POETS shows, West Berks looks to Reading (and Basingstoke, but let’s gloss over that), whereas Abingdon and Didcot look to Oxford.

Tough cheese

We recognise the Clarion is the Rest Home For Local Government Geeks in Oxfordshire, but even by our standards this is a tough gig. A dry subject, no easy answers, and – ultimately – a decision that will be made on national, not local, priorities. All over England, the same arguments are being had, and Government will at least seek to make its decisions consistent with each other.

It’s important; that’s why we write about it. Or maybe just because we want an excuse for some more cheese references. How would you slice the cheese? Let us know on Bluesky, Twitter, or at news@oxfordclarion.uk.

Footnotes

Links

Read the proposals for yourself! They have fewer cheese photos and more bloviating boosterism.

- Oxford City Council’s three-council proposal for a Greater Oxford.

- The rural districts’ two-council proposal.

- Oxfordshire County Council’s single council proposal.

Oxfordshire think-tank POETS is readying a report and you’ll be able to read it on their website. Oxford Civic Society is organising a public meeting on 1 November (booking required).

Data sources

Our calculations are based on LSOA (Lower-level Super Output Area) 2021 boundaries; population estimates per LSOA; and regional economic activity by GDP. LSOA boundaries do not exactly align with the proposed Greater Oxford council boundaries but we have taken an approach which we believe balances out overall. In some cases, more recent aggregate figures are available – Oxfordshire’s total 2025 population is closer to 770,000 than the 738,000 we’ve quoted – but the per-area proportions will remain broadly similar.

GDP figures are by district but, in reality, there will be some variance within the districts. In particular, we expect that the parts of Cherwell that Greater Oxford proposes to absorb (Begbroke, Kidlington etc.) have a higher GDP per head than the rest of the district, so you may want to adjust Greater Oxford’s projected GDP up slightly, and northern Oxfordshire’s down.

Special thanks to John Courouble for working up a set of figures that sense-checked our own calculations. Any mistakes are ours and ours alone.

What we haven’t covered

We’ve concentrated on the unitary council proposals and not the top-level ‘devolution agenda’, which will see an elected joint mayor for Oxfordshire, Berkshire, and who knows, maybe Buckinghamshire or Swindon. If we start writing about that we will get cross about how the Government is snatching defeat from the jaws of triumph by replacing one two-tier system with another. So we won’t.

We haven’t really looked at how you maintain grassroots accountability, and whether that should be through “local consultative forums” or via parish councils. Spoiler: it should absolutely, definitively not be via parish councils. Trust us on this one.